WASHINGTON — A Florida woman who entered the U.S. Capitol as part of a stack of Oath Keepers on Jan. 6 blamed her husband Wednesday, telling a federal judge she never would have gone inside if she weren’t following him.

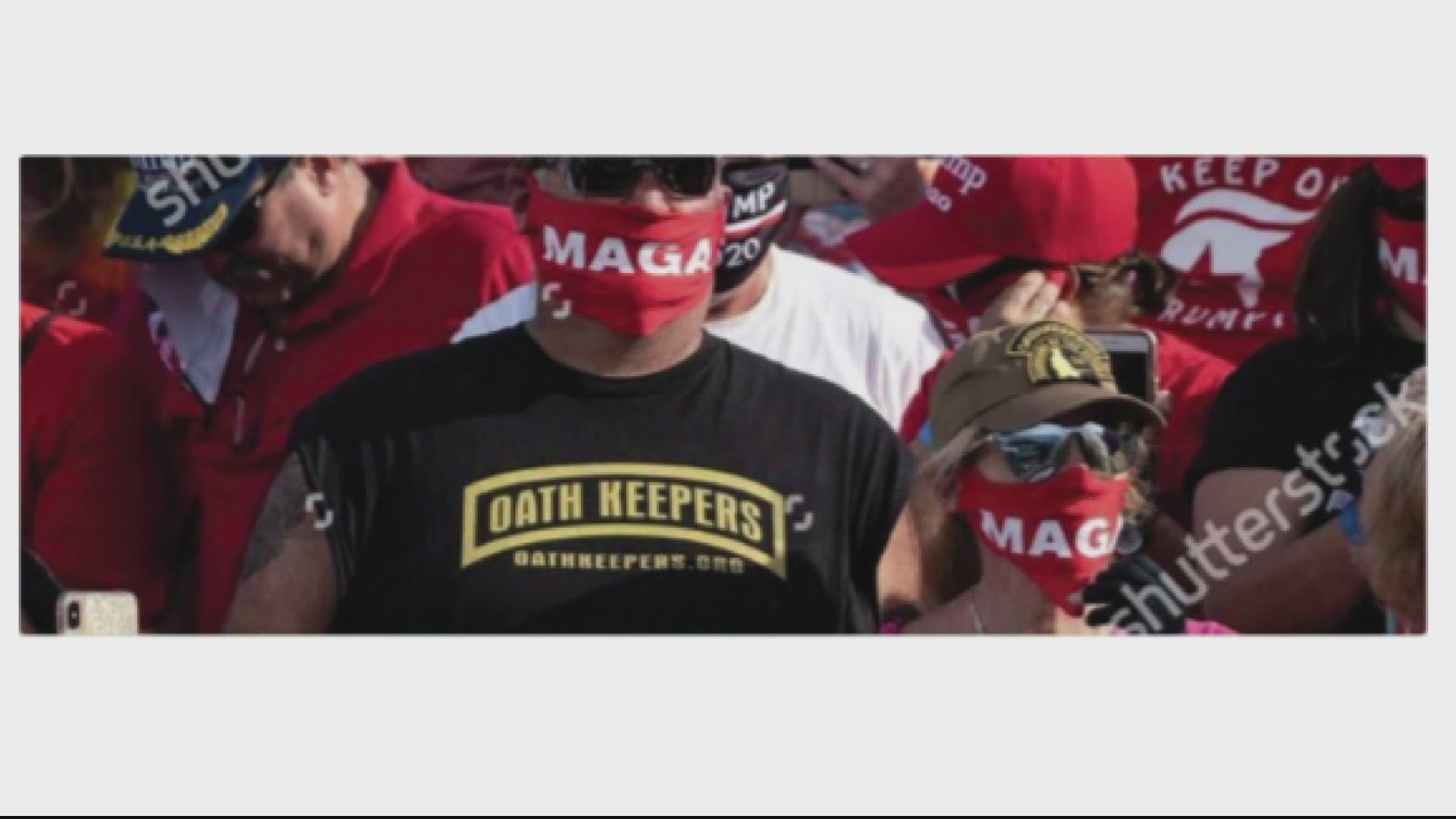

Connie Meggs, 62, of Dunnellon, Florida, was convicted in March of multiple felony counts for conspiring to obstruct the joint session of Congress on Jan. 6. On Wednesday, she was sentenced to 15 months in prison for her role in the riot. She’s one of more than 20 people associated with the Oath Keepers, including its founder Stewart Rhodes, now convicted in connection with the attack on the Capitol.

Meggs appeared before U.S. District Judge Amit P. Mehta on Wednesday for sentencing. Although she blamed Rhodes for corrupting the Oath Keepers organization – which had for years billed itself as a community response group made up of military veterans and first responders – Meggs directed most of her ire at her husband, Kelly Meggs, who served as the militia’s Florida state leader. Meggs was convicted alongside Rhodes in November of seditious conspiracy and sentenced in May to 12 years in prison.

“I was trusting my husband to keep us safe,” Meggs said. “He’s put our whole family through hell.”

Meggs presented a difficult sentencing challenge for Mehta, who has presided over all of the Oath Keepers cases charged to date in connection with the riot. While evidence showed she’d entered the Capitol in paramilitary gear alongside her husband and other Oath Keepers – and had taken part in what the DOJ described as “gunfight-oriented training” in Florida prior to coming to D.C. – Mehta said there was no evidence she was on any of the group’s numerous planning chats or was even a member of the militia. He also said he didn't doubt the "poisonous" influence Kelly Meggs had on her and others.

At trial, another Oath Keeper, Caleb Berry, testified that Kelly Meggs had called the militia members into a huddle and told them they were going into the Capitol to “try to stop the vote count.” On Wednesday, Meggs said she never heard her husband say that. Her attorney, Stanley Woodward, argued there was no evidence showing her intent at all other than a single message sent on the evening of Jan. 6.

Woodward sought a sentence that would have kept Meggs out of jail – either probation or a time-served sentence for the 45 days she spent behind bars in Florida following her arrest in February 2021. Federal prosecutors sought a much higher sentence, although Assistant U.S. Attorney Troy Edwards acknowledged Mehta’s decision would likely be constrained by sentences he’d imposed on other members of the militia who were, unlike Meggs, convicted of the more serious offense of seditious conspiracy. At the lowest end of those sentences was Edward Vallejo, an Arizona Army veteran sentenced in June to three years in prison.

Meggs faced a recommended sentencing guideline of 97-121 months, or roughly eight-to-10 years, in prison. Mehta made it clear he felt that guideline was “overly harsh” and he would be varying downward significantly as he has in other Jan. 6 cases. But he also said he felt Meggs, though obviously remorseful about the devastating effect the arrest of her and her husband have had on their family, hadn’t entirely taken to heart what she’d done on Jan. 6.

“The decisions that were made that day were also your decisions,” Mehta said. “You decided to come to Washington with a truck full of guns. You decided to go up those steps. You decided to follow Kelly Meggs into Speaker Pelosi’s suite.”

Ultimately, Mehta sentenced Meggs to 15 months in prison and three years of supervised release. She will also have to pay $500 in restitution. Mehta granted a request from Woodward to recommend she be placed at the minimum security facility at FCI Coleman in Florida. According to Bureau of Prisons records, as of Wednesday her husband Kelly Meggs was at the federal detention center in Philadelphia.

Mehta allowed Meggs, who traveled to the hearing Wednesday with her son and two grandchildren, to return home on her current conditions of release and self-report to the Bureau of Prisons at a later date.