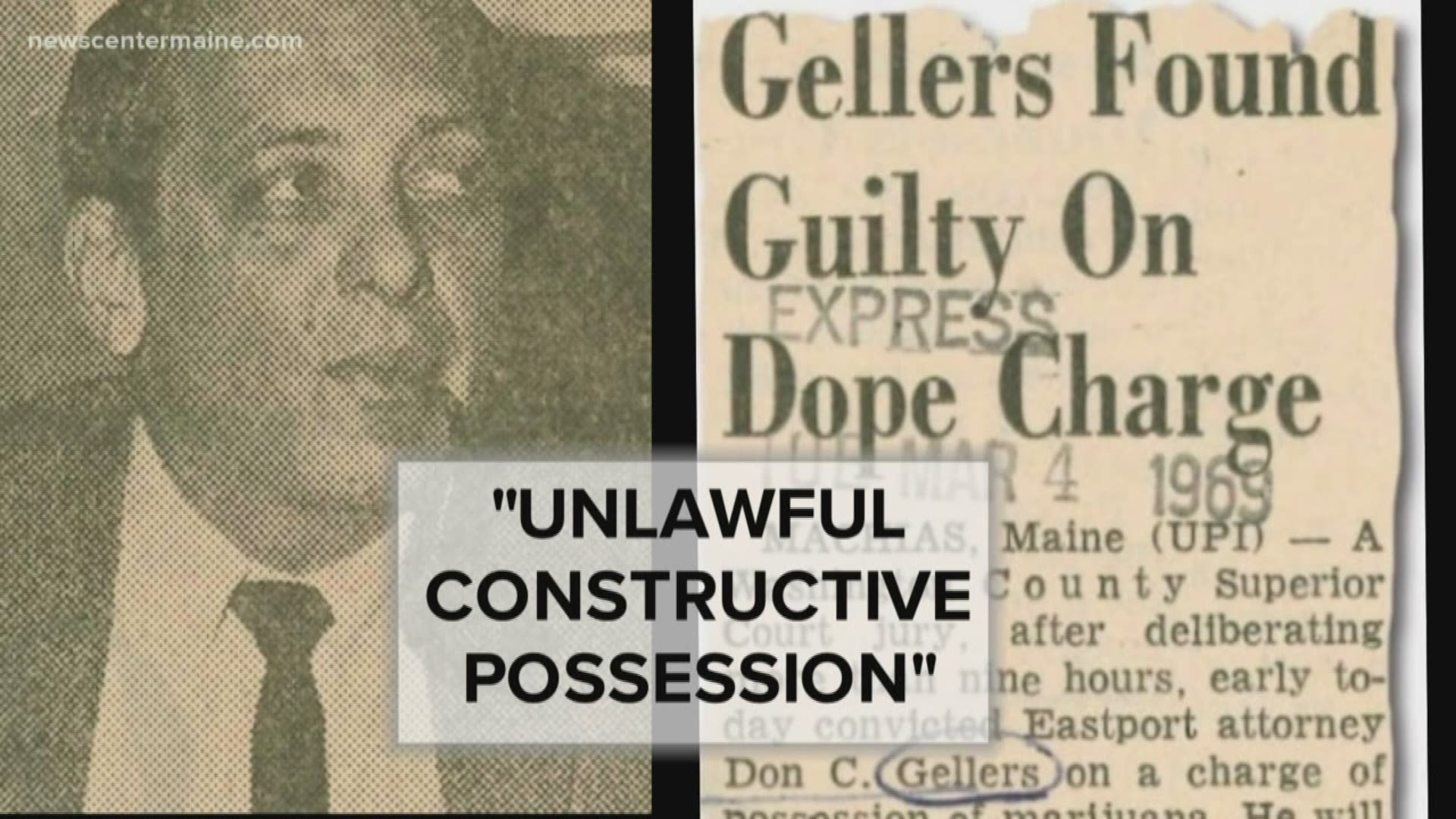

AUGUSTA, Maine — On Tuesday, Governor Janet Mills issued a posthumous pardon for Donald Gellers’ 1969 conviction for the constructive possession of six marijuana cigarettes. The pardon is believed to be the first in Maine history. Gellers is a deceased former attorney and advocate for the Passamaquoddy Tribe.

Although it's been 50 years, Gov. Mills said, in this case, "the passage of times does not diminish the need to act."

“Pardons are given in recognition of the extraordinary things people have done with their personal and professional lives, especially since the time of their conviction; but how they have improved their own life; and how they have contributed to the lives of others. During those many years between his conviction in 1969 and his death in 2014, Mr. Gellers gave much to others... For his tireless efforts to help others the whole of his life -- both for his eight years in Maine and the 35 years since his conviction -- I pardon Mr. Gellers,” Gov. Mills said.

“While this pardon cannot undo the many adverse consequences that this conviction had upon Mr. Gellers’ life, it can bestow formal forgiveness for his violation of law and remove the stigma of that conviction,” Gov. Mills said.

Gov. Mills said in her speech that research by the Law and Legislative Reference Library was unable to identify any other posthumous pardons in Maine.

Gellers represented the Native American tribal leaders and members who, "could not find counsel elsewhere during a time of great prejudice and discrimination; a time when few if any others were willing to help the tribal members with their legal problems," Gov. Mills said. "[He] worked tirelessly for the Native American people, often for little or no pay. He worked on issues small and large, and his work mattered."

In 1979, Mr. Gellers wrote this in a letter to friends:

I was dealing with a people [who] had known so many defeats that hope, itself, was a victory…. Before I came, Indians died of malnutrition, and burned up in their shacks. Getting arrested for anything meant getting convicted. Living meant begging the Welfare Indian Agent for groceries and clothes, having children taken from parents and placed for adoption in non-Indian homes, not voting for the Legislature or serving on juries, and [only] occasionally talking about treaty rights no one ever respected. I [helped stop] all that, and [I did] it peacefully.