PORTLAND, Maine — Thousands of people who are legally living Maine are prevented from working because of a federal law. They are asylum seekers.

According to the United Nations, asylum is a form of protection. It allows people to stay in the United States instead of being deported to a country where they fear persecution or harm. But those people must apply for asylum. If the government grants them that status, they get protection and the legal right to stay in the United States.

One challenge they face, however, is that the federal government requires applicants to wait 180 days or roughly six months before they are legally allowed to work, and they must apply for that permission to work, which is called “work authorization.” Furthermore, that 180-day clock doesn't start until the government receives the first application.

The United States Custom and Immigration Services often takes much longer than 180 days to approve these applications. The government website noted that 80 percent of applications are processed in 12 months.

In addition, the USCIS is struggling to process the initial asylum applications. US Customs and Immigration Services is supposed to process the asylum application within 30 days, but it often takes much longer.

The agency declined to do an interview with NEWS CENTER Maine.

Maine's congressional delegation has noticed.

"We need a far better process for adjudicating these cases. It takes way too long,” Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, said in November during an interview. “The asylum seekers want to work. They don't want to be dependent. they want to provide for their families and employers are desperate for more employees."

Collins and Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-Maine, both introduced their own pieces of legislation that would chop that work authorization waiting period from 180 days to 30. Neither of those bills made it to a vote when Congress’s session ended in December.

“Many of the people who come here to seek asylum, are highly skilled, can have all kinds of things they could be doing in our state, and frankly, they want to pay their own bills,” Pingree said in an interview in October.

"To me, this just makes common sense,” Collins said.

These restrictions pain people like Lorlette, a woman who is legally living in Maine and was granted asylum status after fleeing her home country of the Democratic Republic of Congo. She said she left because of violence and persecution.

“It's difficult because you have other needs you cannot meet because you do not have money,” Lorlette said. "I can't buy a car. I can't save for my future, my future education, but I cannot. I cannot do it."

This issue leads to a domino effect. No work means no money. No money means they cannot pay for a place to live, so they go on general assistance, taking money from city budgets to help those in need, and that money still often does not cover all their needs.

"It certainly makes no sense that they are in a situation of dependency which puts a great strain on municipal budgets to support them,” Collins said.

Some end up in homeless shelters. As recently as October 2022, 25 people seeking asylum were listed in shelters in the city of Portland.

The issue of asylum seekers entering the country is getting fresh attention in the new year. President Joe Biden made his first visit to the southern border on Jan. 8, when he announced changes that the U.S. would turn away those who do not legally apply for asylum to enter the country.

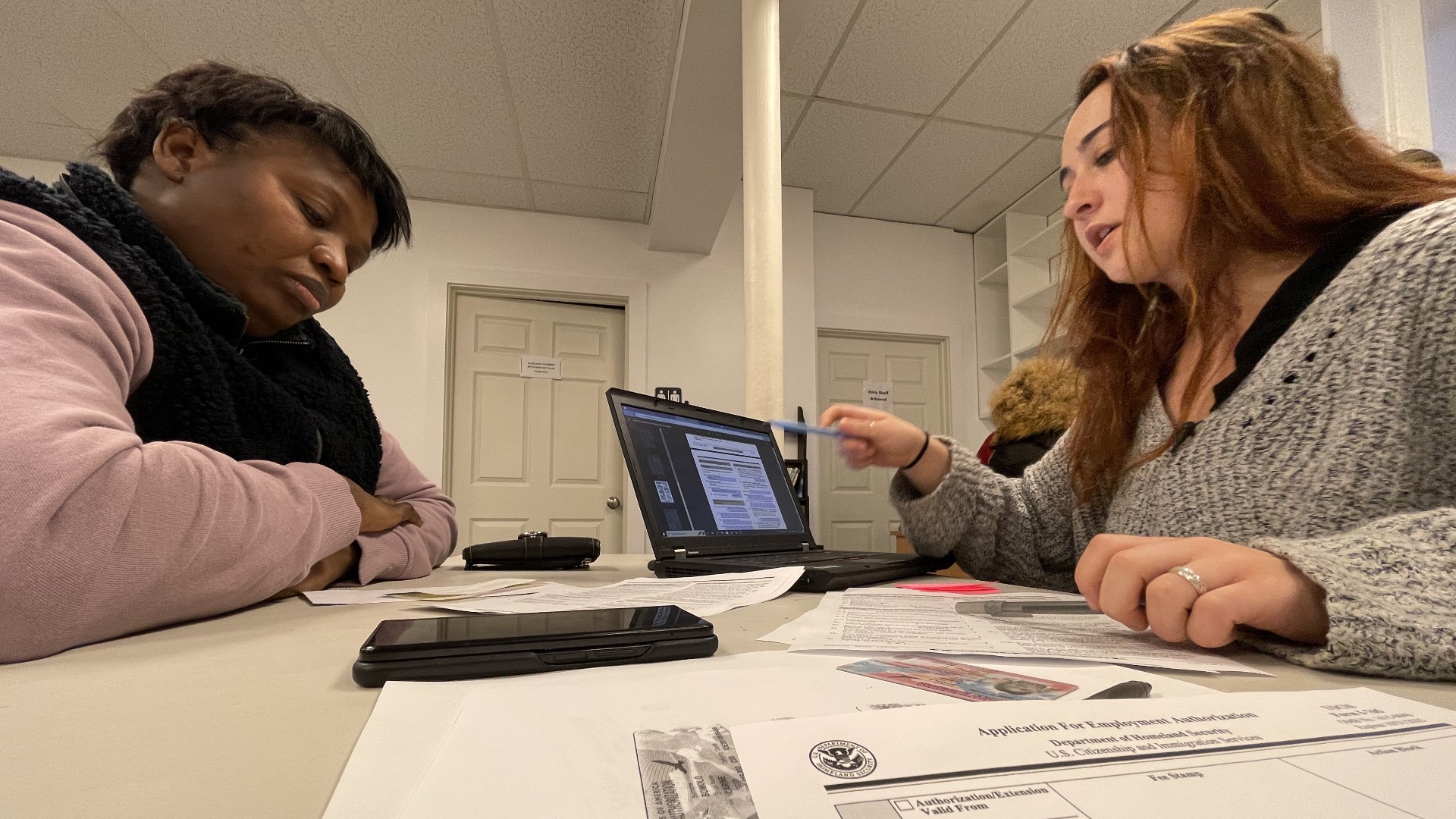

The organization Hope Acts helps people seeking asylum and work authorization fill out their government forms, to ensure simple mistakes, such as entering personal information in an incorrect box, does not delay government adjudication of their applications.

"If you've ever filled out any type of government document, it's hard enough when you speak the language fluently,” Grier Miskell, a volunteer at Hope Acts, said. “It makes you realize how challenging it is with the language barrier included trying to figure out a complex document that also has pretty high stakes.”

After 17 months in the U.S., Lorlette now has her work permit. She said she would start a new job in a few weeks.

"I felt peace. I felt free. I felt independent. I felt happiness inside me,” she said. "I will do something for help people, do something in the society, in the community for helping people, take care of people. [I will] work for the new society because the society helped me a lot."