BIDDEFORD, Maine — UPDATE: Students and faculty from University of New England along with the University of Maine and Unity College planted dozens of trees on June 12 in Orono. The team is planting 100 trees in two days and more in July.

Professor Thomas Klak is a man with a mission.

"We need to reinstill this knowledge in our culture of how important the American chestnut tree is to the eastern United States, and we’re going to do it," Klak said as he sat in front of three bags of American chestnut seeds from wild specimens in Maine.

The professor of environmental studies has been working to speed breed American chestnut seedlings for the last year. He has seedlings in the greenhouse on the Biddeford campus of the University of New England and in a special growth chamber that looks like a huge white refrigerator.

In the early 1900s, a fungal blight from Asia was brought to America, presumably accidentally, when smaller Asian chestnut trees were imported. The Asian chestnuts were immune to the fungal blight, but the American chestnuts could not have been more vulnerable.

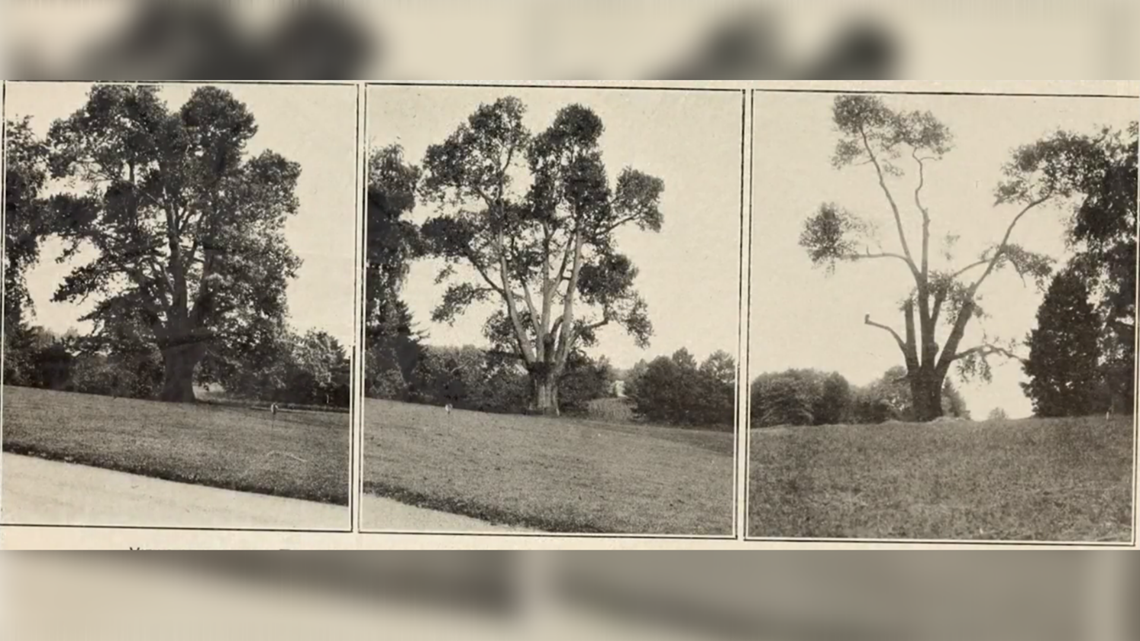

Klak said, from 1904 when the blight was first detected at the Botanical Gardens in the Bronx until 1950, the once prolific tree that grew from Maine to Alabama and as far west as Indiana was wiped out. Four billion trees were killed.

"Whole villages went belly up when the blight came through," Klak said. The massive American chestnut tree, nicknamed the redwood of the East, was a staple in American culture, featured in songs and paintings. The tree also had a profound ecological and economic value.

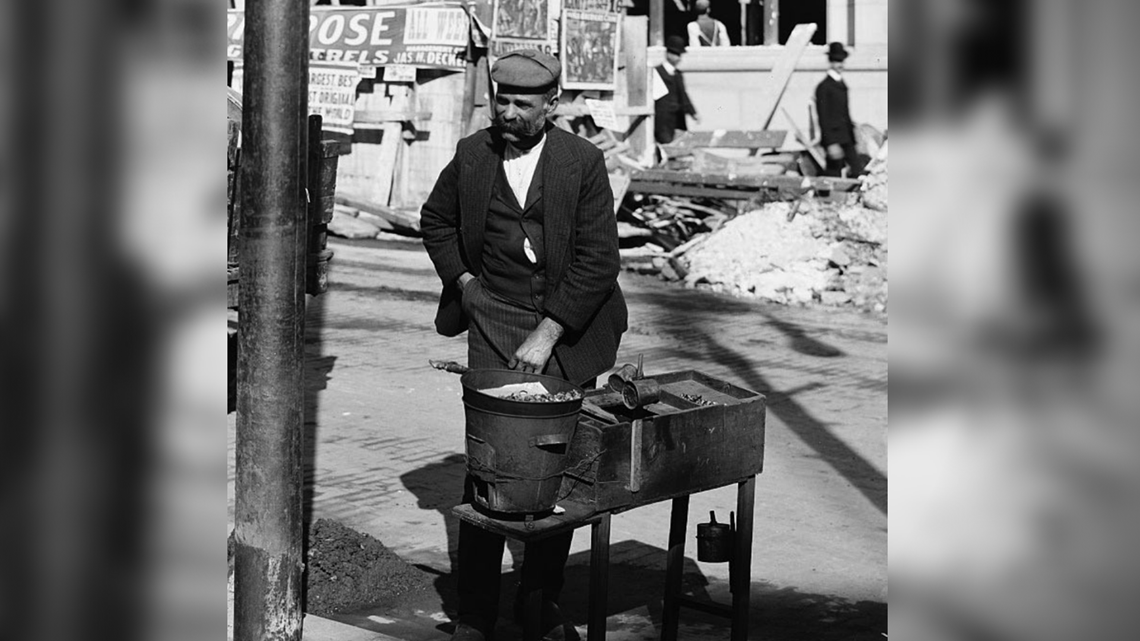

The tannins in the wood made it rot-resistant. Growing over 100 feet tall and the tree's size made it valuable for everything from buildings and furniture to utility poles. It was common to see vendors roasting chestnuts on the streets of big cities like Boston, Philadelphia and Detroit . According to Klak, chestnuts are highly nutritious and delicious.

Klak has partnered with State University of New York (SUNY) and is speed breeding particular seedlings that have a wheat gene inserted into them to protect them from the fungal blight.

Although stray American chestnuts can still be found here and there across the U.S. (Maine has the tallest one in the nation), it is considered functionally extinct because it cannot reproduce as it normally would. SUNY and UNE are using biotechnology to create the new blight-resistant tree. But time in an obstacle to those efforts. It takes mother nature 10 to 15 years to grow an American chestnut tree to the point that it is sexually mature, which is when it starts to create pollen that can produce more trees.

Professor Klak does not want to wait that long.

So he and his students have been exposing their wheat gene seedlings to intense light in their growth chamber and in the greenhouse as they try to mimic peak summertime sunlight, temperatures, and humidity which are favorable to quick growth. And they have been able to do it.

In November, the team spotted the first nodules of pollen on seedlings as young as 9 months old. They are the second institution and the only one in New England to be able to do it. Klak and his students are now collecting the pollen with the wheat gene and freezing it as they wait for approval from the USDA. If permitted, they will cross the pollen created in the lab with wild trees in Maine as they try to bring back the species.

"This is the biggest ecological reversal we'll be able to achieve," Klak said. "To restore ... a keystone for species of the eastern forest and to bring it back to the rightful place on the landscape. It’s a big deal."

*The American Chestnut tree's diameter can be in excess of 12 feet.