YARMOUTH, Maine — Federal officials have proposed a path to remove two historic dams on the Royal River in Yarmouth, the result of more than a decade of studies and discussions.

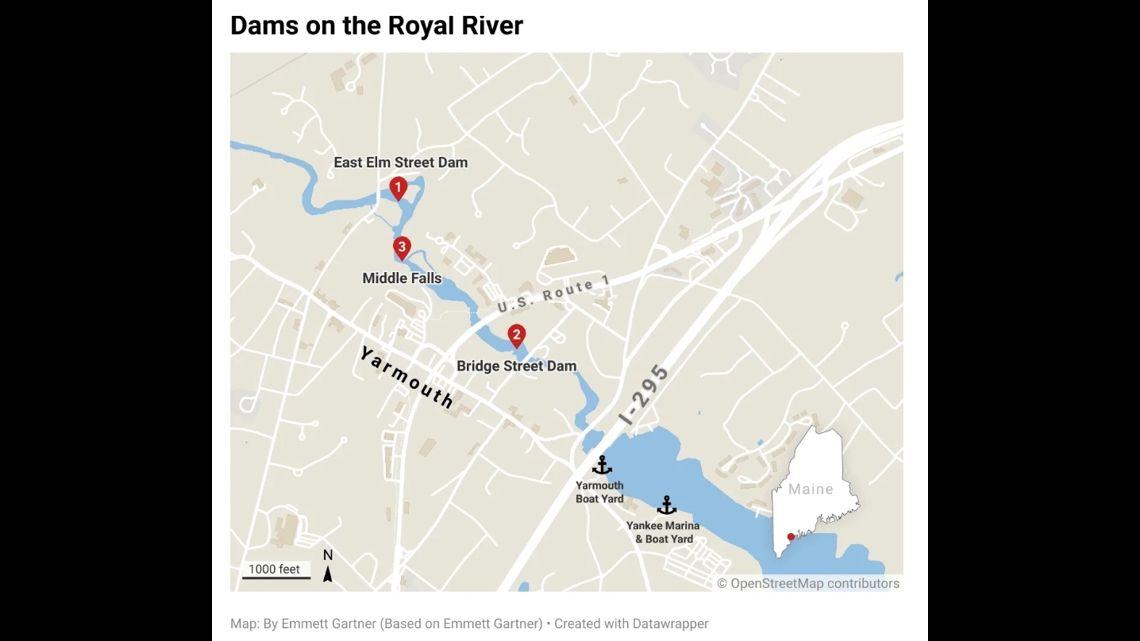

A federal proposal released in late April offers a process toward rewilding a span of the river, fully removing the Bridge Street Dam and nearly half of the East Elm Street Dam. Officials presented the plans to the town council last week.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers determined that removing the dams has the greatest potential to improve river habitat and restore fish access toward the headwaters of the Royal River, historic spawning grounds for sea-going fish like alewives that have largely disappeared upstream of the dams.

The plan is tentative and will take almost a year to finalize through environmental assessment, public comment and internal review.

But town officials said they can use it as a springboard to open their own public comment period and chart the dams’ fates.

The proposal allows the town to seek funding for its estimated $2.3 million share of the project, which could soon be sought through grants and other opportunities with the plan’s adoption, officials said.

“It’s been a long way,” said David Craig, the council chair who supports the dam removals and has waited through almost 13 years of stops and starts to reach this point. “Now that we’ve got (the plan), I’m pleased with the data supporting that we can do dam removal safely.”

Plan brings mixed emotions

Some residents and conservation groups welcome the plan.

“I think it’s going to give Yarmouth an opportunity to reconnect with its river … and see a path forward for improving its health,” said Landis Hudson, a Yarmouth resident and executive director of the nonprofit Maine Rivers. “I’m thrilled. I’m really very happy.”

Hudson said she has no problem waiting even longer as the Army Corps finalizes its proposal, time she’ll use to try and explain what dam removal looked like for other communities her organization has been involved in and help answer questions.

“It will take more conversations with people in town, fundraising, permitting and answering more questions,” Hudson said.

Alan Stearns, executive director of the Royal River Conservation Trust, an environmental nonprofit concerned with both the river and its roughly 141-square-mile watershed, is also excited about the removal.

He sees the potential for the plan to also improve Casco Bay by housing migratory fish species like brook trout, and expanding food sources for eagles, ospreys and otters.

“I think we all know that the fishery on the Royal River will never be as dramatic as the fishery of the Kennebec or Penobscot rivers,” Stearns said, “yet it’s still pivotally important to have a good fishery in a river that feeds Casco Bay.”

Others are looking for a more concrete outline from the Army Corps before giving their support.

Steve Arnold, owner of Yarmouth Boat Yard on the harbor’s southwestern shore, closest to where the river widens, has questions about the proposal’s influence on the harbor’s water.

Without the dams, Arnold is concerned the hydrological conditions his business has relied on will shift, delivering more water at a faster rate during rain events, and forcing him to remove boats and floating docks more often and quicker than usual.

“Two to three inches (of rain), we start pulling boats. Three to four, we’re going to pull docks. Four to five and we’re pulling the whole marina,” Arnold said. “That’s known. What does that look like when the dams come down?”

Another problem for Arnold is the interpretation of the Army Corps’ most recent tests on sediment contamination, and why the levels that raised alarms in a 2016 study are no longer of concern.

Bryan Purtell, an Army Corps spokesperson, said the agency “does not believe that there will be significant changes to the river below the study area,” including from sediment and the water’s projected flow.

Dredging the harbor for the marinas means undergoing similar tests on the sediment to be removed, Arnold said, and if it tests too high for certain contaminants, the sediment has to be trucked inland rather than boated away — a more expensive proposition.

Still, Arnold expressed trust in the Army Corps and the attention its members have paid him and other marina owners. He said he’s looking forward to their clarification and a better understanding of where funding will come from for the town’s estimated $2.3 million obligation.

After the town council voted to increase taxes by almost 9% earlier this month, Arnold predicted few residents would support removal if it came with another increase.

“If you demonstrate to me that my fears will not come true, then I’m on board,” said Arnold.

An industrial past

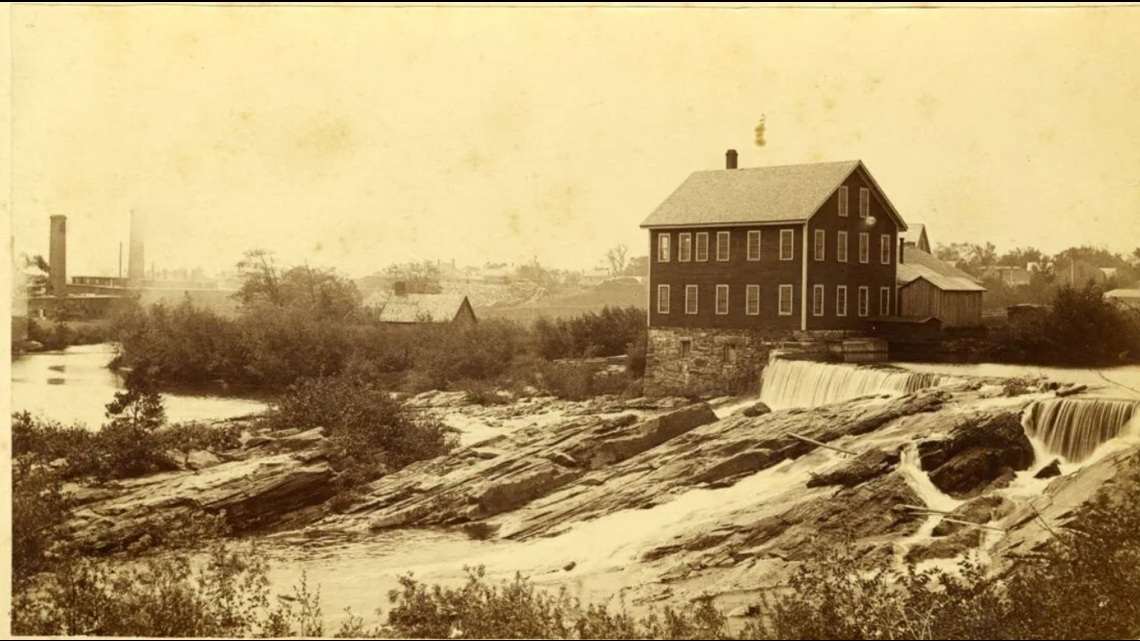

The dams sit on two of the four natural waterfalls just upstream of where the Royal River widens into the tidal flats of Yarmouth Harbor before releasing into Casco Bay.

Before the river was dammed by the English in the late 17th century and renamed for a settler, its watershed was called Wescustogo by the Wabanaki and home to the Abenaki Nation, a member of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Years of Anglo-Wabanaki war and the European introduction of novel diseases decimated Indigenous populations and weakened Wabanaki resistance to European settlements, and by 1715 the English permanently entrenched their dams and mills into the banks of the Royal River.

Decade to decade, new owners of paper, grist and cotton mills would take over a coveted spot on this section of the river and harness the cascades’ power, forming Yarmouth’s industrial core.

Built in 1870, Bridge Street Dam spans 275 feet across the tumbling whitewater of Second Falls, spending much of its useful life powering a textile mill owned by the Royal River Manufacturing Company.

The mill continued to produce cotton goods until 1951. Unlike other historic mills on the Royal, the brick structure now known as Sparhawk mill is still perched on the river’s northeast bank, and houses a restaurant and other businesses.

In 1973, the town of Yarmouth assumed ownership of the dam. The next year, the town and the Maine Department of Marine Resources attached a fishpass to its right spillway.

East Elm Street Dam underwent a similar transformation in 1979 after it was acquired by the town. At 250 feet long and 12 feet tall, it is narrower than the Bridge Street Dam and further upstream, occupying the fourth and final of the commodified falls (called ‘Upper Falls’) near the Yarmouth Historical Society.

East Elm Street Dam was built in 1890, and powered a shoe factory and other industries until the 1960s, when its accompanying buildings were demolished.

The Bridge Street Dam and Sparhawk mill were renovated for hydroelectric production around 1985, producing electricity rather than mechanical power for the first time.

Its energy-producing days were short-lived. After changing hands a few times, one of the mill’s former owners said they stopped operating the project after acquiring it in 2014. The owner then removed the turbines and generators in the mill’s basement, disconnected the project from the power grid and surrendered the dam’s federal license in 2021.

Years of studies

Momentum toward removal began when the Royal River was flagged as a restoration priority in 2005 by the Gulf of Maine Council on the Environment and a since-dissolved planning department in the governor’s office.

In 2009, the town contracted the engineering firm Stantec to survey the river corridor’s natural resources, and recommend cost-effective measures for restoring sea-run fish populations and other native species.

Stantec reported that by 2010 the dams’ fish passages had fallen into disrepair and not been serviced since sustaining flood damage the previous year. Responsibility for their maintenance became unclear after the Maine Department of Marine Resources, which previously maintained them, lost the federal funding to do so, and Stantec predicted the duties could shift to the town.

That year, like 14 years later, the recommendation to best restore fish passage upriver and reduce future maintenance costs was to remove both dams.

Yet what remained uncertain was how the river’s hydrology could change, where sediment released from behind the dams may settle downstream near the harbor, and what chemicals, if any, that sediment contains.

Those points were raised in public meetings after the initial report, according to Stantec, and have been emphasized by marina owners over the years. Their businesses line the banks of the tidal flats at Yarmouth Harbor where the river opens up, a little more than a quarter-mile from the Bridge Street Dam.

So Stantec returned three years later with a fresh study predicting that removal could send more sediment to the harbor during small floods, but probably not larger ones, and the immediate impact of removal would only depend on whether those small-scale floods were to follow.

Sediment already meanders to the harbor with the dams in place, the study noted, and dredging needs to occur regardless.

Samples of sediments taken from behind the dams and downstream showed a small difference between each location’s levels of chemical contamination. Meaning if the built-up sediment behind the dams was released with removal, there would be “minimal potential risk of adverse effects to aquatic life” from its level of contamination.

If the East Elm Street Dam is removed, the impoundment the dam currently creates could become too shallow for boats entering from the Yarmouth History Center’s launch, according to the report.

But the firm predicted that the 5 to 6 feet lowering of the river’s upstream water levels would not adversely affect activities beyond the East Elm Street Dam’s impoundment up to the Route 9 bridge, toward North Yarmouth.

Ultimately the projected cost of the proposed removal — up to $3 million — bogged down progress, so Yarmouth officials requested assistance from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to share the costs and put a more formal plan together.

Then the town waited. And waited.

“They said they’d dance with us, but now they won’t get out of their seat,” then-town manager Nat Tupper told the Portland Press Herald in 2013.

A year later the Army Corps announced it would spend $3 million to dredge Yarmouth Harbor after a more than decade-long delay. Dam removal then fell to the wayside and was ultimately tabled by the town council in 2015.

But working in the background of these intervening years, were environmental advocacy groups like Maine Rivers and Royal River Conservation Trust, vying for dam removal and nudging town councilors toward the ecological benefits that research showed could come with it.

Then a new study was done that made some question whether removal was the right path. A 2016 test conducted by Stantec and paid for by The Nature Conservancy indicated that sediment behind the Bridge Street Dam had slightly elevated amounts of chemicals like mercury after all.

Later analysis from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and published by The Nature Conservancy indicated that the sampled contaminants came from stormwater runoff rather than the suspected legacy industries, and their concentrations were well below what would likely affect animals.

After a brief flurry of headlines, the debate again went dormant, but the results still remain a sticking point for some.

Then, in 2020, after seven years of little activity, the Army Corps committed to investigating restoration of the Royal River.

Town councilors voted in early 2021 to match the $55,000 funding requirement for the first phase of the project. Another round of studies commenced, but the stop-and-go progress that has plagued discussion of the Royal River followed.

The Army Corps team encountered delays and underwent leadership changes that slowed the plans, finally releasing a significant report in January affirming that sediments sampled behind the dams “pose minimal potential risk to the marine environment in the Royal River estuary and Casco Bay under any of the proposed restoration project alternatives.”

In April, the Corps brought forward a tentative plan to remove the structures.

Along with dismantling much of the dams, the plan calls for placing boulders and creating a channel for fish passage at Middle Falls — the third set of cascades where remnants of the Forest Paper Company’s mill complex, the old town’s largest industry, are still evident.

It would leave a sliver of the East Elm Street dam on the river’s northern bank, below a house. The plan would not affect any private property and physical impacts would be restricted to a drawdown behind the dams, and changes in river shape and vegetation associated with the drawdown, according to the Army Corps.

“There’s just so many more benefits if you remove all of the impediments to fish passage. It’s just the way fish passage works,” said Janet Cote, the Army Corps project manager, at a meeting this month unveiling the plan. “If we can return those alewife and migratory fish runs, we’ll increase productivity of the Royal River.”

The Army Corps is slated to release a more finalized draft of its study and environmental assessment at an in-person public meeting in June.

The town could then vote on whether to endorse and adopt the recommendation or something different, according to Town Manager Scott LaFlamme, which the Army Corps will use to develop engineering designs.

Craig said he is committed to holding an open and public process as the town wades through these decisions, even if it takes years. His priorities are to find funding and host an inclusive discussion.

“The intent is not to stick the taxpayers with a $2 million deal,” Craig said. “The nice thing about finally having a plan is now we can go out and try to find those grants. This is the key to starting that process.”

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.