FALMOUTH, Maine — On a small salt marsh, near the mouth of the Presumpscot River, Doug Hitchcox kneels and spreads apart some of the coarse marsh grass.

He’s a naturalist with Maine Audubon and is showing us where the small Saltmarsh sparrows build nests, and why their future in Maine may be bleak because of a changing climate.

“I always love saying why should we care about the Saltmarsh sparrow,” Hitchcox said.

The answer always pleases people because these sparrows love to eat greenhead flies, which often annoy humans with their nasty bites.

But Maine’s Saltmarsh sparrow is at risk. As the climate warms and sea levels rise the marshes will no longer provide a safe habitat for sparrow nests, Hitchcox said.

If sparrows lay their eggs in those nests on the ground of the marsh, and the regular tides are washing in higher and higher inundating those nests, reproduction will drop. And with populations of the Saltmarsh sparrow already in decline, he says the future doesn’t look good.

“Unfortunately, without a true conservation effort, it’s a species that will likely go extinct in our lifetime, given the trends we see," Hitchcox said.

Perhaps nothing brings life to the landscape as much as birds. Their songs, their calls, their color and variety, and the sheer spectacle of their flight all make birds a prized part of the landscape for people.

So the loss or significant reduction of a bird species like the Saltmarsh sparrow will certainly be noticed. But the very same climate change that brings about the demise of the Saltmarsh sparrow will trigger changes to benefit other shorebirds. For example, the more frequently flooded marshes will become more plentiful food sources for other shorebirds.

And some birds can be remarkably resilient. Evidence of that includes the recovery of the bald eagle, which has been significant in Maine.

Added to that, birds will permanently move with their habitat. In other words, if the warming climate in Maine causes a bird's habitat to change, those birds will move north to cooler climates, like Maine used to be. One, the boreal chickadee, is "moving northward and moving out of some areas they've traditionally been in, like Downeast Maine," Hitchcox said.

As recently as last spring, a bird spotting trip showed very few boreal chickadees in places where they were once common. And worst of all, perhaps, one of Maine’s most beloved birds is also threatened.

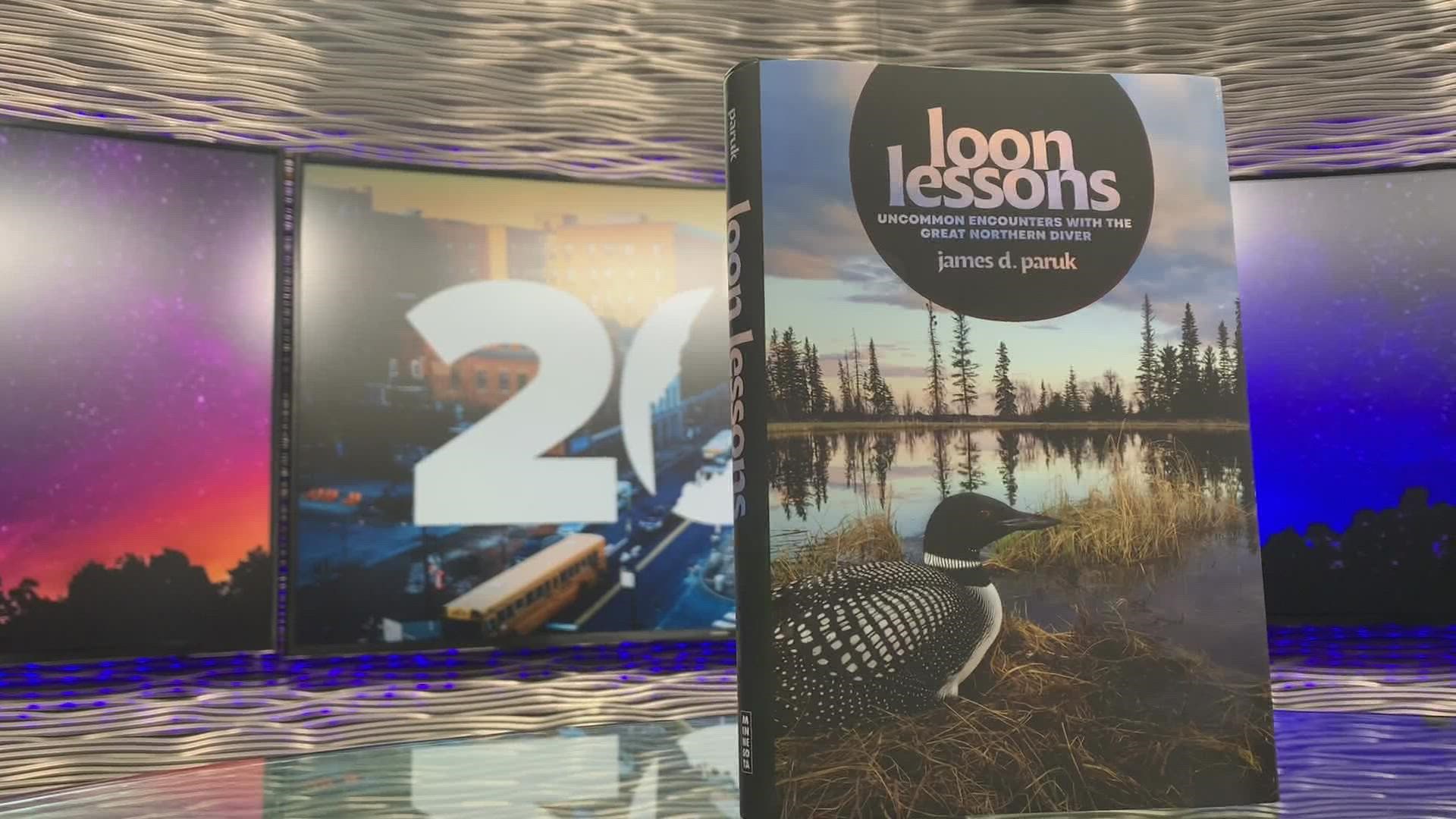

“Our most iconic species," said Hitchcox. "We might lose the common loon. To think that other-worldly yodeling call you hear on Maine lakes in the summer, to think that could be gone in the next 50 years, as they keep moving northward, [that] would change the iconic vision of Maine. As the climate warms we see them moving northward.”

For those who love the loons, that is a disturbing prediction.

Of course, as birds that are well established in Maine move northward, birds to our south with no history in Maine will start one. One example, Hitchcox said, is the tufted titmouse, a bird species almost never seen in Maine in the 1950s but now a growing population, possibly because of a warming climate

And there will be other bird species moving to Maine Hitchcox said.

"A lot of species, typically more southern ranging, now are expanding northward," he said. "That’s definitely a result of it getting warmer.”

Hitchcox, who is in his early 30s, added that such major changes could happen within his lifetime if the warming of the climate cannot be slowed.

Tune in at 6 p.m. Thursday to learn more about how a changing climate is threatening Maine's birds.