BUXTON, Maine — Colleges in New England are facing a dire forecast: in the next ten years, 15 percent fewer students will go to a four-year college.

The data comes from EAB, a consulting and research firm that colleges enlist to help them recruit students. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics finds similar drop-offs.

This forecast comes as at least six private liberal arts colleges in New England have announced they will close their doors by May of 2019.

Since 2016, four Vermont colleges (Southern Vermont College, Green Mountain College, Burlington College, and College of St. Joseph), as well as two Massachusetts colleges (Newbury College and Atlantic Union College) announced plans to close.

Southern Vermont, Green Mountain, College of St. Joseph, and Newbury all close at the end of the Spring 2019 semester, coming up in just a few days.

Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass. announced it would not admit any new students for the fall of 2019 or spring of 2020.

Three other colleges announced they would merge with larger universities: Mount Ida College in Newton, Mass. is becoming part of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Wheelock College in Boston is merging with Boston University.

In 2016, Johnson State College and Lyndon State College in Vermont “unified” to become Northern Vermont University. While NVU is one university, the campuses still have their distinct identities, with separate mascots, athletic teams, and alumni associations.

Many of the schools offer “teach-out” options: A teach-out agreement is a written agreement between institutions that provides for the equitable treatment of students when one of those institutions has stopped offering an educational program before all students enrolled in that program completed the program.

For example, students from Green Mountain College can enroll in a variety of schools, including two Maine schools: Unity College and College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor.

Windham, Maine native Tara Carroll is about to complete her sophomore year at Green Mountain this May. She is trying to decide whether to take a semester off or attend one of the teach-out options.

“We honestly had no idea,” Carroll said of the day students and faculty were told the college would close. “The president of our college didn’t know until that morning if we were going to be able to stay open or not. Everyone in that room was heartbroken.”

Carroll said the small class sizes, some as small as eight students, and the close relationships with professors make being forced to leave Green Mountain that much harder.

“If I had known my senior high school that this school was closing, I probably wouldn’t have gone, but I’m so glad that I didn’t know at that time because the amount I’ve learned and community I’ve built for myself and the support system I’ve built for myself is comparative to nothing , and I would not ever take that back,” Carroll said.

She said College of the Atlantic would not accept her adventure education credits that she is taking for her minor.

“I would quite literally be losing money,” Carroll said.

She said some students who were getting financial aid for being in-state students were not able to get that same aid at some of the teach-out options.

Other students are having an easier time finding a good fit. The mother of Cameron Deiley, a 2017 graduate of South Portland High School who attended Newbury College, wrote, "his initial reaction was 'This sucks!' but the school did a phenomenal job communicating and getting transfer agreements in place for their students." Her son is set to attend Lasell College in Newton, Mass. next semester, where they matched his financial package.

WHY ARE PRIVATE LIBERAL ARTS SCHOOLS CLOSING AT THIS RATE?

According to Kim Morrison, the senior college consultant at the South Portland-based “College Solutions,” there are two main factors: endowments, and the shrinking college-going population.

As a consultant, Morrison helps students decide which institutions would be the best fit for them, and looks at research and data from all over the country to help guide their decisions. She said in the cases of the schools that recently closed, graduates typically end up with jobs outside of corporate America.

While that does not mean graduates are not earning enough money, she believes they are not earning enough to help replenish the endowments schools rely on as part of their budgets.

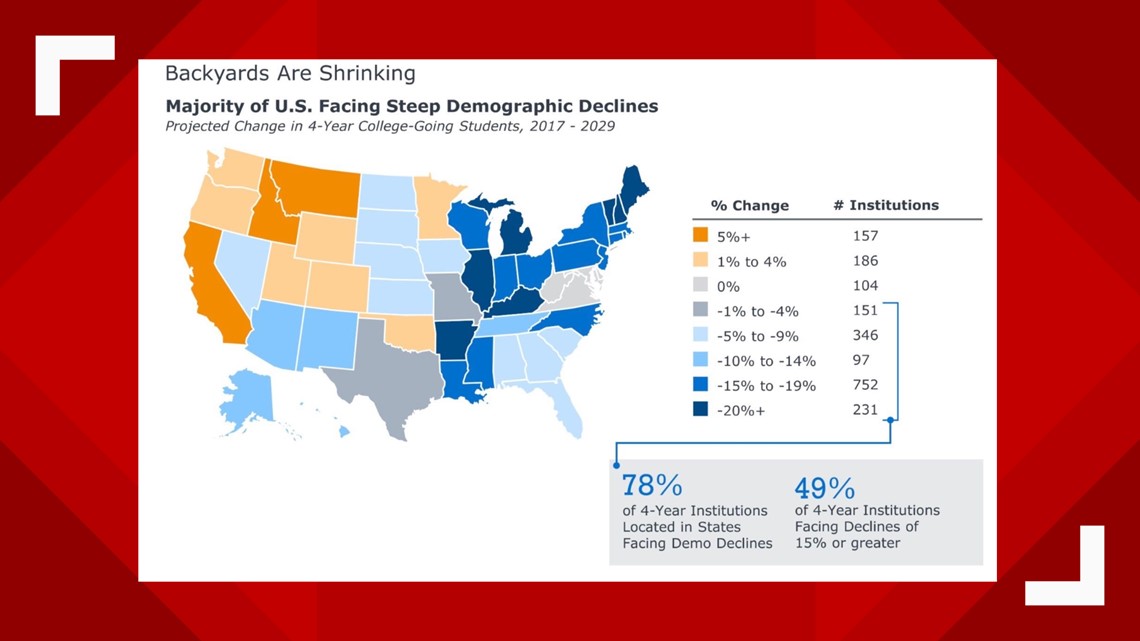

A big factor in receiving donations to build and sustain endowments is the college-going population, which the EAB study shows will drop precipitously: Morrison agrees.

“The population of college-going students is literally going to drop off a cliff,” said Morrison. “The weaker institutions are already seeing a decline in endowment or enrollment.”

‘TRICKLE DOWN EFFECT’

Morrison said that because of the dip in population, schools are admitting more students and/or offering more financial aid, causing a “trickle-down effect.”

In order to maintain enrollment, a very strong school academically might “dip” into a pool of students that typically would fall outside of the school’s admittance parameters.

The terms “Reach,” “Match,” and “Safety” come to mind. A “Reach” school is one a student is less likely to get accepted to. A “Safety” is a school a student expects they would almost definitely be accepted to.

Morrison described an example where a student gets accepted to a “Reach” school, foregoing enrollment at their “Match.” Those “Match” schools would have to dip into a pool of students that might not typically get admitted. That leaves weaker schools with higher acceptance rates struggling to actually enroll students who are getting better offers to more prestigious schools.

“Nobody’s going to choose to go down when they can go up,” said Morrison. “The schools [students] should definitely get into, what we call a reasonable choice, sometimes they don’t even get into those schools because the waters are muddied by students that are incredibly strong,” said Morrison.

On the other side of that phenomenon, fewer students are attending those “weaker” schools, schools that also happen to have acceptance rates above 75 percent.

Data from the National Center for Educational Statistics show that Green Mountain College had a student population of 468 undergraduates in 2018. Southern Vermont College had 361 undergraduates in 2018. College of St. Joseph had 237.

“Colleges now have higher overhead,” said Morrison. “Colleges don’t want to have empty beds.”

That trickle-down effect is hitting these smaller private liberal arts schools, often with specialized programs or less traditional academic structure.

“I become fearful when [schools] start getting rid of [majors],” Morrison said. “That could be a first step in a school starting to restructure financially.”

But why New England?

Morrison said New England already has a smaller population overall, and with many rural areas with lower incomes, there are fewer students that are attractive to schools already admitting increasingly stronger student pools compared to the colleges’ past admittance classes.

She understands that for students like Tara Carroll, having to pick a new college in the middle of their academic career can be rattling.

“What’s more difficult to find a college that will accept them and graduate them if they’re just finishing up their junior year. Many colleges require that at least half of a student’s credits must come from that institution alone,” said Morrison.

Carroll has narrowed her options, considering teach-out options at Prescott College in Arizona, or Sterling College in Vermont. She is also considering taking a semester off.

She said some students who were close to graduation loaded up their spring semester, taking nearly 30 credits in order to be eligible to walk at graduation before Green Mountain closes for good.

For Carroll, that is not an option, but said that she is confident that her next step does not determine the value of her time at the small private liberal arts college in Poultney.

“I think education is an investment, but I wouldn’t say I’m losing money because of what I learned.”