LEWISTON, Maine —

'Art has the power to help process and heal'

How do you pay proper respect to a great loss while people are still raw from the pain?

The Maine Museum of Innovation, Learning, and Labor in Lewiston took on the task of honoring, teaching, and healing in the years that follow the Oct. 25, 2023, mass shooting, during which 18 people were killed and 13 more were injured.

Rachel Ferrante is the museum's executive director. I visited her on a day in September at the Canal Street space, where she and artist Tanja Hollander were putting together an installation coinciding with the one-year mark.

"This is the most important work I've ever done," Ferrante said. "I know it's helping lots of people, and that's all you can really hope for if you're running a museum."

In December, we followed Ferrante and Hollander as they and volunteers collected more than 1,000 memorial items from the two shooting scenes: Just-in-Time Recreation and Schemengees Bar & Grille. They wanted to preserve the items before they risked being ruined by winter storms.

Among the hand-written signs, crosses, and stuffed animals, visitors left many bouquets of flowers. However beautiful, they would eventually decompose and could not be saved. But the pair found meaning in something that would otherwise be thrown away.

"I saved the sleeves, and I didn't exactly know why," Hollander recalled. "I remember calling Rachel and being like, 'Are we saving sleeves?' And she was like, 'No, why would we do that?' And I was like, 'I don't know, but I feel like we need to.'"

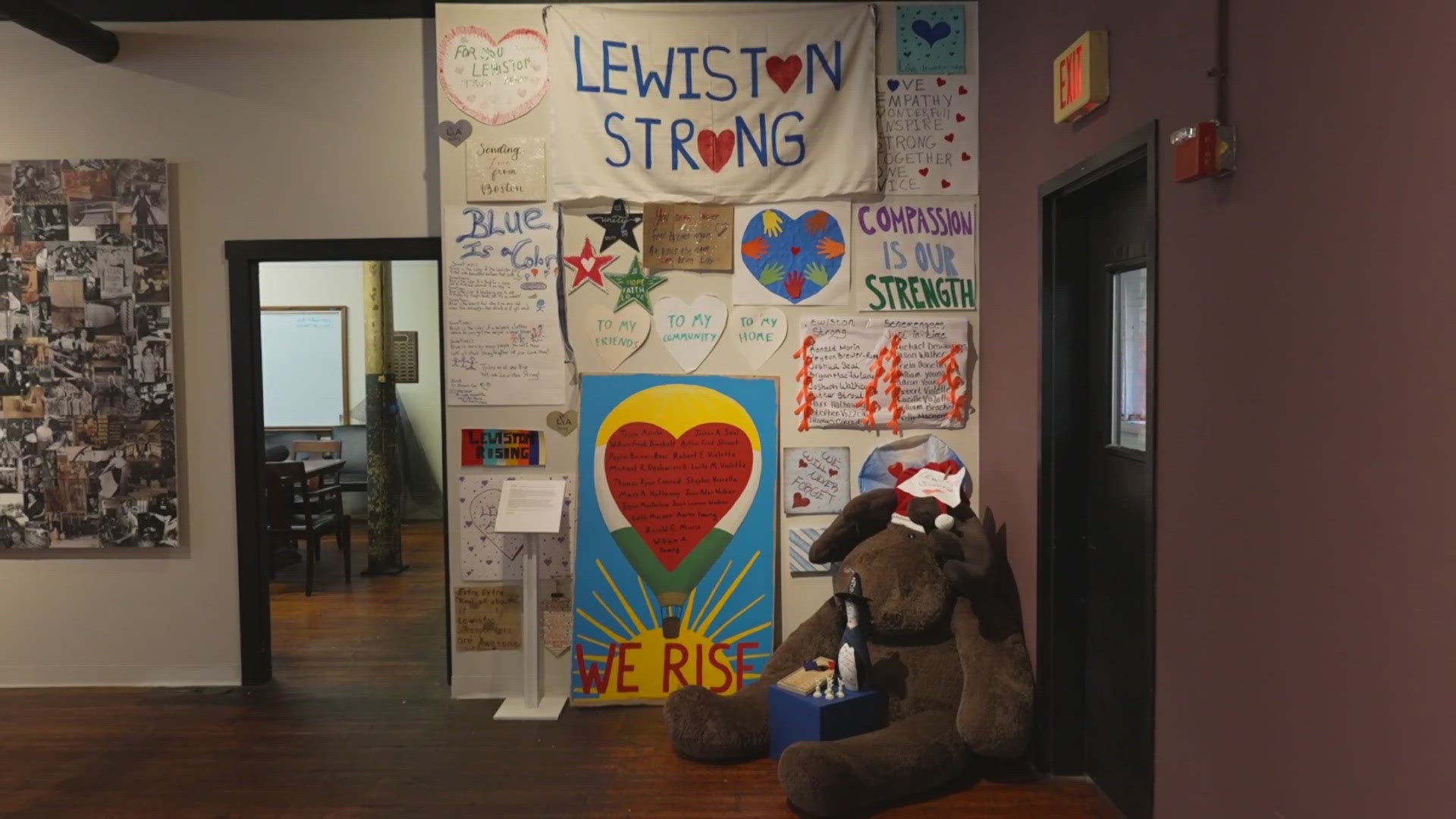

Ferrante and her team created a colorful corner of the large brick space, filled with many of the signs, notes, and other memorials saved from outdoors. There, the 261 plastic flower sleeves would become the museum's latest exhibit. I watched Ferrante and Hollander suspend the sleeves from the ceiling. Some were grouped together while others hung alone.

Look at the groups of sleeves, Hollander noted, which symbolize the collective trauma we, as Mainers, are still processing. Look closer, and you'll see that each sleeve is as it was the day it was placed on the ground.

"Some of them have petals stuck to the inside, which I find really beautiful. Some of them look pristine, and some of them are pretty beat up," Hollander said.

"Art really does have a powerful impact on people. In this particular case, I would say art has the power to help process and heal," Ferrante elaborated.

Deeper into the brick building, the museum is not only holding onto more memorials, but artifacts.

Ferrante led me to a large storage room and unlocked the door. She did so only after discussing how she wished the space to be filmed. Though I had watched on that December morning the delicate care with which she, Hollander, volunteers, and city workers removed, relocated, and catalogued the memorials, she had to keep some of the items stored out of view while the museum rotated exhibits and finalized plans for a new, permanent space. She wanted news viewers to know that these pieces were as important as any others and would also be shown to the public again in due time.

Ferrante walked toward the back of the storage room to show me some of those pieces, but I stopped dead in my tracks, midway through the room.

Leaning upright against a pillar were the two front doors from Just-in-Time Recreation. White and blue font on a black background greeted customers midway up the doors, with images of bowling balls and pins lining the bottom. The bowling alley was the shooter's first target that October night.

While law enforcement officers frantically searched for him, investigators released an image snapped by the business's security camera as he entered the building with a rifle. That image of the shooter walking through the doors, just before he was about to commit the worst acts of violence Maine had ever seen, was flashed on television screens and websites across the world as police continued their search.

When Just-in-Time's owners changed out the front doors to reopen their business to the community, they could have thrown the old ones in the trash. Instead, they came to the MILL. Ferrante believed Lewiston, and Maine, were not yet ready to see them. Then why keep them at all if they still bring pain?

"We're trying to collect the amazing community spirit that came together after such a horrible tragedy but also, unfortunately, part of the horrific events of that night," she explained. "And we don't necessarily need to display them now, and maybe not any time soon, but it is important to keep them because if we don't, then they're just lost forever."

The museum and its director had taken on the unenviable task of being the outlet in Greater Lewiston/Auburn for its people to grieve and heal through art, whether arranged by Ferrante's people or collected from the hundreds of others who added to the memorials.

How are Lewiston's students doing?

Earlier that week, across town, Jake Langlais opened the front door to Lewiston High School and welcomed me inside. He knows about helping others work through emotion.

Langlais is superintendent of Lewiston Public Schools, Maine's second largest district that is rapidly growing.

One year after the shooting, had the students and staff been afforded the opportunity to fully process the associated grief?

"I think the real answer is no," Langlais answered. "Not because they couldn't or because they just haven't but because I think there's a real question out there about, 'How do you process?'"

Since October, he and his staff had been meeting all 5,776 students where they were at emotionally and mentally.

"Man, people are still hurting. We have to acknowledge that," Langlais exhaled while sitting with me in the school's cafeteria. "How you do that, I don't always know, but I know that a lot of us are trying to do that. We're not gonna bury this thing and act like it didn't happen. It did happen. And everyone's story from that day, no matter what the level of trauma was or the immediate: What did their eyes see? What did their ears hear? What did their body feel? We can't dismiss any of it. It was a terrible day for everybody."

Langlais is not alone in his work.

Jason Fuller is as Lewiston as it gets. He's spent his whole life here, was a science teacher here, and had been the high school's athletic director for 20 years when we spoke with him during a freshman football game.

On Nov. 1, 2023, exactly one week after the shooting, we had stood in the same spot and met with him hours before Lewiston and Auburn's Edward Little high schools played their annual football game.

Due in large part to Fuller's efforts, though he refuses to take much credit, the packed stands and surrounding grounds honored dozens upon dozens of first responders and medical staff in person. There was a fly-over, and music legend James Taylor walked out to midfield and sang the national anthem.

For many people from the two cities separated only by the Androscoggin River, it was the perfect distraction from the emptiness they felt, if only for a few hours.

"I kind of lived a fairytale life when I was here as a student, and I always felt like this was my way to give back to the community and help someone else out," Fuller choked up speaking about his role. "It's been a year, and I still struggle when I talk about the community and the pain I think we all felt that day."

"I think it's really important to acknowledge that we're doing fine. We're not OK, and that's alright," Langlais explained. "But we're gonna continue to work at it to get to a place where we are much better off. But to bury it and act like everyone should be fine, I think, would be a mistake."

Whether through sports, or art, or a conversation in a hallway, Lewiston is not moving on but moving forward into the next year together.