BONNEVILLE, Ore —

For all the impacts of other endangered species on the human communities they coexist with — owls and timber harvesting, wolves and ranching — there are few species that have affected more people than the decline of Pacific salmon.

And the people who have arguably been hit the hardest: the tribes of the Pacific Northwest.

“Salmon is really the heart of our culture. We're salmon people,” said Donella Miller, a citizen of Yakama Nation. “When we're born, we drink our mother's milk, but salmon was always our first food. That was the first solid food that I ate.”

Miller is also the fisheries science manager for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. She helps evaluate hatchery programs, oversees the commission’s genetics lab in Idaho and manages their river ecology projects.

The threats facing salmon aren’t any one thing — and that’s what makes them so vexing.

“It's a complex issue and you can't pinpoint one specific thing,” Miller said. “I refer to it as death by a thousand cuts.”

It’s hard to understate the importance of salmon to the Pacific Northwest. Chinook salmon is Oregon’s state fish and the west coast salmon fishery was worth more than $20 million last year, providing a cornerstone for coastal economies. They also play a crucial role in the ecosystems they reside in, transporting nutrients from the ocean to the headwaters of the streams where they spawn.

The species is woven into the very fabric of the region.

“It's extremely complex,” said Kim Kratz, assistant regional administrator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “There's too much at stake to allow these to continue to decline and to get disappointed and not invest in long-term recovery strategies.”

But to understand what threats salmon face, and how they might overcome them, you have to understand their life cycle.

A highly migratory species

Salmon are anadromous fish, meaning that over the course of their lives they transition from freshwater to the ocean and back to freshwater.

They begin their lives in inland rivers and streams, where they hatch and grow until its time to make their way out to sea. They spend anywhere between one and five years in the ocean before making their way back toward their spawning grounds, where they lay eggs before they die.

Over the course of their lives, a salmon will cross an untold number of boundaries, from rivers to estuaries to the ocean, from one state to another and sometimes across international borders.

It can sometimes feel like they face threats at almost every turn.

“Traditionally, we looked at the threats to salmon by the four Hs,” Kratz said. “There's habitat, there's harvest, there's hatcheries, and there's the hydro system.”

More recently, other predators like invasive fish species, sea lions and birds have been added to the list of threats.

“And then there's climate change,” Kratz said. “Climate change adds and increases their risk to all of those four Hs.”

While salmon face many threats, the hydropower system, and the dams that make it possible, stand out among them.

‘The water was cold, free flowing’

There are dozens of dams on the Columbia and Willamette river systems that help with flood control, provide for irrigation, facilitate navigation and generate low-cost, carbon-free electricity.

But dams also present physical barriers to salmon — both to young fish following the current out to the ocean and to older fish swimming upstream to their spawning grounds.

That’s where Tim Dykstra comes in. As the senior fish policy advisor for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency that oversees operations of the dams, he’s one of the people working to ensure as many salmon as possible get past the dams safely.

He said that infrastructure built into the dams on the Columbia River help older salmon return to their spawning grounds.

“Our fish ladders work very effectively and so that travel time and survival before and post dams is really for the most part unchanged,” he said, though he noted things are a little more difficult for young salmon heading in the other direction. “Dams have changed how juvenile fish do their out-migration from their spawning grounds to the ocean.”

Those fish not only need a strong current to lead them, they also must navigate through the hydropower turbines housed within the dams.

“We've installed major infrastructure upgrades, screens that divert fish from entering the turbines,” Dykstra said. “We've provided a lot of spill at the spillway at the dam, so that they have non-turbine routes to pass.”

Dykstra said those measures — the diversion screens and the increased flow of water over the spillway — have helped push juvenile salmon passage rates over 90%.

But dams do more than just present hurdles for salmon. They also fundamentally change how rivers operate.

“The hydro system does have major impacts and the overall changes to the system in general that affects all life stages,” Miller said. “You have flow, temperature, you have invasive species, predation and the altered environment that creates.”

Wilbur Slockish Jr., an elder with the Klickitat Band of Yakama Nation, said he remembers fishing at Celilo Falls, a thundering series of cascades on the Columbia River that used to be east of The Dalles.

“That's a sound that can't be replicated,” he said. “And the fish? There was plenty of fish all the time because the water was cold, free flowing.”

Celilo Falls was inundated when the dams were erected on the lower Columbia, swamping the fishing grounds and forming what is essentially a lake behind the dams.

“They flooded the spawning beds behind Bonneville Dam where our people fished,” Slockish said.

And that brings up one of the other Hs that salmon must deal with: habitat.

The habitat problem

Dams have cut off access to hundreds of miles of salmon habitat, but they aren’t the only thing blocking the fish from the areas they need to thrive.

"There's so much of the habitat that's been lost,” said Kratz. “And habitat is the foundation of the abundance of productivity, the viability of these species.”

On the coast, tidal estuaries have been converted to pastures. Further inland, vast wetland areas have been cut off from rivers.

The Palensky Wildlife Area, just north of Portland on the backwaters of the Willamette, is one of those areas.

A few years ago, it was 400 acres of disconnected habitat, parts of it cut off from the river for more than 100 years by culverts and water diversions.

Today, it resembles something closer to its natural state after a joint project between Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce and the Bonneville Power Administration gave it a major overhaul.

Culverts were removed and water diversion devices were replaced by natural woody structures that allow for fish passage. They dug channels to allow flood waters to connect wetlands. A large area was excavated to create marshlands that will help not only salmon, but migratory birds, amphibians and insects, too.

“So we're trying to restore processes, not just a specific one-size-fits-all habitat for some on it,” said Jason Karnezis, estuary lead for the Bonneville Power Administration’s wildlife program. “As a federal agency, you take the responsibility of recognizing the impacts that you have on the environment and you put that work on the ground as best you can, according to the science.”

Habitat restoration projects like the one north of Portland don’t necessarily yield immediate results, but Karnezis is confident that, eventually, they will play a crucial role in salmon recovery.

“You build it in year zero and it looks a certain way. Then, in year 10, you revisit it and it looks a different way and the fish response is different, and the vegetation is different,” he said. “We've documented those things over time and have found that the adage of ‘If you build it, they will come’ is true.”

There have been hundreds of similar habitat restoration projects completed throughout the Pacific Northwest. But there are other programs, initially implemented to help salmon, that haven’t always worked out as planned.

No silver bullet

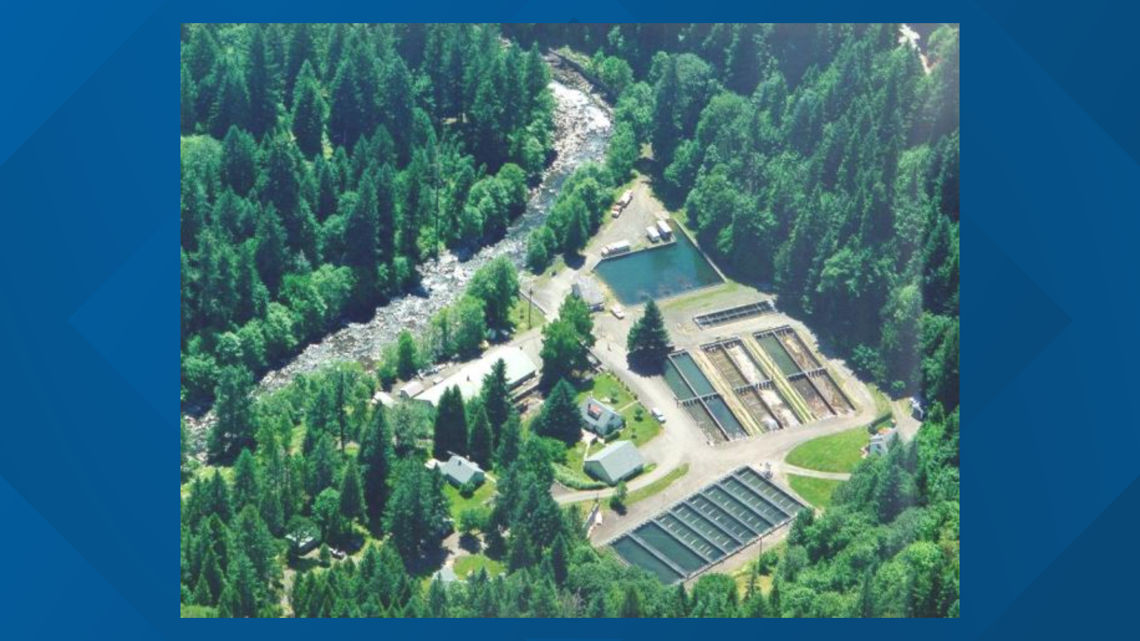

Since the late 1800s, people have been using salmon hatcheries to augment wild fish stocks.

“What hatcheries are intended to do is boost harvest opportunities, while at the same time reducing the risk to (Endangered Species Act) listed fish,” said Kratz.

But intent and reality don’t always align. Fish raised in hatcheries have proved inferior to their wild counterparts, mostly because of their genes.

“It seems like they're less able to respond to some of the threats that they've got because they have a more homogeneous set of DNA,” Kratz said.

And you don’t need to be a scientist to see the difference.

“The fish have gotten smaller since they put them into those little salmon reservations they call hatcheries,” Slockish said.

The real danger comes if hatchery fish breed with wild salmon, passing on their inferior genes in the process. Kratz said hatchery managers take great pains to make sure they time their releases to limit interactions between hatchery and wild fish.

But the idea that hatcheries could bring wild salmon back from the brink of extinction has proven false.

“It used to be that we thought that hatcheries were a direct replacement for declining fish populations,” Kratz said. “And now we realize that hatcheries provide an important benefit and they can be used for conservation, but they're not the silver bullet.”

Which brings up the last of the Hs: harvest.

Part of the Northwest fabric

With salmon facing so many threats at each stage of their lives, why are people still allowed to fish for them? Simply put, salmon are a big part of the region’s economy.

“These fisheries provide tens of thousands of jobs. There are hundreds of communities that are reliant for a resilient economy on these fisheries,” Kratz said.

But they’re more than that, too.

“They're part of the fabric of the West Coast region with respect to culture and the economy,” Kratz said. “With respect to the Indigenous people, they're inextricable from their culture, from their economy, from their art, from their ceremony.”

And that’s what makes the issue so personal for Miller.

“All of this is really emotional, emotional for me because it's part of who I am and my culture,” she said. “I see it as carrying on the work of my elders and my ancestors and setting the stage for our future generations to continue on this work to, you know, protect our environment.”

Despite all the threats facing salmon, there have been some signs of progress. Oregon coast Coho salmon and Hood Canal chum have shown promising signs of recovery. The biggest dam removal project in U.S. history — on the Klamath River in Northern California — is underway and will open hundreds of miles of salmon habitat once completed.

Still, Miller said that for all the good it’s done, the protections of the Endangered Species Act alone won’t be enough to save salmon.

“All of these species that were listed in the '90s in the Columbia River basin, how many of those have been restored?” she said. “I think it has the potential that it could be the most powerful tool that we have to protect species from extinction. But we've really yet to see the success of that.”

For Slockish, he knows he’s unlikely to ever see the salmon runs his ancestors did, but he hopes more people take lessons from the tribal perspective.

“We lived with nature, we know what it did and what it took to survive it,” he said “Now that's dominion. Not live with it, but tame it, make it come under control. That's why these dams are there. That's why we've got warm water. That's why we have less fish.”

This is the third chapter of "Endangered Northwest," a four-part series on the impact of the Endangered Species Act. Look for part four on Tuesday, which will take a broader look at the law and what it looks like today.

Part 1: The Northern spotted owl

Part 2: Reintroducing gray wolves

Part 3: Decline of Pacific salmon