BELFAST, Northern Ireland — The first time George Mitchell came to Belfast, it was a war-scarred city of bomb damage and barbed wire.

This week the former U.S. senator returned, perhaps for the last time, to a city at peace — a peace he was crucial to forging.

Now 89 and being treated for leukemia, Mitchell has not attended a major public event for three years. But he was determined to be in Belfast to mark the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, the 1998 peace accord he helped to bring about.

“I love Northern Ireland. I love the people. I love the place. They’ve been extraordinarily generous and hospitable to me and my wife, my family,” Mitchell told The Associated Press on Tuesday at Queen’s University Belfast. “The fact that it might be my last time makes it especially meaningful for me.”

With a political crisis that has toppled Northern Ireland's power-sharing government clouding the peace commemorations, Mitchell said the Good Friday Agreement has been “a remarkable success, but much more is needed” to deliver on its promise.

“No one ever said, ‘This solves all of our problems for all time,’” he said. “Because life is change and the seeds of a new problem are created every time you deal with an old problem.”

A lawyer and judge before entering politics, Mitchell spent 14 years as a U.S. senator for Maine — six of them as Democratic majority leader — before President Bill Clinton asked him in 1995 to become a special envoy to Northern Ireland.

Clinton said he described it to Mitchell as an “easy little part-time job” that wouldn’t take much time.

“For 25-plus years now he’s been reminding me of how misleading I was about that little part-time job I asked him to take,” Clinton said Monday.

When Mitchell took the post, Northern Ireland was embroiled in “The Troubles,” a conflict involving Irish republican militants, British loyalist paramilitaries and U.K. troops that erupted at the end of the 1960s. More than 3,600 people, mostly civilians, were killed in bombings and shootings.

Mitchell ended up chairing three separate sets of peace talks over five years, doggedly coaching and cajoling Northern Ireland’s antagonistic parties towards peace — despite walkouts, shouting matches and deadly attacks that threatened to derail the process.

“It seemed like 50 years at the time,” he said. “But we persevered and prevailed.”

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair said that “in the frenzy of Northern Ireland politics, George was this soothing balm. … He created just the right atmosphere for people to talk to each other.”

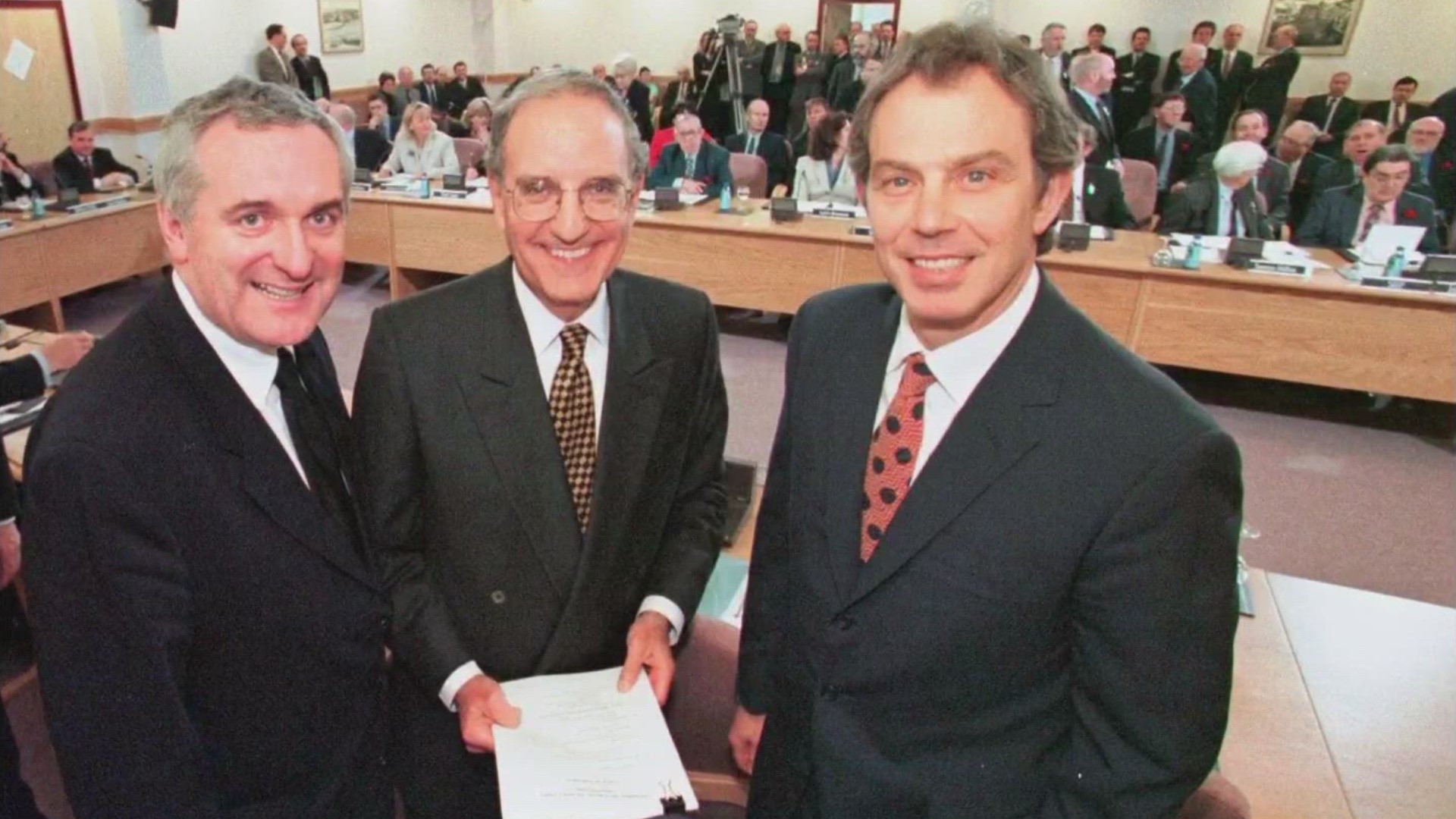

On April 10, 1998 — Good Friday – an agreement was reached that got paramilitaries to lay down their arms, ended direct British rule and established a power-sharing unionist-nationalist government for Northern Ireland.

Twenty-five years on, Northern Ireland is a transformed place, where shiny glass buildings in Belfast are testament to peace and economic energy. But deep divisions remain, and the working-class neighborhoods that bore the brunt of the violence still suffer from poverty and a lack of opportunities.

“There remain large parts of the population that haven’t seen growth, haven’t seen opportunity, haven’t seen better jobs, better lives and, most importantly, better opportunities for their children,” Mitchell said.

Power-sharing has faced several crises, most recently a walkout by the main unionist party that has left Northern Ireland without a government for more than a year. Mitchell said it’s essential to get the Belfast government back up and running.

“The people of Northern Ireland are entitled to and deserve self-government,” he said. "And it can be fixed only by the political leaders who are involved in dealing with the issues.

“They’ve got to show the same courage and vision that their predecessors showed 25 years ago in far more difficult and dangerous circumstances then. And it seems to me that you can’t take the first ‘No’ as the last ‘No.’ You have to stay with it and figure out a way to bring people to a compromise.”

Years after the Northern Ireland agreement, President Barack Obama hoped Mitchell could bring his compromise-fostering skills to the Israeli-Palestinian divide and appointed him a special envoy for Middle East peace in 2009. He resigned in frustration two years later.

In Belfast, he is a celebrity. He got a standing ovation from theatregoers when he attended “Agreement,” a play about the peace talks, in which he features as a character.

On Monday, a large bronze bust of Mitchell was unveiled in a quadrangle at Queen’s University, where he served as chancellor between 1999 and 2009.

“When you’re looking at a statue of yourself, you know the end is near,” he quipped.

Mitchell says he fell in love with Northern Ireland and its people, in part because its countryside, tough winters and hardy residents reminded him of his native Maine.

It also provided a link to his father, the Boston-born son of Irish immigrants who grew up in an adoptive family and never knew about his roots.

“My father did not know of, didn’t experience, had no sense of his Irish heritage,” Mitchell said. “I never heard him say the word Ireland. But when I came here. I got a sense of what my father’s heritage was.

"And I like to think he’s up there looking down at me, pleased that I’ve been able to gain a sense of his heritage that he never understood or knew.“