FREEPORT, Maine — Editor's note: The attached video was originally published on Jan. 17, 2024.

Buying and selling Maine coastal real estate has long been about conveying the magic of living by the ocean. Increasingly, it’s also about prepping clients with the latest flood zone maps, projections for sea level rise and insurance availability.

These and other tools can give coastal home buyers critical information for making a risk-reward calculation about living on the edge — literally — in an era of strengthening storms fed by a changing climate.

With that new reality in mind, more than 100 real estate professionals packed a hotel conference room in Freeport on the last day of January for a presentation dubbed, “Living on the Edge.”

Periodic storms and flooding have always been a part of living on the Maine coast. But for some in the real estate business, the impacts of climate change may have seemed abstract and far off.

That changed, however, with historic flooding during the Dec. 18 wind and rain storm, and the back-to-back, record-breaking January storms that inundated the coast. Along with many buildings, they washed away the notion that a waterfront home is out of harm’s way, just because it has stood for a century or more.

Some takeaways from the presentation:

Coastal property owners should plan now for rising sea levels. Tides could come up on average 1.5 feet by 2050, and 3.9 feet by 2100, depending on future global emissions, according to the Maine Climate Council.

The trend already is compounding the impact of storm surge and storm tides, according to Peter Slovinsky, a marine geologist with the Maine Geological Survey. The Jan. 13 storm provided an illustration. Storm surge during an 11.2-foot monthly high tide in Portland pushed water to a record 14.57 feet.

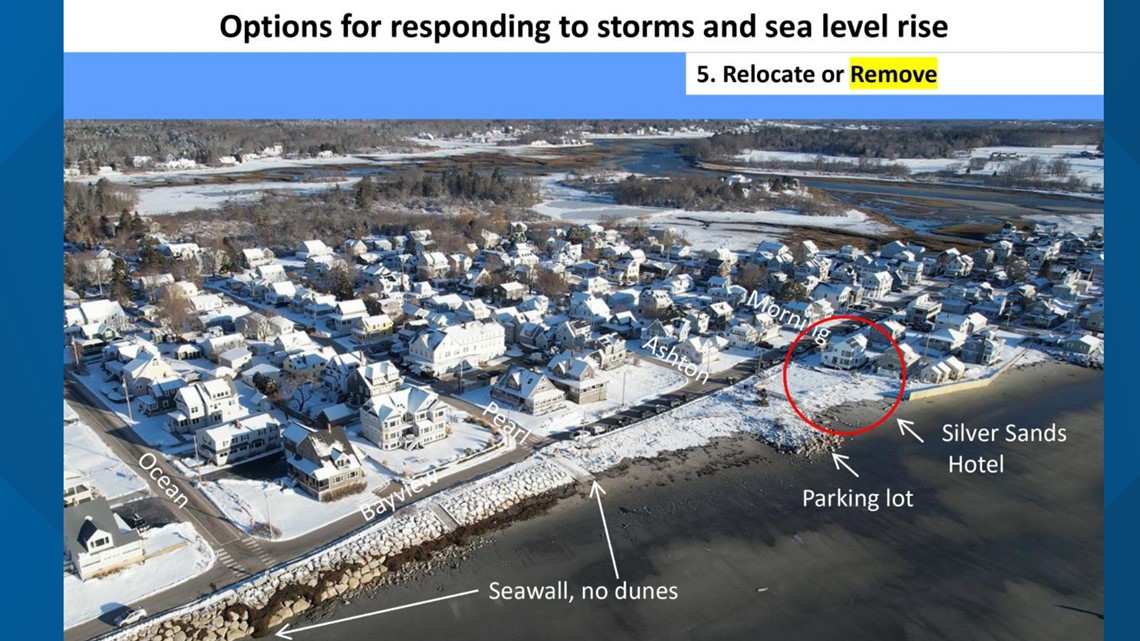

Maine has five options for responding, Slovinksy said. Property owners on higher ground may be able to do nothing. Avoiding new development in high-hazard areas is a second consideration.

Maintaining undeveloped vegetative buffers to provide space for future water levels, and elevating or setting back structures beyond minimum requirements, are ways to accommodate and adapt. Sand dune restoration and other nature-based solutions can help protect developed uplands, although they aren’t always effective against the worst storms.

As a last resort, Slovinsky said, buildings can be relocated, but sometimes they must be removed.

He showed slides of Higgins Beach in Scarborough when the historic Silver Sands hotel stood on the beach between the sea and Bayview Avenue. The hotel suffered severe damage and was torn down after a major winter storm in 1978.

Photos from last month show the hotel’s vacant lot, and a rock seawall now running where dunes had existed.

Hard decisions also are coming to property owners in Portland. The city is studying zoning changes aimed at making buildings and infrastructure more resilient.

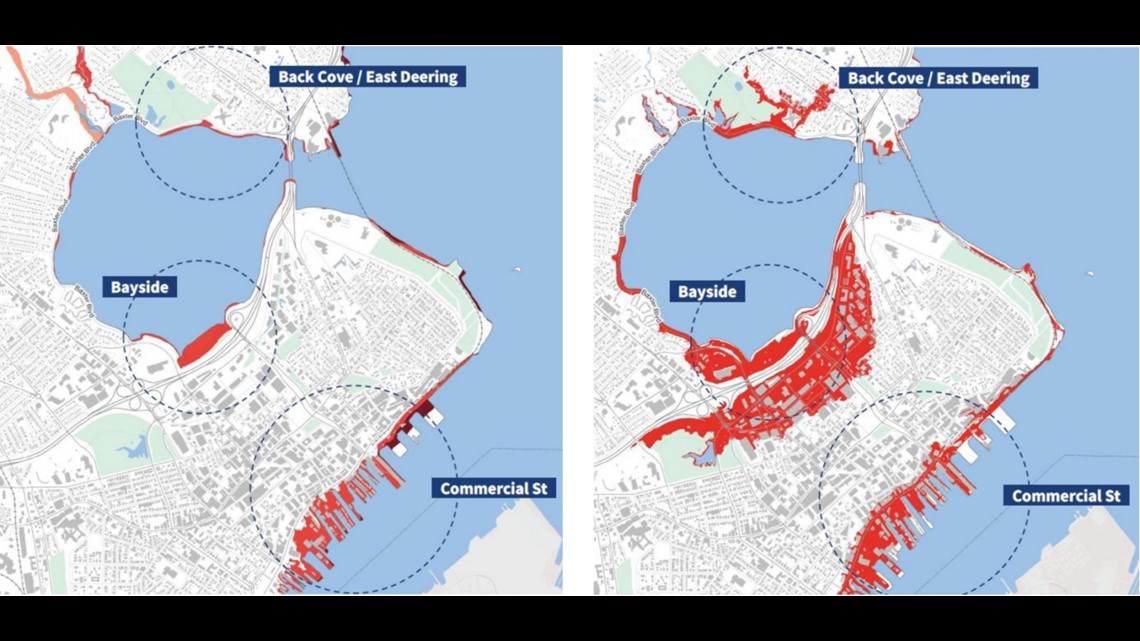

Current floodplain maps use historic data and don’t account for sea level rise. Troy Moon, the city’s sustainability director, displayed a map of Portland’s downtown peninsula with areas that would be underwater in a 100-year flood.

They mostly covered previously filled land around the margins of the harbor wharfs, Bayside and Back Cove.

But plugging in a new computer model using the state’s projected 3.9-foot sea level rise created an alarming map. Large sections of Bayside next to Interstate 295 were flooded, as was much of Commercial Street.

That’s a glimpse of the future.

Home buyers can get a sense of how vulnerable a property may be to storm damage by reviewing federal flood hazard maps. Revised FEMA maps for York and Cumberland counties will be available this summer, showing whether a home with a federally backed or insured mortgage needs mandatory flood insurance. Regular homeowners insurance doesn’t cover flooding.

But don’t count on a home being safe from flooding just because it’s outside a mapped flood zone, James Nadeau told the group. A Portland Realtor and land surveyor, Nadeau noted that 40% of flood claims over the past five years came from homes outside designated Special Hazard Flood Areas.

And don’t put much faith in Maine’s property disclosure paperwork that sellers fill out, Nadeau said. It gives a false sense of security because it doesn’t mention flooding, except to ask if the house is covered by flood insurance. It also provides an optional check-off for “unknown.”

Nadeau suggested home buyers can perform some of their own due diligence by typing the property address into the Climate Check website, which estimates storm, flood, and other weather risks based on 2050 national projections.

‘You can’t turn away from this’

Julia Bassett Schwerin couldn’t have anticipated the timing of these extreme weather events.

A certified Green and Smart Home broker in Cape Elizabeth, Schwerin began months ago preparing Living on the Edge, her fourth annual Sustainability Matters class, for professionals including agents, lenders, insurers, and builders. She co-chairs the Sustainability Advisory Group, a committee within the Greater Portland Board of Realtors. Past courses have covered topics including weatherization, electrification, and building energy codes.

Schwerin said she had long contemplated a workshop on the future of flooding in the Casco Bay region and its effects on waterfront property. She said she didn’t want to scare people, “but now felt like the time.”

Still, Schwerin couldn’t have guessed that the course would take place as Mainers continued to clean up from epic storm damage, a day after Gov. Janet Mills made storm preparation a highlight of her State of the State address and just as President Biden was approving federal disaster relief for 10 Maine counties.

As moderator, Schwerin also used the forum to draw a connection between threats to Maine’s tourism and coastal housing markets, and the burning of fossil fuels that is at the root of climate change.

“I was taking (the storms) as a positive wakeup call for people,” she said. “You can’t turn away from this. Everything we’re doing is bringing this on.”

Class participants heard from five experts on topics that included sea level projections, government flood insurance, revised flood maps, impacts on property values, and adapting for a future of rising water and stronger storms. (View the slide presentations.)

Inland owners also at risk

Coastal storms have done the most recent damage. But as December’s pelting rains demonstrated inland, rising rivers and streams can wreak havoc most anywhere in Maine. These events brought renewed attention to the value of insurance coverage, said Cale Pickford, an agent at Allen Insurance and Financial.

Homeowners can take steps to lower risk, he said. Make sure gutters are clear to handle heavy rain. Install water and freeze alarms to warn of catastrophic flooding potential.

Consider a whole-house generator to keep systems operating if the power goes out. But as financial losses mount, expect flood insurance rates to rise and underwriting guidelines in the private flood insurance market to tighten, Pickford said.

“Knowing the insurability of a property when buying a new home can be just as important as location,” he noted.

Even property owners who have flood insurance may find it doesn’t cover the contents of a building, or that the bar for proving water damage is higher than owners expect.

Does all this mean that property values are likely to fall in flood zones or areas with a history of flooding? Maybe, but maybe not, said Robert Lynch, senior vice president and chief appraiser at United Valuation Group in Scarborough.

As an exercise, Lynch studied 14 sales over the past three years at Camp Ellis in Saco, an oceanfront neighborhood long prone to flooding. He noted eight sales outside the current FEMA-mapped flood zone with a median sale price of $712,000. Six homes inside the flood zone sold for a median price of $593,750. That’s a nearly 17% difference.

But this group data analysis has flaws, Lynch explained. It’s a small sample. And it doesn’t account for the age, condition, or size of the homes.

A risk-reward calculation

Still, there’s evidence that the impact of climate change on home values is becoming part of the conversation.

One example is a recent blog from Rockland-based Cates Real Estate.

“January came in like a dragon,” it began, citing the unprecedented storm damage, an image of homes on a flooded street and a link to the state government’s assistance page. One of the brokers, Kerry Lee Hall of Scarborough, included a YouTube video of waves breaking over homes at Higgins Beach.

In a late-January article about home prices, a Cape Elizabeth real estate agent said she’ll be interested in seeing how coastal flooding will affect property values in her town and other coastal communities.

“The Cape has always been a desirable area,” Mary Libby told the Bangor Daily News, “but I think we’re going to have to watch what’s going on with the climate. I get calls from clients who are on the water saying, ‘What should we do?’ ”

The new reality may compel some buyers to revise their risk-reward calculations, according to Leanne Barschdorf Nichols, who started the Sustainability Advisory Group.

“It depends on how consumers perceive the risk,” she said. “People are going to have to make those decisions on an individual basis.”

A principal founder of the Keller Williams Realty franchise in Maine, Nichols said the recent storms make it imperative that real estate agents and clients talk frankly about the impacts of climate change. At the same time, she said she expects the market to adjust with mitigation strategies, such as raising structures or building farther back from the water.

“People cherish the waterfront in Maine,” she said. “They will find ways to adapt.”

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.