PORTLAND, Maine — Senator George Mitchell’s life has been the classic success story of the American Dream.

His father, Mitchell has often said, was the orphaned son of Irish immigrants, his mother an immigrant from Lebanon. That poor family in Waterville, however, raised a son who would become one of the most powerful and respected leaders in America.

It helped Mitchell earn a lasting place in the history of Northern Ireland.

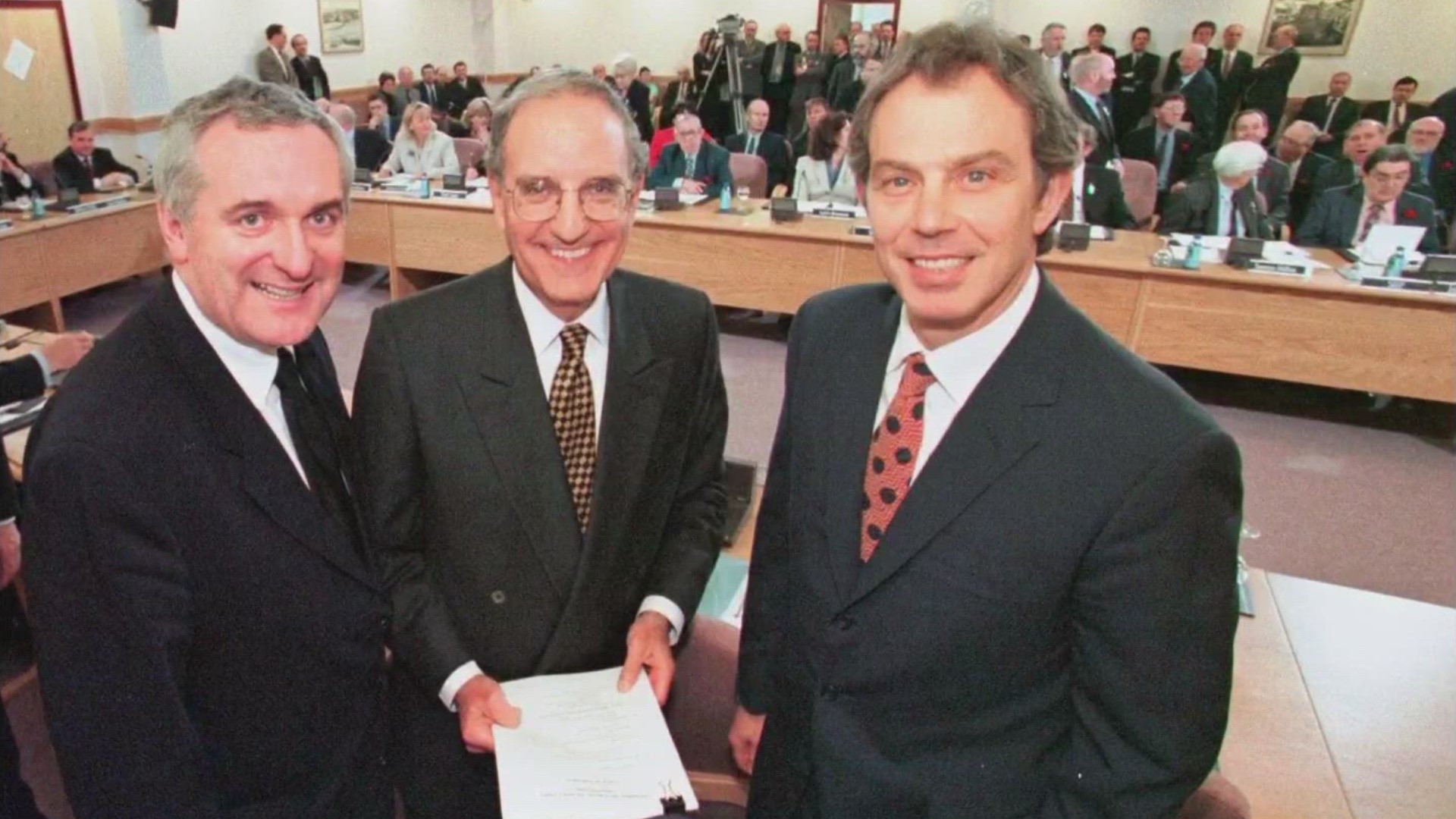

In 1998, after more than two years of difficult back-and-forth talks, Mitchell was able to negotiate a peace agreement among the many factions that had been waging a bloody and destructive battle in the province for decades.

"It was a very difficult and dangerous place," Mitchell recalled during a recent interview from Florida. "I think the most meaningful statistic comes from the... Northern Ireland police services. In the 245 years before the peace agreement, in political violence in Northern Ireland, 3,500 people were killed and over 50,000 injured, many of them brutally and totally impaired for life. In the 25 years since the agreement, there have been a total of 155 deaths."

Mitchell described the negotiations as difficult and often frustrating.

"For most of the two years, there was very little progress. These leaders had lived their whole lives in conflict. They didn’t listen to one another, very insulting, a lot of disorder."

Mitchell said his patience and willingness to let everyone say what they had to say helped keep the communication lines open. But in late 1997, he said he began to despair of reaching a settlement.

"We had been in talks, then a violent episode, then a series of retaliatory killings. So the killings and bombings that had been largely reduced flared up and it looked like the process was coming to an end, and the violence would be back."

Mitchell then told the various factions he wanted to set a deadline, to force them to reach an agreement or go home.

That step, he said, finally moved the process ahead.

"And when they all agreed to the deadline, I knew they were serious," Mitchell explained.

During that time, the senator faced his own personal challenge, when his wife was about the give birth to their first child. Mitchell flew back to the U.S. for the birth and considered not returning to Northern Ireland—but quickly changed his mind.

"I asked my assistant to find out how many children were born in Northern Ireland that day. And they came back quickly and said 61 children were born in Northern Ireland on that same day my son Andrew was born. So I told my wife I was thinking about leaving [the talks] because as every parent knows when you have a child, your responsibilities change. And she said, 'No, you go back. I’ll take care of Andrew, you worry about those 61 kids.' And I went back and a few months later, we were able to get an agreement."

That was Good Friday, April 10, 1998. The agreements became known as the Good Friday Accords, and they are still in place for 25 years, holding the factions in Northern Ireland mostly together in allowing the elected government to settle differences without resorting to guns and bombs.

"It's an agreement some of them had trouble accepting. It was very difficult for some of them, difficult for all because in any compromise, you get some things and the other side gets some things too. But they didn’t want to go back to violence—that was the powerful driving force."

Mitchell said he’s been worried about the impact of the "Brexit" discussions for Britain and the United Kingdom to withdraw from the European Union because that threatens the open border between Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK, and the Republic of Ireland, which will remain part of the EU.

An open border between the two was a key goal of the peace accords.

He said the various interests are talking and negotiating the issue, but in the interim, the Northern Ireland Assembly, its elected government body, has been shut down. Mitchell said the government needs to get back to business, and hopes that can soon happen as part of the negotiations over Brexit.

Mitchell said the people of Northern Ireland deserve a hopeful future and have been able to have that for most of the past 25 years, despite occasional flare-ups.

When asked if the peace agreements have a lesson to teach the world, the senator quickly said they do.

"Despite deep hostility, despite political violence, despite many people being killed or injured, permanently impaired, despite 800 years of negative history, the people of Northern Ireland were able to reach an agreement to resolve their difference by democratic and peaceful means. And if they can do it there, anybody can do it in their own society and their own country. it takes determination and, most of all takes political leaders with courage and strength and vision."

Sen. Mitchell, who will turn 90 later this year, plans to deliver a speech at the 25th anniversary celebration in Northern Ireland on April 17.