ORONO, Maine — Professors and graduate students at the University of Maine are pioneering ways to reduce damaging impacts from earthquakes known as "liquefaction."

That's when intense shaking from an earthquake turns the solid ground into something more like soup. Researchers are using natural bacteria already in the soil to try and stop this from occurring.

Seeing the aftermath of an earthquake of magnitude 7.5 followed by a tsunami that rocked parts of Indonesia in 2018, Aaron Gallant will never forget those images.

"We have seen this kill thousands of people. It's an acute event, and when it happens quickly, it's catastrophic," Gallant said seriously.

Gallant, an associate professor of geotechnical engineering at the University of Maine, visited Indonesia with a team of experts to gather data and understand the impact of extreme events better. The team’s report was published by the Geotechnical Extreme Events Recognizance Association, which organized the team.

Gallant traveled to Oregon to work with researchers from Portland State University on a new method to fortify earthquake-prone soil. The region faces a potential nightmare scenario unless work is done to stabilize the state's main fuel storage facility against a major earthquake, which will come sooner or later.

Diane Moug is a civil and environmental engineering professor at Portland State University.

"The earthquake will occur. We don't know exactly when, but it will occur," Moug said matter-of-factly.

As part of the project, researchers are injecting nitrogen-rich compounds into wells at the test site near Portland's airport.

"What we are doing is feeding the microbes nutrients, which accelerates the nitrification process that generates the gas," Gallant explained.

This gas-filled soil acts like a shock absorber, resulting in a lower risk of liquefaction when shaking during an earthquake causes the ground to liquefy.

Teams from both universities are utilizing nearly $1 million from the National Science Foundation to see if the new method could be a solution to protecting critical infrastructure. Gallant is working on the project with Luis Zambrano, an assistant civil and environmental engineering professor at UMaine.

"We are attacking it here at UMaine by trying to understand how long the gas will be there," Gallant added.

Zambrano will analyze data collected from the site. The research is also personal for him, as he lost many friends following a major earthquake in his native Ecuador in 2016.

"That key infrastructure we need to ensure it will be functioning in a disaster like this," Zambrano said.

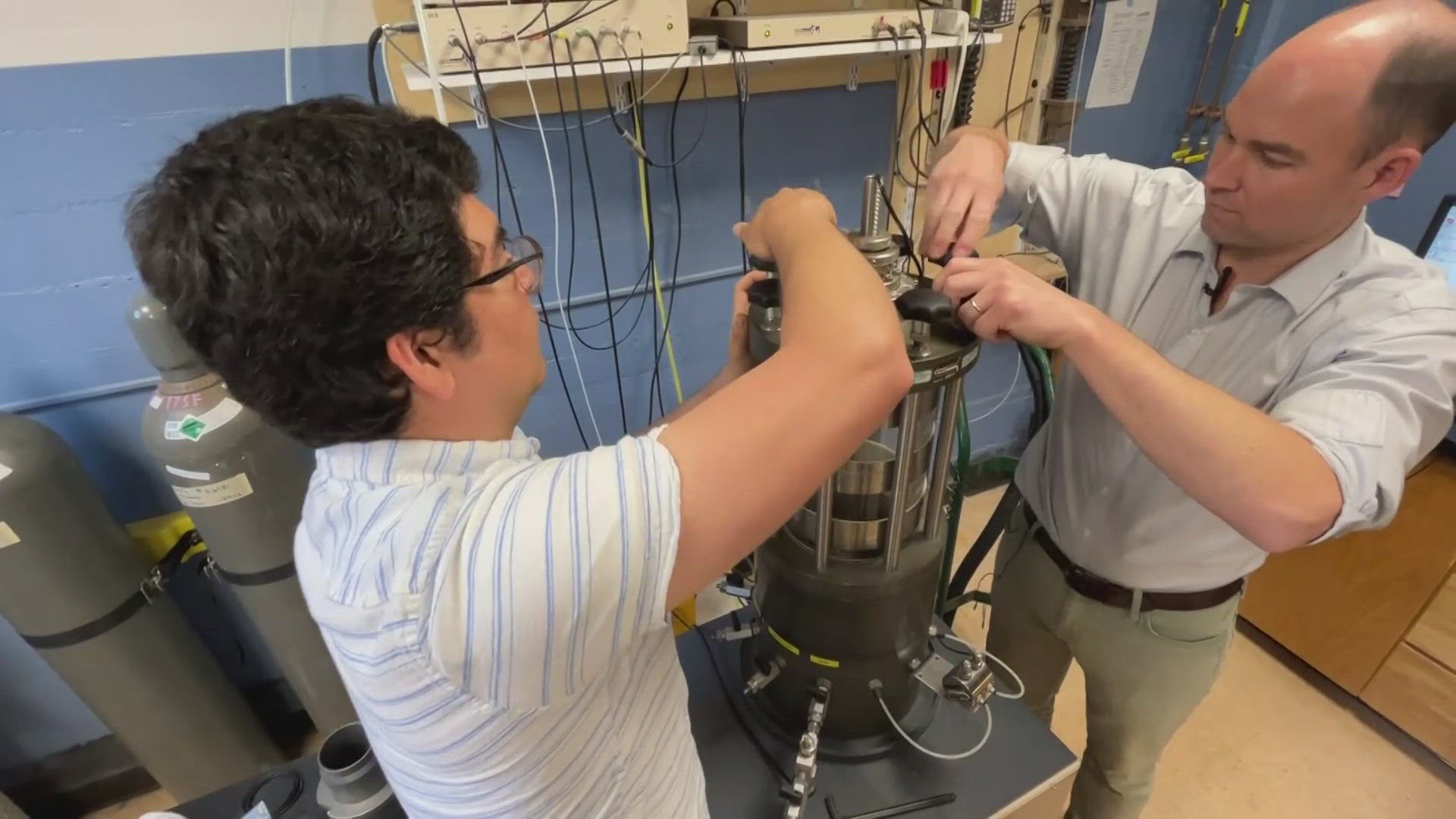

Upon returning to Maine, scientists will be testing soil samples from Oregon using a pressurized machine that can simulate an earthquake.

"We can vary the applied conditions to simulate different earthquake magnitudes," Gallant explained.

The goal is to buffer vulnerable areas against earthquakes and make the method cost-effective and accessible worldwide in the next five to 10 years.

"This type of method could be applied under an existing building, existing structure, or fuel tanks," Moug explained.