Green Gold Rush: What happened to Maine's once-robust sea urchin industry?

In the '90s Maine sea urchin value was second to lobster. Then they vanished. Now those who still hold their licenses fear they're the last of a generation.

In the United States' easternmost city, you'll find Paul Cox and his crew working early on the water. In late winter, they're after a spikey, green, and otherwise inedible sea creature (besides the gonads): the green sea urchin.

Cox may be in his 60s, but he is considered on the younger side of sea urchin fishermen in Maine.

From December to March of every year, he puts on a dry suit and scuba gear and heads 40 to 60 feet under water off the coast of Eastport.

Alone and in often murky water that requires a flashlight, he scoops hundreds of pounds of sea urchin into yellow nets. His crew, Paul and Jevin, sort the urchin above water.

"I've always wanted to dive," Cox said. "Time means nothing under water. When you get down there, it's like you just began."

The time of year the water is most clear is also the coldest, around 20 degrees Fahrenheit outside and a water temperature of around 34 in early March.

Cox said he started to dive for sea urchin in the '90s, not long before the state cut off any new licenses to prospective fishermen.

After the '90s, no one could get a new sea urchin license.

Now everyone who dives for urchin is in their 60s and 70s, with little hope on the horizon for new licenses seeing how the sea urchin has lost so much of its habitat because of climate change and invasive species.

Cox said if the fishery continues to shrink it will die forever.

"If we're not our low yet, then there is nothing we can do to bring them back," Cox said.

How did the fishery become so depleted? And is there any hope for it to become profitable for the state again?

The Regulators Department of Marine Resources deals with a 'gold rush'

When Robin Alden took over the commissioner spot for the Maine Department of Marine Resources in the 1990s, she had to deal with the urchin industry when it started to boom. At that time, there was little to no regulation.

"Urchins is such an interesting case," Alden said. "It was a market driven by unexpected change. ... The fishery went up, and then it went down. And it kept going down."

Alden said before the industry took off, commercial fishermen in Maine viewed urchin as a bothersome bycatch.

"No one had any science on urchins," Alden said.

But the industry quickly skyrocketed to the second most valuable industry behind lobster. It brought in $35 million alone in 1995, according to the Department of Marine Resources.

Hundreds of divers and draggers were registering new licenses, with no regulation on the number of urchin you could catch.

"It was very contentious," Alden said. "A lot of dealers opposed any kind of regulation at all. ... Some people who wanted regulations didn't dare say so."

And with all of the catch going to Japan and China, it was a recipe for overfishing, seeing how there were no regulations on who could fish and how much urchin they could drag or dive.

"What the state did to regulate urchins was sensible. It just came way too late," Alden said. "We had people coming from all over the world to fish for urchin in Maine."

Alden said one thing that made it challenging to regulate sea urchin was the DMR had limited powers in the '90s.

It wasn't until legislative changes in Maine after the sea urchin industry collapsed, that the DMR could regulate a species before it was overfished.

"Back then it was still novel in Maine to limit the number of people in the industry," Alden said.

Although regulations came late, they still came. A big question Alden has after serving as the DMR commissioner is why the urchins still haven't rebounded 20 years since regulation.

"All those measures didn't allow them to rebuild, and the question is why?"

The Dealers Capitalizing on the gold rush: first in, last out

Atchan Tamaki came to the Maine in the late '80s to work in a restaurant.

Originally from Japan, Tamaki started selling Maine lobster back to his hometown of Nara.

"My friend opened up a Japanese restaurant in Portland here. ... He and his coworkers asked me to come help," he said.

Tamaki said one night after a late shift, he was walking by the wharf in downtown Portland when he noticed children throwing what looked like rocks against a wall.

When he approached the rocks, he realized it was sea urchin.

"Maybe I could do business with sea urchin," he said.

Soon he opened a processing plant.

Tamaki claims he is the first person to process Maine sea urchin and sell.

He also said he will most likely be the last one if no new licenses are proposed by the DMR or the state legislature.

"The first one and the last one," he said while laughing. "All my customers tell me not to quit."

Atchan runs ISF Trading Co in Portland.

"Business was good until 1996 or '97, and then that's when it slowed down ... because of the regulations, tough regulations," Tamaki said.

Still, more than 20 years later, ISF is one of the few remaining sea urchin processing plants in the state. A walk through the facility in a late winter morning and its evidence is a symphony of shells smashing.

Workers, many of them from migrant families, find work processing the gonads from the urchin, also known as uni.

"It's getting less and less," Atchan Tamaki said. "In any business, if you are not making money you have to close."

Tamaki said while the urchin processing plant looks busy at face value, the days they bring fresh uni in to be harvested are becoming more scarce.

"Eventually its going to be gone if they keep doing it like this," Tamaki said.

The lack of new licenses and the depleting source of fishermen willing to fish in their 60s and 70s has Tamaki uncertain about the future.

"Eventually Maine sea urchin will be gone. If there are no harvesters there, and then we don't know. We just cannot process," Tamaki said. "It's a tough lesson but ... whatever happened, happened."

Tamaki said farming sea urchin may be the future. But aquaculture for sea urchin isn't as advanced the same way kelp and oyster farming has become in Maine.

"Fishermen always have to find a way," Tamaki said. "As long as sea urchin is here, I am still doing."

The Future Could farming urchin save the fishery?

Steve Eddy knows farming sea urchin alone cannot replace the international demand of the wild fishery, but he certainly believes it can supplement it.

"I do not see it as ever replacing the fishery simply because of the scale," Eddy said.

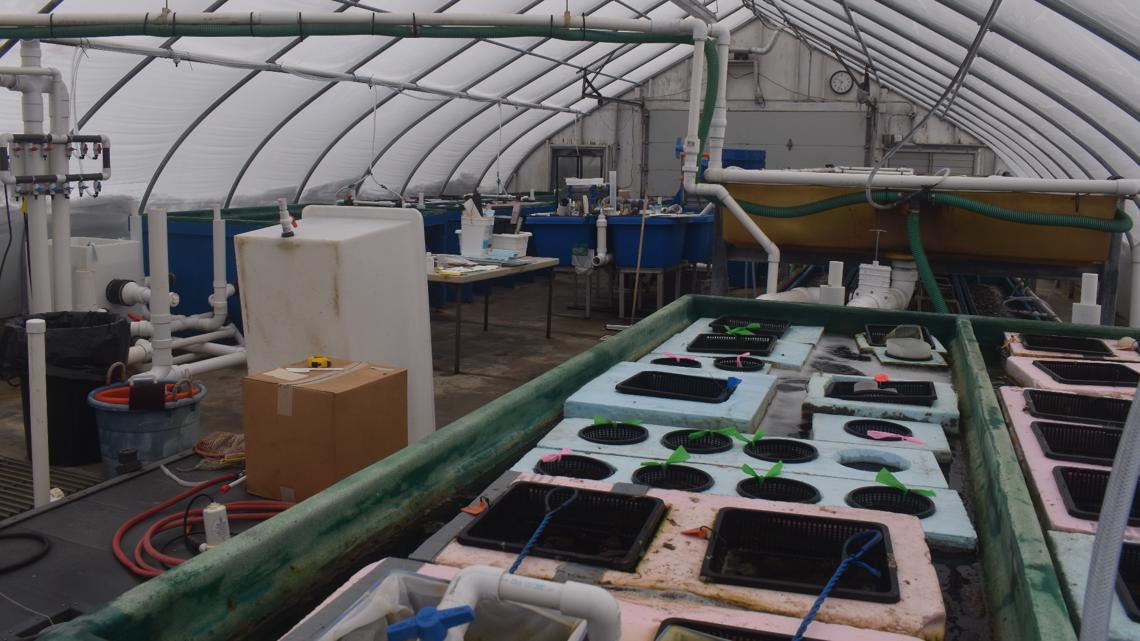

Eddy works with the University of Maine Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research. He said the future for the industry depends on the wild fishery surviving, with some aid from farming urchin.

But warming waters and competition from invasive species may keep that from happening.

"Their comfort zone is from zero to around 18 degrees centigrade ... once it gets warmer than that they don't do too well," Eddy said.

In Casco Bay, where sea urchins once covered the sea floor, summer water temps often times exceed the threshold for urchin to live.

There is also the issue of marketing farmed sea urchin to processors around the country.

"Most processors that I've talked to are biased against farmed sea urchin," Eddy said.

He said there is a preference for the "wild caught" label that sells well in international markets.

When talking about invasive species, green crabs are No. 1 for the destruction of sea urchin, which have been known to eat the native species.

Eddy said farming sea urchin can still hold a huge key, such as introducing farmed sea urchin into wild kelp beds.

"[In the future] I see a lot of young people involved, and I see aquaculture part of the mix," Eddy said. "I see more than 2 million pounds of landings a year."

But as sea urchin farming continues to grow, the survival of the industry is all dependent on the number of fishermen willing to harvest urchin as they continue to age and die off.

"Hopefully that will be addressed before it's too late. As long as the resource is there the state will open the door up to new licenses or license transfers," Eddy said. "The traditional industry as we know it will not survive without the fishery."

Eastport: the last frontier Fishermen make their case to protect their work

Paul Cox said at some point soon, new licenses will either have to be given out, or fishermen should be allowed to hand their licenses to their children.

"But I don't think it's time right now. We're doing well to hang on right now," Cox said.

While in his 60s, Cox said he is confident to continue diving in Cobscook Bay. But he's worried for fishermen much older than him who still have licenses.

"They're dying off; I hate to say it," Cox said. "We're losing a lot of good fishermen every year."

He says two to three fishermen he knows die each year.

"It's kind of sad to see where it was to now, for sure."

As Cox and his crew box up the urchin and send it shipping to southern Maine, the worry for the future continues.

"Put your money in the wild fishery," Cox said. "I think we're at our low, and if we're not at our low, then there's nothing we can do to bring them back because we've lost the fishermen."

He remains hopeful there will be an answer.

"I think there are positive things. ... We've got some lessons to learn, but I think we're going to come ahead."

He drives off in his pickup, cash in hand. Another season finished in what remains of Maine's once prolific sea urchin industry.

And with limited options for solutions, it's literally a race against the clock for these aging Maine fishermen.