ORONO, Maine — Maine is the most forested state in the nation and those woods provide a rich habitat for many species of animals but studying them can be a challenge. One Ph.D. candidate, Bryn Evans, has been tackling that challenge for the past four years using an arsenal of motion-triggered cameras.

"Nothing beats seeing an animal with your own eyes," Evans said.

But what might be a strong second is the more than 800,000 images of wildlife Evans has captured at her 197 sites across the state, that span from the Allagash to Paris.

Evans is a student in the Department of Wildlife Fisheries and Conservation Biology. The 32-year-old has been working with her advisor, Dr. Alessio Mortelliti, and in collaboration with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIFW) on her research.

"Graduate work is very draining," she explained, but Evans' work is one that she finds incredibly fulfilling.

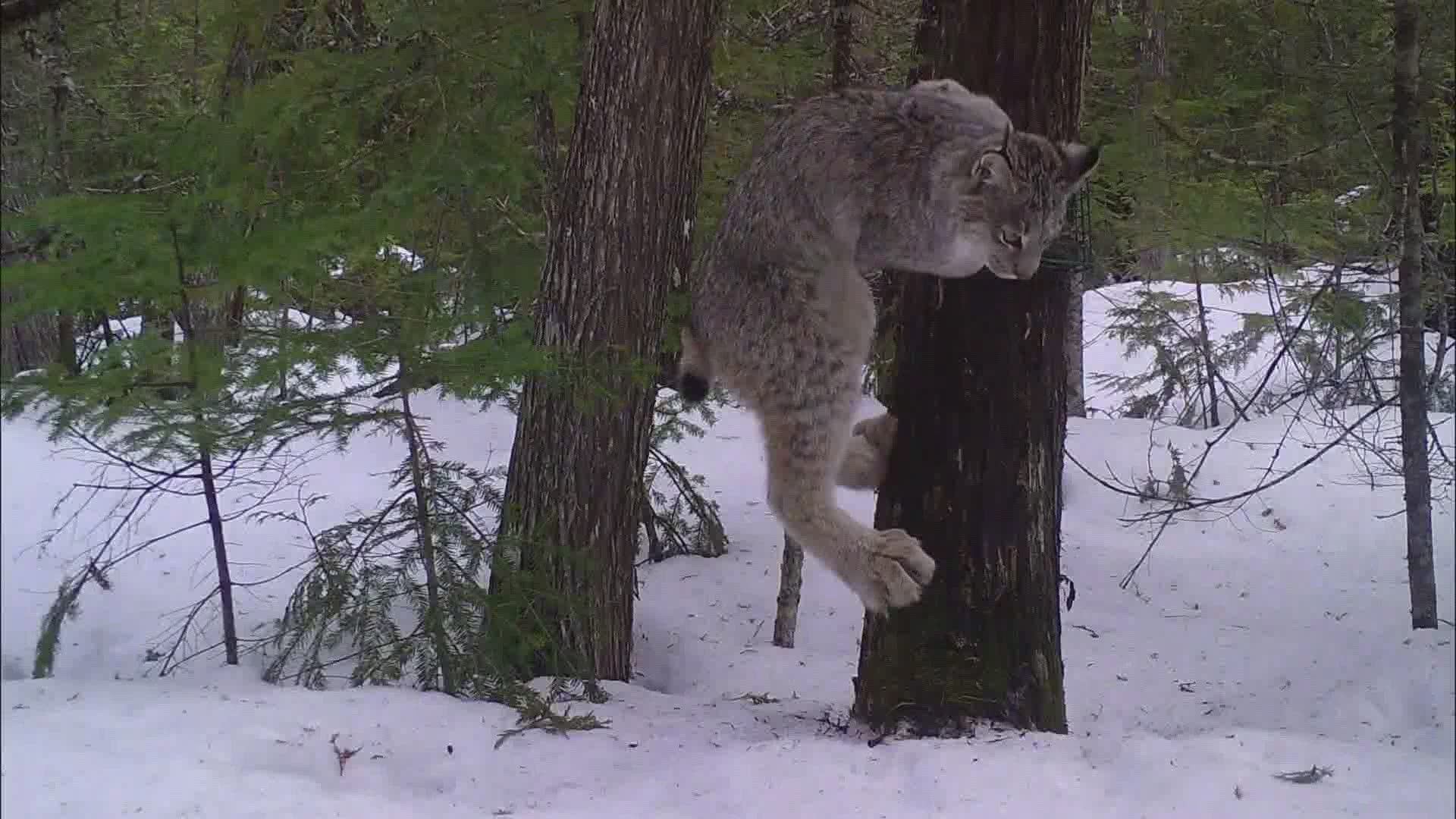

She has 120 camera traps—motion-triggered cameras that snap pictures when animals wander perfectly into view. And she ensures that they do by using a small piece of beaver meat to lure medium-sized carnivores in front of her cameras. The cameras are left out at her nearly 200 sites for two weeks to a month before she retrieves them. Many of her sites cannot be reached by car so she has to snowmobile, snowshoe, or hike to them depending on the season.

Evans admits she started using camera-traps or trail cameras as an ancillary tool but found they could provide a lot of data for relatively low effort. And camera traps are not invasive, as opposed to radio collars which show a lot of information about one specific animal but require researchers to capture animals and often stress them out in the process.

The research started because the Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife wanted a long-term, large-scale cost-effective way to monitor primarily fishers and martens, and so that is where Evans' research has been focused. She said there have been concerns that the intensity of the timber harvest industry might be causing a decline in suitable habitats for marten and fishers.

One thing her research has shown thus far is that despite how these species segregate in other places in the U.S., in Maine marten and fisher are coexisting in the same habitats at the same time.

"[There] doesn't seem to be an avoidance pattern going on which is really interesting to me," Evans said.

She wonders if the habitat in Maine plays a role in this overlap and if it's sustainable. Evans doesn't have answers yet but the data she's collected is serving as a jumping-off point for her dissertation.

Although her research is focused on marten and fisher, the cameras don't discriminate and they snap pictures of other species including lynx, weasels, hares, bears, coyotes, deer, moose, and others. Those pictures and the data that it provides about other species are not going to waste but being utilized by MDIFW and other students' research.

Evans' work is not finished yet. She hopes to capture 1 million images by the time she is done and hopes her work continues long after she graduates, which is planned for December 2021. MDIFW is currently considering continuing her research for another 25 years to look at long-term trends of Maine wildlife.