MAINE, USA — At a paper mill warehouse near the University of Maine, engineer Ian Toal oversees a huge, intricate machine that turns sawdust into a key ingredient for a new kind of heating oil.

Researchers at this pilot-scale plant in Old Town, part of UMaine’s Forest Bioproducts Research Institute, have spent years developing alternatives to fossil fuels by using wood that might otherwise go to waste.

The goal, Toal said, is to fight climate change by working toward replacing oil with a “renewable fuel source” — renewable because unlike coal and oil mined from underground, trees regrow over decades. This eventually helps offset the carbon they emit when burned.

“I’ve got a 5-year-old at home that I still can’t imagine what kind of world he’s going to grow up in,” said Toal, wearing a dusty white lab coat and safety goggles while giving a tour of the biofuel plant in late May. “Anything I can do to help make that a world close to what we’re living in, or a better world, is motivation for me.”

As residents consider their high oil costs from this past winter and plan investments for the future, wood heat is an increasingly attractive option, with complex climate change implications.

Many climate scientists disagree with the claim that burning wood for energy, as opposed to fossil fuels, has an advantage in slowing the climate crisis. It’s a controversial strategy that hinges on a lot of tricky assumptions about forest management, timelines, and more.

This debate is especially important in Maine, the most heavily forested state and, as The Monitor reported in this series, the one most heavily reliant on dirty, expensive oil for home heating.

Because trees are made of carbon, Maine’s expansive forests are a huge storage bank for carbon emissions that would otherwise warm the planet.

Though state policymakers see some value in wood energy as Maine works toward its climate goals, their focus for decarbonizing home heat is on weatherization and electric heat pumps.

But Maine’s vast forests also make wood heat cheap and widely available. And oil distributors are already touting a transformative new invention in the liquid wood-based fuel that’s in development in Old Town.

A familiar local heat source

Certain forms of wood heat are already common in Maine. Wood pellets and cordwood used in home fireplaces and furnaces are the cheapest heat options for most residents.

Mainers get more actual units of heat from these wood products than from any fuel besides oil, according to state and federal data — and wood use tends to rise when oil prices spike, as they did late last year.

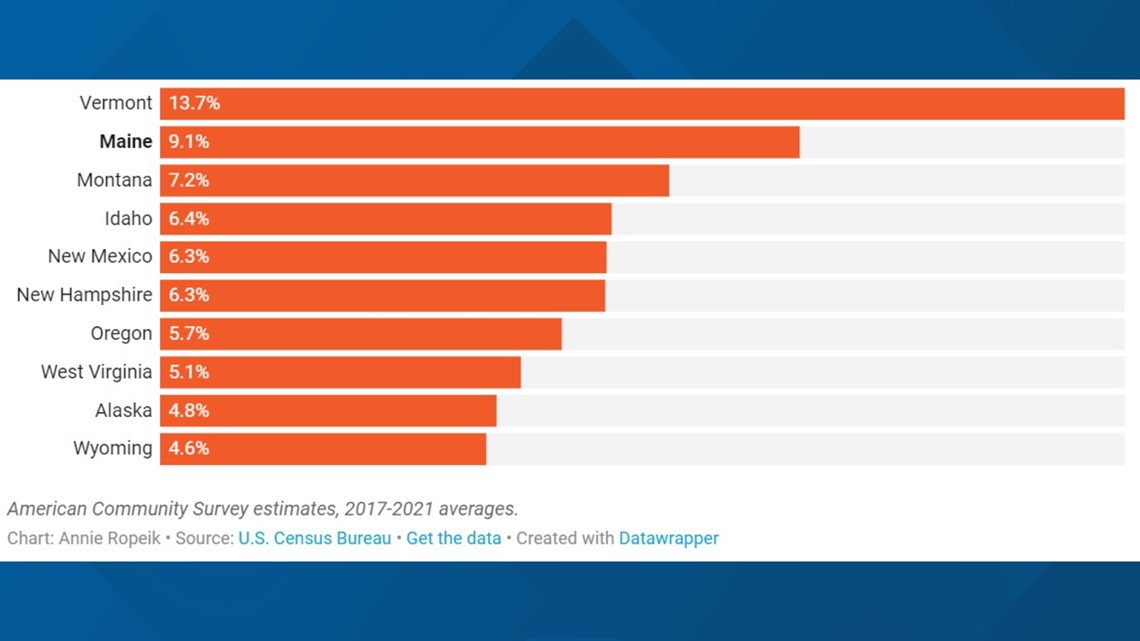

Which states have the highest proportion of households using some form of wood heat?

Efficiency Maine offers up to $6,000 off the cost of certain central-heating furnaces or boilers that burn pellets or cordwood, described on the rebate provider’s website as “a local, renewable fuel.”

Cordwood cut from backyards and by timber companies is everywhere in Maine, while pellet systems run on a fuel mostly made in Maine with compressed sawdust from local mills and other kinds of “waste wood.”

Scott Nichols owns New Hampshire-based Tarm Biomass, which sells pellet furnaces and other wood heating equipment. He sees wood as an ideal part of homeowners’ home heating strategy, which can also include electric heat pumps.

“We ought to be eliminating fossil fuels at every chance we have, and if we have a local resource like wood that’s also providing a local economic benefit, it seems like a smart choice,” he said. “And maybe in 30 years or whenever, when we have some form of non-combustion technology that can replace the benefits that wood provides, then that’s great — but right now we’re nowhere near what we need.”

Nichols said these wood heat sources are so consistently cheap in Maine for two reasons — abundant local wood supply, and because they have to be low-cost to compete with the convenience and availability of oil and propane.

Bill Bell, the executive director of the Maine Pellet Fuels Association, said he saw this dynamic when oil prices dropped in the 2010s and pellet adoption slowed. When fossil fuels are an easy choice, he said, it’s harder to convince people to make a switch.

“Our basic competitor is inertia,” Bell said. “The (time) that’s important for us is right now, when people have gone through a winter and have the time to think rationally about, ‘You know, we paid an awful lot for oil or propane, and we should be thinking about making a change, maybe.’ “

Plant-based alternatives

Certain oil distributors are exploring something very different from pellets or cordwood. They’re working on converting wood and other plants to liquid biofuels, named because they’re made of living material. You’ve used a biofuel before if you’ve bought gasoline mixed with corn-based ethanol (perhaps called E10 or E15, with numbers referring to the percent of ethanol mixed in).

The heating industry is developing its own biofuels, and mixtures of biofuel and fossil oil, they say could nearly directly replace the heating oil homeowners have delivered to their tanks several times during the winter.

These fuels are designed to “drop in” to residents’ existing heating systems with low-effort, low-cost retrofits, and upgrades — such as additives to keep the new fuel flowing in cold temperatures, or gaskets and seals made of materials designed to work better with biofuels.

Advocates say these liquid fuels can be handled by existing oil workers, trucks, and other infrastructure.

“As I talk to folks in the industry … they’re kind of anxious for this to happen,” said Tom Butcher, the technical director for the National Oilheat Research Alliance. “They want to demonstrate that they can be part of a low-carbon future.”

Butcher’s group, known as NORA, was created through an act of Congress in 2000 to study efficiency and safety improvements for oil heating. It’s funded by a small fee on heating oil sales, like the checkoff programs that exist for farm commodities.

At a Northeast oil heat industry conference in 2019, NORA and other groups pledged to go carbon-neutral by 2050. Their near-term focus is on farm crops and food waste, not wood — they’re rolling out blends of regular oil with increasing mix-ins of biofuels made from plants like soy, canola, and corn, plus used cooking oil and other waste feedstocks.

Toal, the UMaine plant manager, uses heating oil with a 20% add-in of plant-based biofuel at his home in Freeport. Mixtures of oil with 5% or 20% biofuel are already for sale by many oil companies in New England, said Butcher, with 50% and 100% options in the works.

Toal said using this lower-cost biofuel mix-in helped ease the impact of fossil oil’s price spikes this past season, especially combined with his home’s heat pump and rooftop solar panels.

Wood-based liquid EL heating fuel

Toal looks forward to the day he can make a major upgrade — entirely replacing his heating oil blend with the wood-based fuel he’s studying. It’s known as ethyl levulinate, or EL.

The process that Toal is testing in Old Town runs sawdust from a nearby mill or waste cardboard through a series of chemical reactions. By adding steam and a little sulfuric acid, the process concentrates and converts the wood’s carbon content into several useful products — including levulinic acid, the key ingredient used to make EL.

EL is not on the market yet, but Biofine Developments Northeast, UMaine’s private partner at the pilot plant, is building its first commercial-scale EL factory in Lincoln. It aims to be operating by early 2026.

Steve Fitzpatrick, the Biofine founder and CEO, said the fuel he pioneered burns efficiently and with 35% lower particulate emissions than ultra-low sulfur diesel, which is equivalent to heating oil.

Asked about the fuel’s expected cost, Fitzpatrick said, “With established federal tax incentives for renewable fuels, EL can be sold competitively into the heating oil (market).” Biofine signed an agreement in 2020 to sell EL with Sprague Energy, a major Northeast oil distributor.

Ryan Rogers, a general manager for the heating fuels company Dead River in Presque Isle, is a longtime EL evangelist who has tested it in his own home and spent years researching the small heating equipment changes needed to help bring it to market.

“The talk around climate change has kind of put an expiration date on the (oil) industry that I’ve started in,” Rogers said. “What I really hope is to have people aware … that we can make a product that can power our economy, made from local sources.”

An abundant waste resource

To qualify for federal renewable fuel subsidies, the Biofine plant will primarily have to make its product with what’s known as “slash” — the woody debris left behind from harvesting whole trees for other higher-value uses, like lumber and paper products — and “pre-commercial thinnings,” which are smaller trees culled out of the forest as part of routine management.

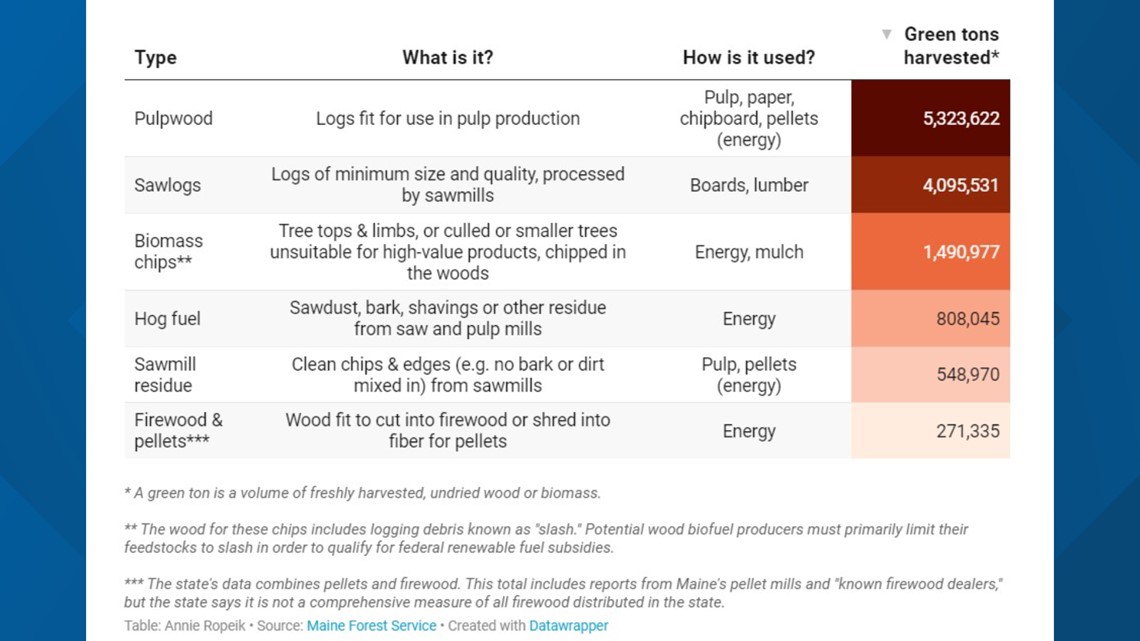

Wood products & waste harvested from Maine forests, 2020

The timber and scrap wood harvested from Maine's extensive forests goes to a wide range of uses -- from lumber, pulp, and paper, to pellets for home heating or woodchips for electricity production. Here's the most recent available state data on how this harvest breaks down.

The goal of these standards is to ensure that most of the wood in the forest continues to store its carbon, keeping it from entering the atmosphere.

Maine’s vast forestlands are what’s known as a carbon sink — a crucial one. A 2022 state report showed these forests already sequester most of Maine’s carbon emissions, which come mostly from transportation and home heating.

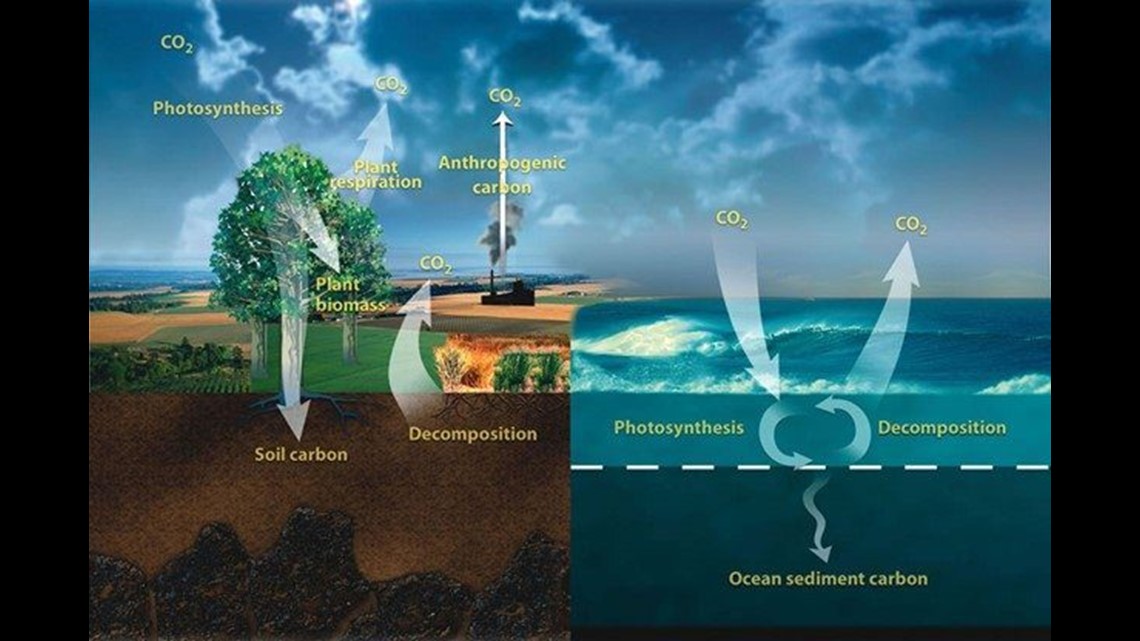

Trees and plants breathe carbon dioxide, adding that carbon onto their bodies as they grow — and holding onto it, even when they’re cut down and made into wood or paper. They emit their carbon if they’re allowed to decompose or if they’re burned.

Because Maine’s forests are mostly privately owned, timber industry advocates argue the landowners need a range of ways to make money off of keeping their forests as forests, rather than selling the land for development into, for example, housing. A 2017 Harvard Forest report said New England is actively losing forest acreage to development as conservation efforts slow.

Wood heat advocates also argue that waste wood, eyed for energy uses like biofuels, would otherwise rot on the forest floor or in piles outside sawmills, creating wildfire risks and emitting its carbon sooner or later as it decomposed.

“You’re replacing fossil fuel that doesn’t have a renewable source … by tapping into that natural cycle of wood growth and death and rotting,” said Fitzpatrick.

At the outset, the Lincoln plant will use roughly 70,000 “green tons” of waste wood from the surrounding area to make 3 million gallons of fuel a year. In theory, that could replace 1.4% of the 213 million gallons of home heating oil sold to Mainers in 2020, according to federal data.

By expanding production in Lincoln and building plants at other former pulp and paper mill sites, where nearby wood supplies are already assured, Fitzpatrick said Biofine’s output could rise “into the hundreds of millions of gallons, literally, within probably 10 years, or maybe less.”

“Once we get that first commercial plant running … I hope it doesn’t give people the wrong impression, but I say you can’t build these plants fast enough,” he said. “I think the demand will be huge. I think it will do the state and maybe the Northeast as well a world of good.”

Fears about intensive harvesting

Waste wood is especially abundant in Maine in part because it’s become less used by electric power plants that burn it to supply the regional power grid. These biomass plants have struggled economically across Maine and New Hampshire in recent years, and many have closed.

But wood heat opponents fear that growth in the wood heating industry could lead to the burning of whole trees for energy use — removing much more carbon from the forest and, in turn, accelerating climate change.

These concerns have come true in the wood pellet energy sector. An investigation by the nonprofit news outlet Mongabay last year showed that a major company in the Southeastern U.S., counter to claims about focusing on waste wood, is clear-cutting forests and using whole trees to make pellets. These are exported to the U.K. and Europe, where they’re considered a key, heavily used renewable fuel for electricity production.

“We just don’t have that” in New England, said Eric Kingsley, a Portland-based forest products consultant. “We’re operating in clear synergy with the existing forest products industry, and we’re meeting a local need, not a British or European need.”

While waste wood is preferred for making both pellets and the biofuel Biofine is developing, there are other potential inputs. If Biofine ran low on waste wood sources, chief development officer Mike Cassata said, they’d supplement what they use to make their fuel with waste paper and cardboard from garbage.

“It would make no sense for us to use whole trees rather than municipal solid waste,” Cassata said. “The whole tree doesn’t qualify for (the federal subsidy); it’s not as beneficial from a carbon sequestration standpoint. It’s not something we’re really interested in looking at.”

Carbon neutrality is not climate neutrality

No matter the type of wood used to make energy products, it still emits carbon when burned. In fact, wood emits more carbon per unit of heat than oil or coal due to its moisture content.

Biofine considers EL to be carbon neutral because waste wood left in the forest would decompose and release its carbon within years on its own, and because trees regrow, storing new carbon that eventually cancels out the emissions from burning the fuel.

In fact, Biofine said EL actually emits less carbon than what was contained in the wood used to make it. One byproduct of the refining process, biochar, is being evaluated as a useful fertilizer or soil additive that retains its carbon content “almost indefinitely,” Fitzpatrick said.

But some scientists who oppose a shift to wood-based energy dispute this rosy perspective.

“Carbon neutrality, which is what the industry focuses on, is not going to bring about climate neutrality,” said John Sterman, a professor of system dynamics at MIT who helps run a widely used climate solutions simulator called En-ROADS. This data platform shows that using more bioenergy for heat or power would generally increase, not decrease, global temperatures.

The key problem, Sterman said, is in the timeline. When wood is burned, it emits carbon into the atmosphere, where that carbon warms up the earth. Meanwhile, new trees are growing, breathing in carbon and adding it onto their mass.

But even when those new trees have absorbed the same amount of carbon as was originally emitted by burning wood, it doesn’t undo the warming effects that took place in the meantime.

“That means all during that period, and after … you have a warmer planet,” Sterman said. “You’re going to have higher sea levels, you’re going to have more extreme weather, you’re going to have lower crop yields, you’re going to have more people dying from excess heat, and none of those effects magically go away just because the atmospheric CO2 would stop rising.”

Sterman’s preferred heating oil alternative is the same one Maine has prioritized in its climate plans — intensive home weatherization to lower energy use altogether, and efficient electric heat pumps, which don’t emit their own carbon and run on an increasingly clean grid.

Maine’s oil distributors have been linked to campaigns against heat pumps. Many wood heat proponents argue they favor an all-of-the-above approach — in line with many Mainers’ traditional use of a wood stove as a backup fuel source that doesn’t rely on electricity.

“There is a place for biofuels and wood heat — it’s just not a no-emissions solution,” said Hannah Pingree, the Maine Climate Council chair. “So it can’t be kind of the primary focus.”

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.