WISCASSET, Maine — Howard Cederlund said the U.S. was fighting three enemies across two oceans when he left high school to join the Navy in 1944. He was just 17 years old.

“It seemed everybody was going in,” he recalled, 78 years later.

“They were trying to save the country, and I was no different.”

When asked about the obvious danger all those in uniform could face, Cederlund had a simple answer.

“Yeah, I don’t think I expected to come back. I don’t think any of us did.”

He enlisted in July, before the start of his junior year of high school in Massachusetts. Nine months later, he was in combat in the Pacific, as a cunner on the USS Menard, a ship carrying soldiers and Marines to invade Okinawa.

“I was 17 when I left, seventeen when we got to Okinawa. And on April 1 we invaded Okinawa. On March 30 I turned 18.”

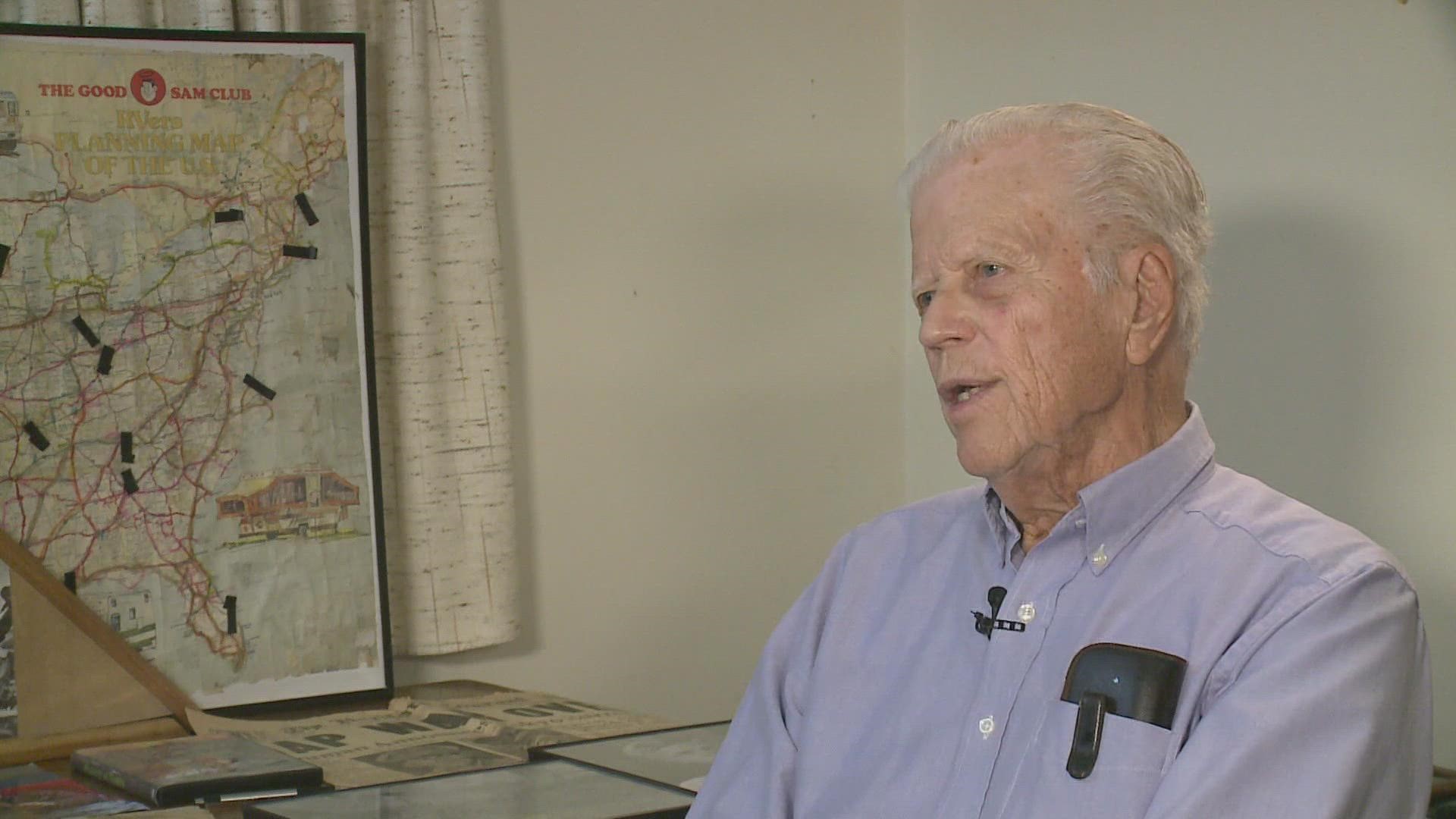

Today, at age 95, Howard said the memory of that fight is still sharp, the details of a close call with Japanese kamikaze planes engraved in his mind.

The Japanese had started using kamikaze attacks before that battle, but he said the number of those attacked on the Navy’s Okinawa fleet was intense.

“On the 6th of April, 310 kamikazes came after us, with 300 escorts in a four-hour period, and one of them had our name on it for sure.”

Howard recalled how he was at his gun as the plane took aim at his chip.

78 years have not dulled that memory.

“He came over the island of Okinawa, coming right at us, but the hospital ship Comfort was between us and the island. At first I thought he would hit the Comfort, but then he came for us.

Howard said he and other gunners were firing at the plane, but didn't know if any of them hit it, or if the volume of fire made it miss.

Just barely.

“And flew ten feet over my head. I’ve often said, 'Look, that’s how close I came to being hit.' Ten feet over my head and then splashed into the water, off the port bow. But I was lucky. I picked shrapnel out of my pants and shoes, while a lot of friends got wounded.

The brutal Battle of Okinawa lasted nearly three months, but Howard said the USS Menard left long before the battle ended. The ship went to another island, where it prepared for the expected invasion of Japan itself — an attack expected to cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

But that assault never came, because the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which forced Japan to surrender.

“Joy,” Howard said, describing his reaction when he heard of the bombs being dropped.

“Because the war is going to end. The U.S. has a secret bomb that will end the war. Great joy, because you [know] what happened on Okinawa.”

About a month later, he said, the USS Menard led several other ships into Nagasaki harbor. It was a sobering reminder, he said, of what could have been their fate.

“As it turned out, we were the first ship into Nagasaki, the lead ship, and that’s what we were going to do if the battle had taken place for Nagasaki. [We] would have been the lead ship into there, and I don’t think we would have survived."

For the remainder of his time in the Navy, Howard said, the ship ferried U.S. soldiers into Japan, and took others home to the U.S. He said soldiers referred to the ship on those trips as the “magic carpet."

Howard was discharged from the Navy when he was just 19. He tried going back to finish high school, but felt out of place.

“Absolutely. I was a man, I went to Commerce High to see about finishing my education, and saw all these kids and said they seemed so young, I can’t do this.”

Instead, he went to work in a manufacturing plant in Worcester, was promoted into management and stayed 25 years, eventually helping the company learn to use computers. Howard said he also had several businesses of his own on the side during that time. He eventually bought a sawmill in Wiscasset and moved to Maine, where he lives today.

He has compiled a detailed notebook of his time in the Navy, the Battle of Okinawa, reunions of the USS Menard crew and more. He said he may be the last living member of that crew, and wants to make sure their story is told.

Asked if he is proud of serving in the war, Howard didn’t hesitate.

“Very proud — that I could go and help stop a war."

But then thoughts of modern conflicts, such as Ukraine, come to mind, and Howard said he sometimes gets angry.

“And you see what’s happening now, old men starting wars, and its crazy.”