HOUSTON — Months before the Trump administration separated thousands of families at the U.S.-Mexico border, a “pilot program” in Texas left child-welfare officials scrambling to find empty beds for babies taken from their parents in a preview of bigger problems to come, according to a report released Thursday by congressional Democrats.

Documents in the report suggest Health and Human Services officials weren't told by the Department of Homeland Security why shelters were receiving more children taken from their parents in late 2017. It has since been revealed that DHS was operating a pilot program in El Paso, Texas, that prosecuted parents for crossing the border illegally and took their children away to HHS shelters.

“We had a shortage last night of beds for babies,” Jonathan White, a top HHS official, wrote in a Nov. 11, 2017, email. He added: “Overall, infant placements seem to be climbing over recent weeks, and we think that’s due to more separations from mothers by CBP.”

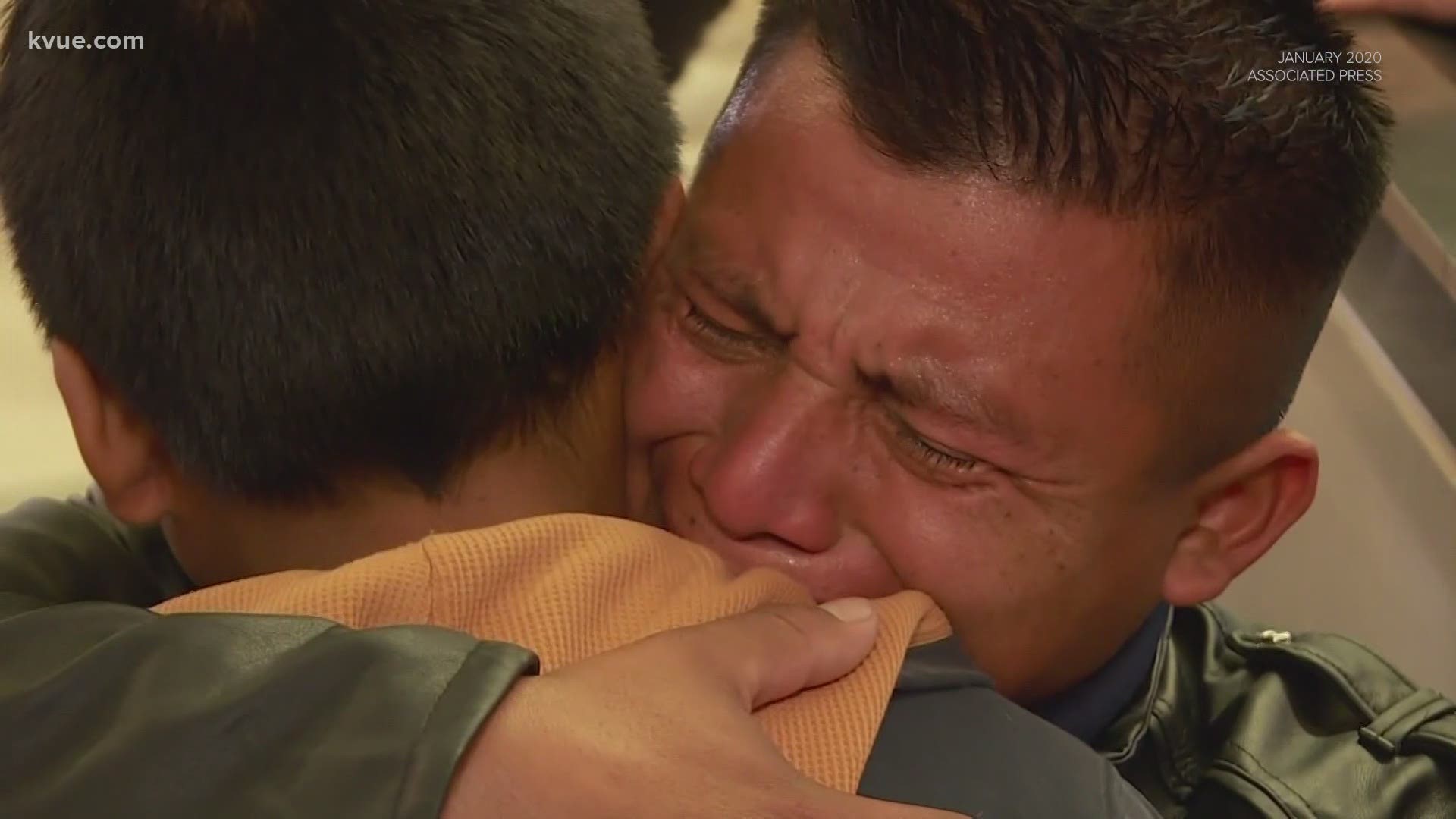

The problems revealed by the pilot program presaged what would happen months later: government employees caring for babies and young children in so-called tender age shelters and many parents being deported without their kids. The consequences linger today: Lawyers working to reunite immigrant families have said they can’t reach the deported parents of 545 children who were separated as early as July 2017.

Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee released the report Thursday with emails obtained from government agencies. It comes shortly before Election Day as Democrats campaign against the Trump administration's family separations, which stirred widespread outcry as part of its “zero tolerance" crackdown on illegal border crossings.

Democrat Joe Biden announced Thursday that he would form a task force if elected to reunite still-separated families.

The report outlines discussions since the start of the Trump administration of family separation as a law enforcement tactic. In March 2017, then-Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly told CNN that the government was considering taking children from their families and placing them in government-licensed shelters while the parents were prosecuted.

That July, Customs and Border Protection agents began separating families in what was later called a pilot program, according to a review by the Health and Human Services inspector general.

The pilot ran through November 2017. According to the inspector general, at least 118 children were taken from their parents. Documents in the new report suggest CBP did not communicate with HHS about why shelters were receiving more separated children.

White, the HHS official, wrote a Nov. 17, 2017, email to Kevin McAleenan, who was then commissioner of CBP and later became acting Homeland Security secretary. The email notes “the increase in referrals” of children unaccompanied by a parent “resulting from separation of children from parents.” White sent McAleenan a chart of all the children HHS had received.

In a Dec. 3, 2017, response, McAleenan wrote in part: “You should have seen a change the past 10 days or so. We will be coordinating in advance on any future plans.”

Another HHS official, Tricia Swartz, had written to White on Sept. 28, 2017, warning that “these types of cases often end up with parent repatriated and kid in our care for months pending home studies, international legal issues, etc.”

The pilot program is believed to have been limited to the region around El Paso, Texas, including parts of New Mexico. Months later, the Trump administration began separating families border-wide. The report documents how different Border Patrol sectors had their own policies for which families to separate: the Big Bend sector in rural Texas initially exempted children 5 and younger, while the El Centro sector in California did not.

In June 2018, U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw ordered the government to reunite all migrant families. More than two years later, the process is still underway, with lawyers and nonprofits trying to find parents in Central America and elsewhere after their children were placed with sponsors in the U.S., usually relatives.

McAleenan did not respond to a request for comment. The Homeland Security and Health and Human Services departments did not respond to requests for comment.