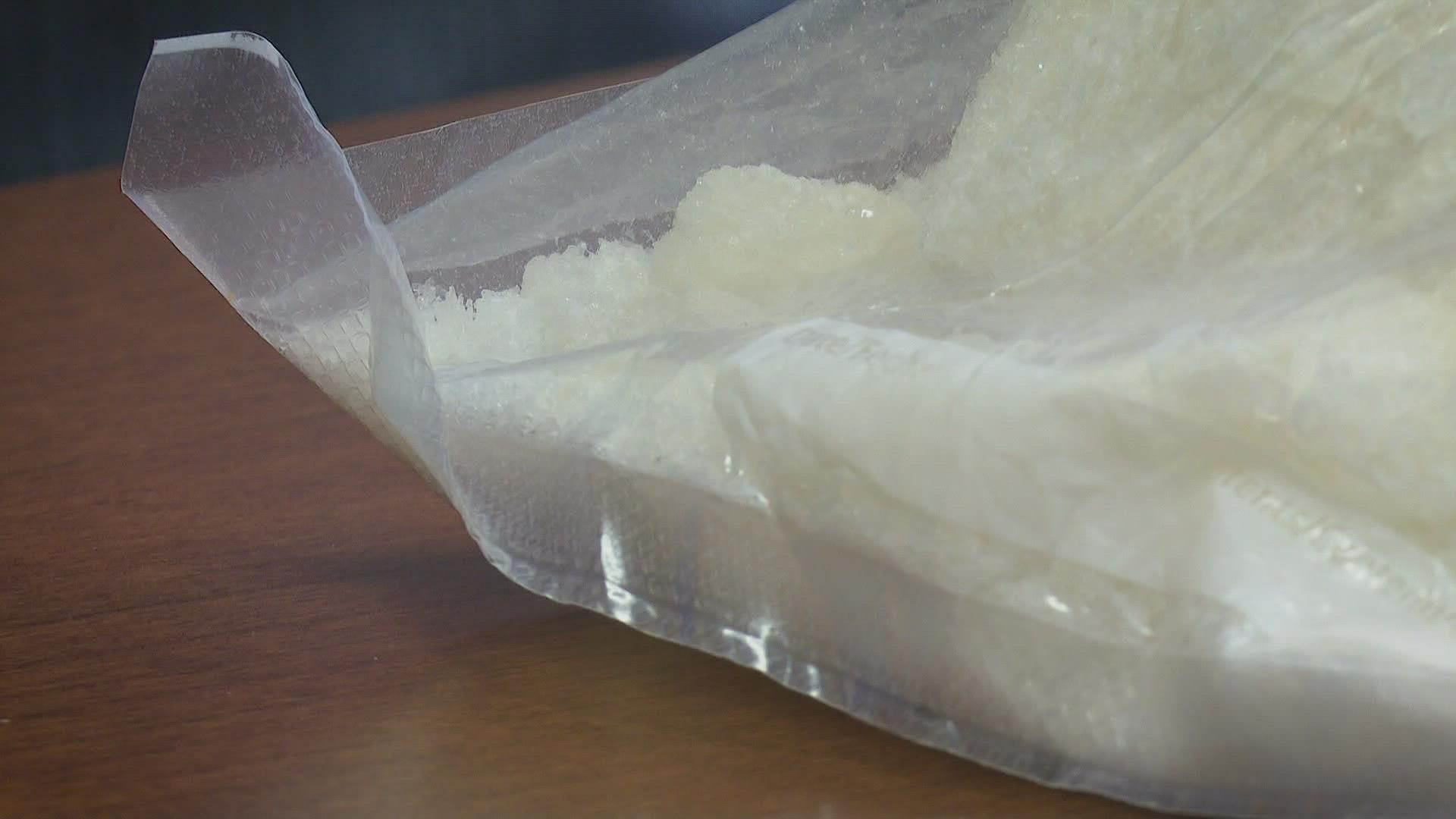

PORTLAND, Maine — Maine drug agents are seizing more methamphetamines than years past as trafficking into the state reaches new heights.

In 2021, the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency seized 8,561 grams of methamphetamine. The year before, agents seized 2,117 grams. In 2019, they seized 2,718 grams. Already this year, through March of 2022, agents said they had seized more than 1,400 grams. Cmdr. Scott Pelletier said he expects 2022 seizures to exceed 2021 numbers.

"The availability has increased two-, three-fold," Pelletier said. "The potency is very high. The addiction rate or the reuse rate is very high."

He said crystal meth is stronger and more addictive than "dirty meth," which people can make at home using materials including battery acid.

Pelletier said the same dealers who are bringing fentanyl and cocaine to Maine are trafficking in crystal meth.

"Those drugs, fentanyl, cocaine, methamphetamine. It's a one-stop-shop now," Pelletier said.

Data from the state show fentanyl was at least partly responsible for 77 percent of deadly overdoses in 2021, up from 67 percent in 2020. However, drug agents and recovery advocates say most people using drugs are using a combination, not one single drug.

"Somebody might think they're taking cocaine or meth and not even realize it has fentanyl mixed in with it and then it becomes really, really dangerous. It's like Russian Roulette. It's heartbreaking," Leslie Clark, executive director of the Portland Recovery Community Center, said.

Clark said the Center's Crystal Meth Users Anonymous group has roughly 100 members, more than any other group at the Center, and a number that is growing.

"When those programs and our services are growing, that's a good thing, because that means people are finding us and finding their way out of addiction," Clark said.

But getting people treatment for methamphetamine, a stimulant, is very different than treatment for opioids. According to Ben Strick, director of adult behavioral health for Spurwink, detoxing from opioid use can involve taking lower-strength opioids like buprenorphine to mitigate cravings and other withdrawal symptoms.

"It's a very, very hard drug to establish recovery with or from," Strick said.

But it is not impossible. Two men working at a law-firm in Portland, Matt and Shane, shared their story of using and recovering from meth. They asked for their last names to remain unidentified out of fear of judgment and stigma.

"Once I started using it, I really didn't stop," Matt said. "The high is this incredible rush, this kind of superman-type power. The comedown is a very dark depression. I would say it brought me close to suicide."

Matt started using crystal meth at age 36 but became sober nearly four years ago.

"After experiencing that crash the first few times, I was so afraid of it that I did whatever I could to prevent from crashing, which meant finding ways to use more and more," he said.

After hitting a low point, losing his job, his car, his home, and his relationships, a close friend helped him get into treatment.

"They say that addiction is the opposite of connection, and when I'm connected with other people I don't feel the need to use drugs and alcohol."

Strick and the Greater Portland Addiction Collaborative are trying to get funding for a treatment called "contingency management." The process essentially offers rewards such as prizes, vouchers, or cash for people who consistently produce a negative toxicology screening or drug test. The federal government does not fund this type of treatment at this time.

Strick is hoping to establish a pilot program in Maine.

"The federal barriers still exist, but could be overcome with outside funding," Strick wrote in an email.