MADAWASKA, Maine —

Editor's note: Scroll to the bottom of this page for part 2 of the video

People who lived in parts of the St. John Valley more than 200 years ago, grew up speaking French. That’s because before Maine became a state, much of this land was part of New Brunswick.

In 1785, 16 French-Acadian families settled in what is now part of northern Maine. They settled on both sides of the St. John River after being driven from their homes by British soldiers.

Before roads, bridges, and railroads, the river unified communities, commerce, and culture. Within a few years, more than 200 families lived there, most French and Catholic, and they traveled to the provinces of Quebec and New Brunswick for supplies.

Maine became a state in 1820, but establishing the St. John River as the international boundary took another 22 years. That decision divided the French-Acadian population into what were essentially two nations, two languages, and two ways of life.

“We are talking about an entire population of French-speaking people who are now in Maine,” said Lise Pelletier, historian and director of the Acadian Archives at the University of Maine in Fort Kent. “They are Americans.”

Over the years, despite strong familial, linguistic, and cultural ties, that divide deepened. The push in Maine to become fully Americanized was strong, and a 1919 law banning the use of the French language in all but foreign language classes solidified it.

"It's not just a figment of people's imagination. I mean, there was a law that was passed here at [the Maine State House in Augusta] that people couldn't speak French because ... racism, and that's never going to be right,” Maine Senate President Troy Jackson, of Allagash, said. “The lost generation is people like myself that never had French spoken to them because it was frowned upon so, therefore, I don't speak French and my parents don't either.”

What Happened

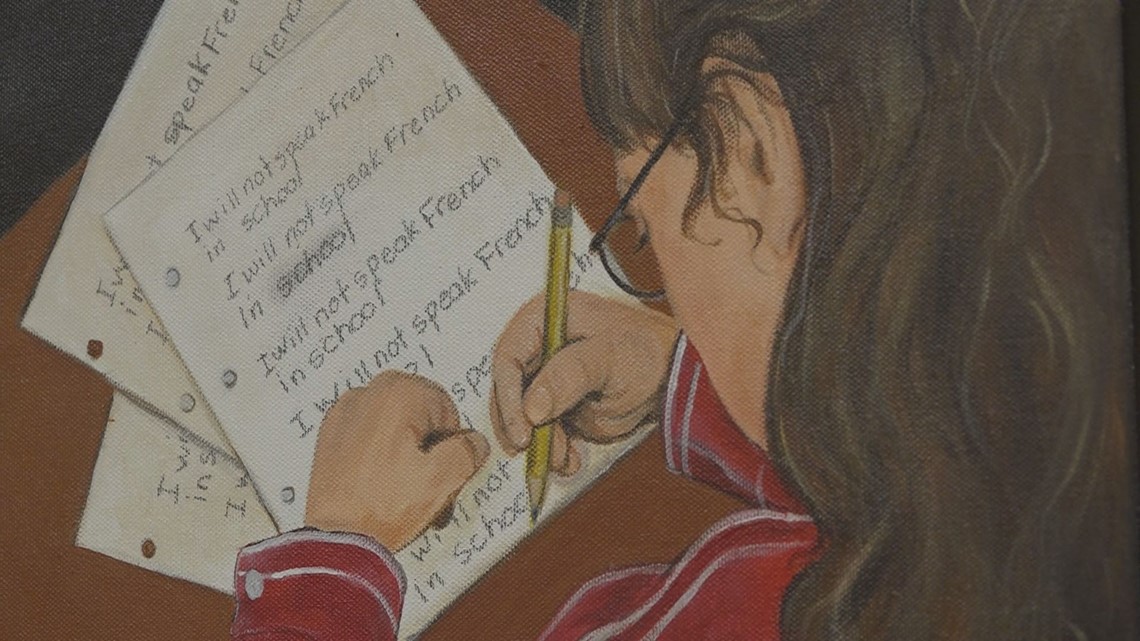

Many Mainers who grew up hearing French spoken at home remember being punished for speaking it with friends on the school playground. Word was that if schools didn’t obey the law, their state funding would be in jeopardy.

"Here you have children playing outside all together, their mother tongue is French, and they can't speak French,” said Lisa Michaud, coordinator for community engagement for the Franco-American programs at the University of Maine.

Michaud said her great grandparents only spoke French, her grandparents spoke French and very little English, her parents spoke French and English, her own generation also spoke French and English and now her daughter speaks mostly English and very little French. Michaud knows the language may be gone by the time her daughter has kids.

“I was told that the French that I was speaking was not the correct French, so what does that do to a young child starting school?” she said. “I said, 'Well, I am not speaking it then.’”

"It was basically put by the English who were responsible for the great deportation of the Acadians [that] we were seen as second-rate citizens, and when we came here to Maine, we were treated as such, even in the 30s and 40s,” said Cur Soucy, professor of Advanced Placement French at Madawaska High School. "My generation, we lived through a very oppressive time where we were not allowed to speak French. So, in terms of your own ego, you're seen as an inferior individual."

"I didn't speak French to my children because I did not want them to go through what I went through," retired Frenchville Superintendent Lisa Bernier said.

Reinforcing the “No French” law, the Ku Klux Klan maintained a significant presence in the state, inspiring such fear in French-Acadian Catholics that some changed their last names to be more American.

“It was feared that because the number of French who were decedents of the French-Canadians, who had emigrated to Maine … it was feared that their number could upset the political status if they revolted and demanded to be part of a union, better wages, better work conditions … they could easily upset the status quo,” Pelletier said. “They burned crosses, they elected a governor, and [the state of Maine] had the largest number of members in the United States for a while, far surpassing the states of Alabama and Mississippi.”

Fearing prejudice and punishment, French-Acadian families stopped handing down the French language to their children. Pelletier said the loss “took people’s heritage away from them.

For many years, Jacques LaPointe, a Franciscan Roman Catholic priest and an author of Acadian history, was a priest at different churches in the St. John Valley. LaPointe said that when the French language and culture were oppressed in public, “the church became a bastion for the French culture because that was one place where you could basically express yourself as a Franco-Acadian.”

“The church was not part of that, but there was someone there to tell them, 'Be proud of who you are,' and as Acadians … they continued to be able to practice their faith in French," he said.

In 1960, 41 years after it was enacted, the “No French” law was repealed. But by then, the French language and culture were all but gone from the St. John Valley.

Today, none of the public elementary schools in the St. John Valley have a full-time French program. Structured French programs don’t start until middle school, and there only three French teachers. Two of them live in Canada and drive across the border to teach students in Aroostook County.

Despite the benefits, without enough teachers and with student enrollment declining, language arts and math classes took priority when budgets were cut, and French classes were trimmed. Today one part-time teacher rotates among three elementary schools in the district that encompasses Madawaska, Fort Kent, and St. Agatha-Frenchville.

“As our student enrollment decreases, we can’t keep adding staff. Staffing is quite expensive in a school budget,” assistant superintendent Gisele Dionne said. "We are not teaching math in French, or science in French. We used to ... in the mid- to late-90s we had an immersion program at the elementary level, and that was quite successful. However, it disappeared with lack of funding.”

Rebuilding Language in Schools

Dionne said she would love to return French to the early grades, in part for better brain development but also to refocus on the culture and heritage of which residents are so proud.

"It's my goal to teach them to speak French for them to be able to communicate with others," Debbie Nadeau, one of the three middle school French teachers, said.

But dropping enrollment has Dionne worried about the future of French in the valley.

“If this trend continues, I am very worried because how can you keep offering all the electives at high school that students may need or may desire when you don’t have enough students justifying all the staff?" she said.

Jackson said he has proposed legislation in the past to return French to the curriculum, but said, "Unfortunately in Maine, we have a very strong local control aspect for education and so that doesn’t always go over well in mandating this into the entire educational community."

Soucy worries, too. He remembers graduating from college in 1975 with 35 others who majored in French. In the past two years, not a single graduate of the University of Maine in Fort Kent or in Presque Isle has majored in French.

While the St. John Valley still contains the highest percentage of French-speakers in Maine, that figure has declined dramatically. In 1950, 14 percent of Mainers called French their native tongue, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2019, only 3 percent of Mainers spoke French at home.

"I'm 68 years old,” Soucy said. “I'm not going to be here forever, and right now I think that there's a major concern that the pot is empty.”

Soucy encourages his students to practice and speak French outside of class. He also teaches them French-Acadian history.

He hopes the language could be revived at the university level, where students recommit themselves to second languages, but he’s not sure what to do in the valley overall, other than to hope “as a dad, and my wife as a mom, that we have entrenched in our own kids those core values.”

The loss of language and lack of a structured program in elementary schools “sends a message that the language is not as valued as much as math, or science, or English,” Pelletier said. “The language connects us to our identity and to others that share that identity as well."

Rebuilding the Heritage

But a number of organizations are working hard to return the Franco-Acadian culture and heritage to northern Maine.

L'Association Francaise de la Vallee du Haut-St-Jean has started a new kindergarten in Frenchville and has enrolled 25 students so far in an afterschool French class. The group hopes to increase immersion programs in the area.

“We see our French dying, and we know that children learn languages very quickly, and so we felt it was important to do something to preserve the language and the culture in our community,” said Nancy Dionne, director for the French Youth programs for the St. John Valley.

Noah Ouellette of the French consulate in Boston said the embassy could help buy materials in French to teach and help sponsor staff to attend trainings in French.

“We also have a program for them to get a scholarship to fund a native French-speaking intern to come to their school for the whole year to work as a teaching assistant,” he said. But for that to happen, the school already needs to have a solid French immersion program in place.

Ouellette said Louisiana has developed successful immersion programs in schools, where more than 30 percent of the classes are taught in French, including courses like math and social studies.

“It really helped bring back French, which was dying out in Louisiana, and we want to create a similar dynamic in Maine,” he said.

The University of Maine offers a minor in Franco-American studies, the only university in the country to do so.

UMaine's Franco-American center also publishes "Le Forum," the oldest bilingual journal in the U.S., every three months. The journal is by and about Franco-Americans in the northeast and highlights events and initiatives for everyone to take part in.

The Acadian Archives at UMaine in Fort Kent hosts classes, programs, and activities all year to celebrate and enrich the culture in the area.

But these efforts face obstacles, not least of which is the stigma associated with the language, instilled in Franco-Americans over generations.

“Older people feel shy and are reluctant of practicing the French they are learning in school,” Dionne said. “They are worried about mispronunciation things, or not saying it correctly.”

“Even something as simple as having Acadia Day here at the Legislature brings any stigma that is still left … out,” Jackson said.

And English dominates television, social media, and daily interactions in northern Maine, reducing opportunities for practicing French.

Adding to it all, interactions across the U.S.-Canadian border are notably more difficult than they were previously, in particular since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and, more recently, since the coronavirus pandemic, which closed the border.

Still, LaPointe believes the French culture and identity in Maine remains strong, “even at times stronger than on the other side. The language, though, is stronger on the Canadian side.”

He said those with French-Acadian heritage must understand and be proud of who they are and where they came from, and Maine schools, municipalities, and other entities must celebrate and recognize the rich heritage.

"We are not less American because we recognize that we have roots that come from elsewhere,” he said. He's writing a book “to stress the beauty of the Franco-American culture, and the heritage, and not to lose it, so that’s my personal way of doing it.”

LaPointe said efforts to return the language and culture to the people of the St. John Valley will be worth the effort.

“There is a sacredness about life that they have, and they hold on to, that it’s beautiful," she said. “It’s expressed in a different way than it was in 1919, but there’s that duality that I think it’s very well focused, and that serves the Acadians in the Valley very well. The identity? There’s a pride to being Acadian. At times much stronger … than there is on the other side.”