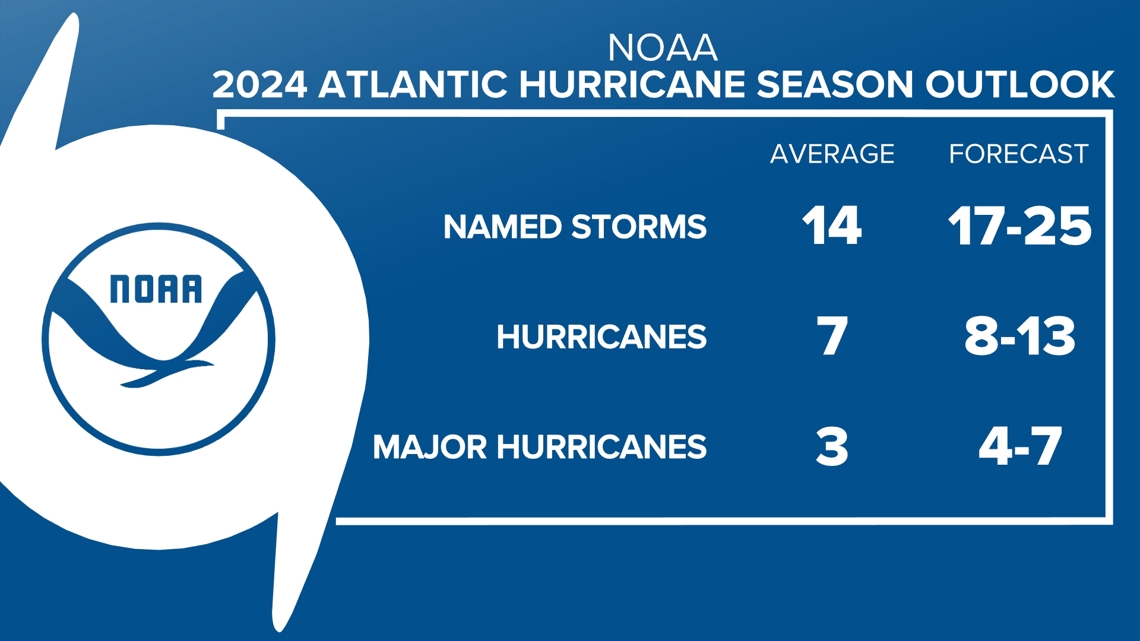

PORTLAND, Maine — Before the season even began, it was expected to be very active for Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Atlantic hurricane season outlook was calling for 17-25 named storms, 4-7 of which were expected to be major hurricanes.

The 2024 hurricane season kicked off with a record-breaking storm. Hurricane Beryl was the earliest Category 5 hurricane in the Atlantic Basin. That was followed up by Hurricanes Debby and Ernesto.

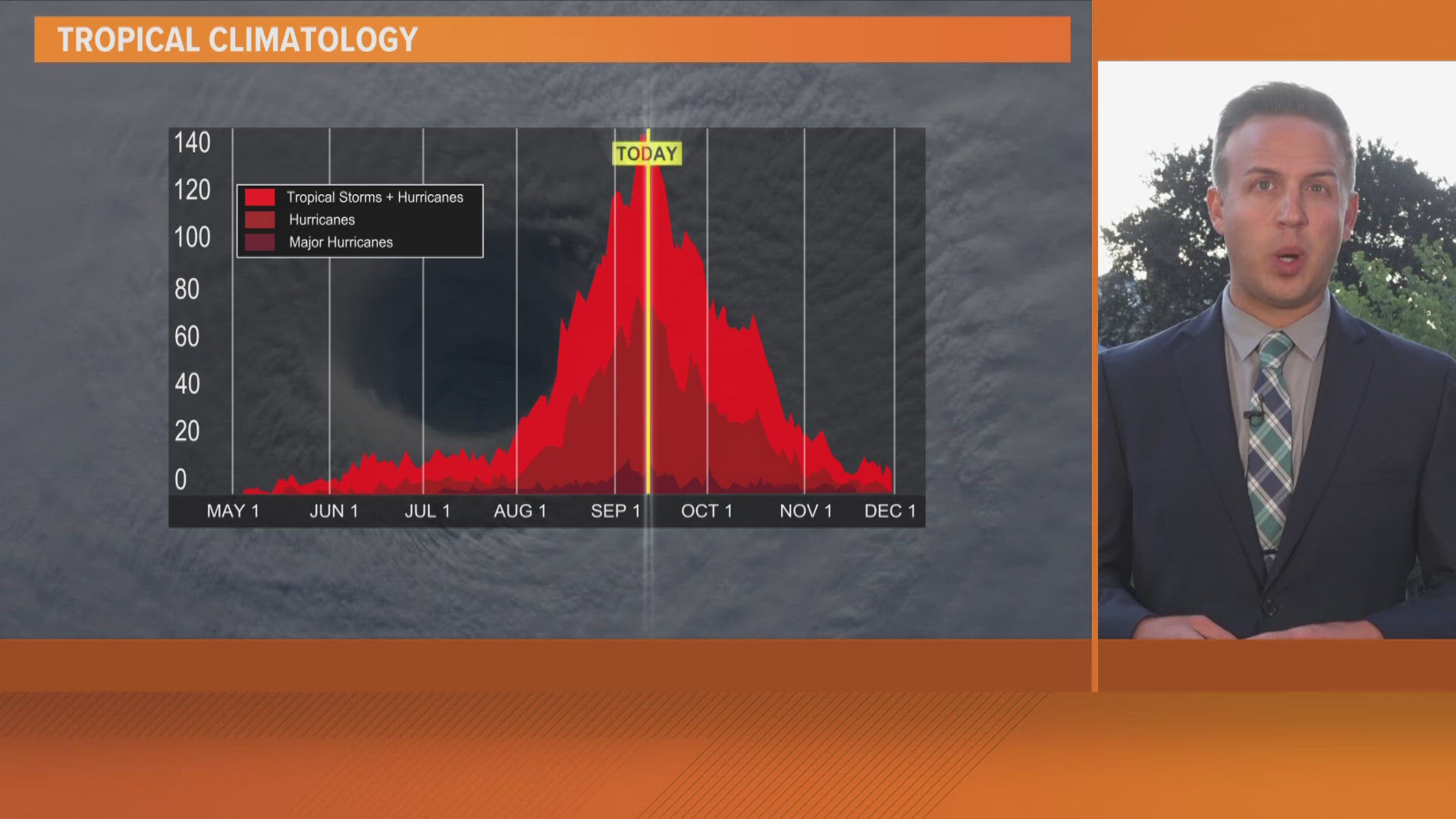

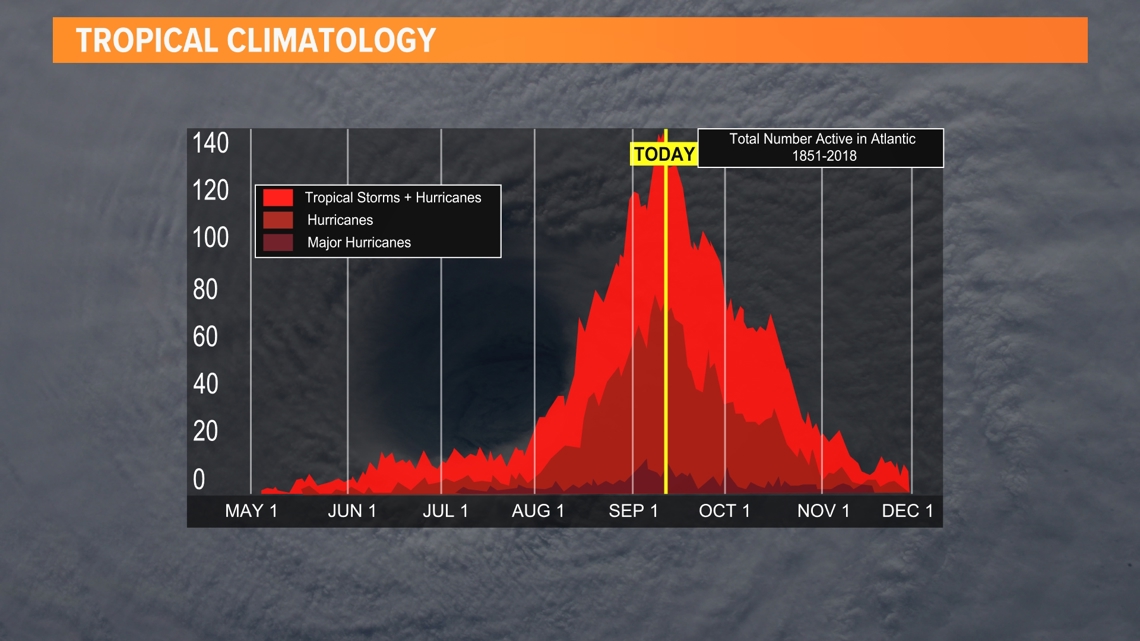

Fast forward to this week, the Atlantic hurricane season peaks, yet we’ve seen only five named storms to date.

Fewer destructive storms is a good thing, obviously, but why is this happening this season?

The slow hurricane season is due to several factors.

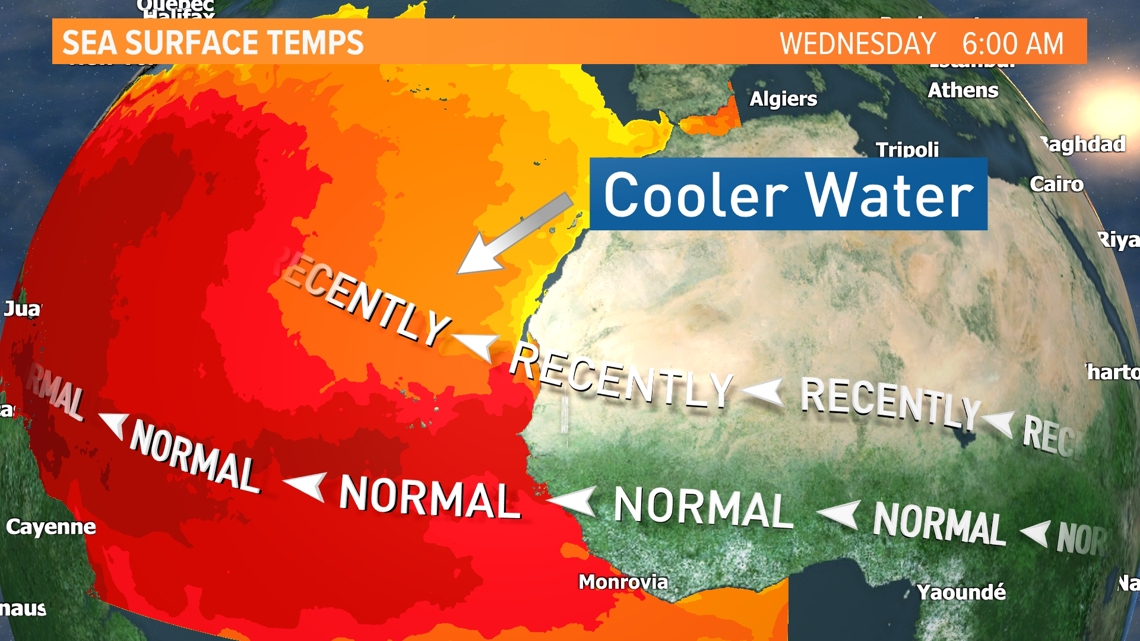

Textbook hurricanes typically come off the west coast of Africa near the Cape Verde Islands. This year, the monsoon track lingered farther north longer than average, which put these storms into an environment where waters are cooler and the air is drier. These conditions are much less favorable for tropical development.

Saharan dust is blocking solar radiation and depriving the environment of moisture.

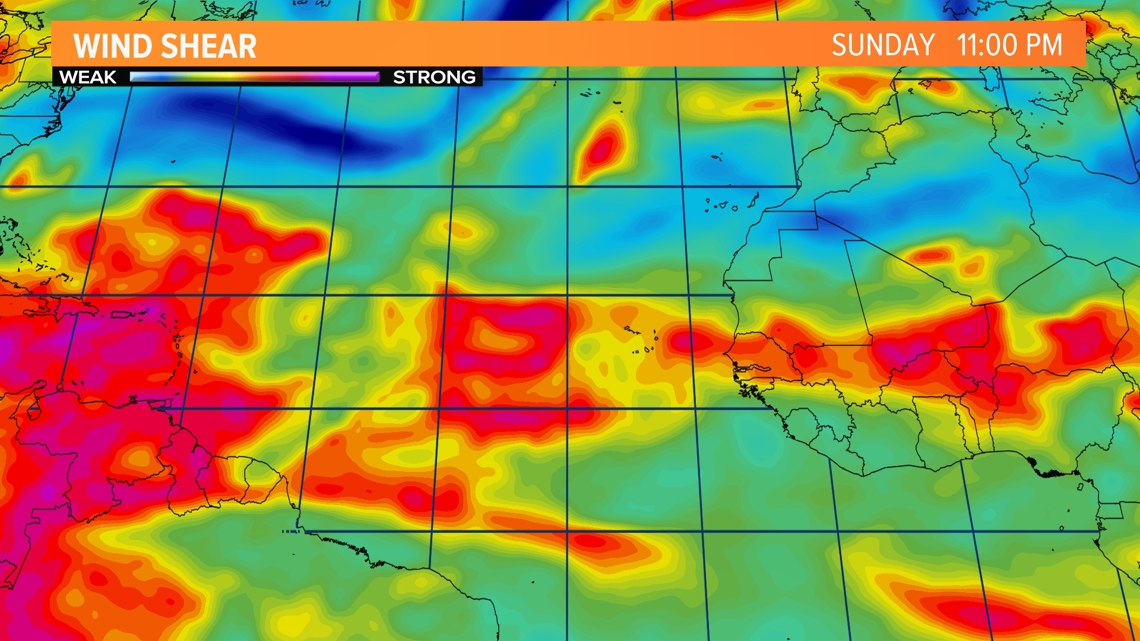

Increased wind shear disrupts hurricane formation and essentially tears hurricanes apart. We're expecting a transition to La Niña conditions in the coming months, which should reduce wind shear and promote hurricane development.

Lastly, warmer upper-level temperatures are stabilizing the atmosphere. For better hurricane development, we need warm air beneath colder air to create instability. According to an analysis from Colorado State University, climate change and El Niño conditions are likely contributing to this stabilization.

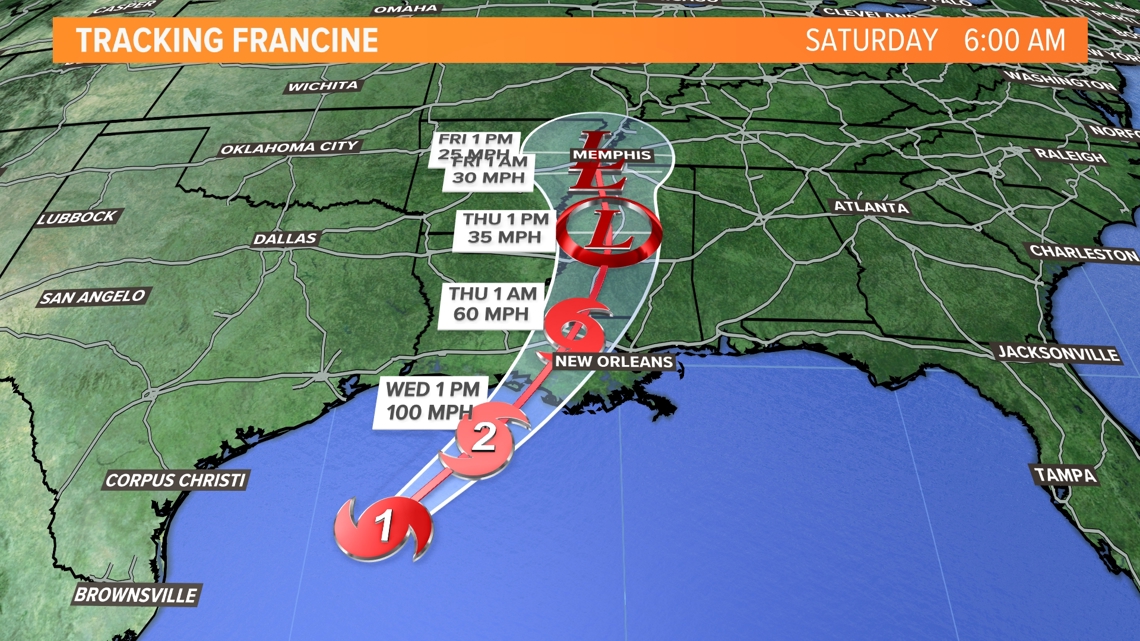

Hurricane Francine is already in the Gulf of Mexico as a Category 1 hurricane and is expected to make landfall in Louisiana later today as a Category 1 or Category 2 hurricane.