LAMOINE, Maine — For young women growing up in the 1960s, the only "appropriate" athletics were tennis, cheerleading, and in some communities, golfing.

Robin Emery was not having it.

"You might get your internal organs all messed up, or you will grow a mustache," Emery recalled people thinking. "My mother would say, 'You are going to get all stringy.'"

Emery was born in 1946 in Bangor, but grew up in Windber, Pennsylvania, and spent summers at the family home in Lamoine every year with her parents and brother. She loved Maine, in part because of the neighborhood boys who lived around her with whom she spent summer nights playing baseball until dark.

"I played with the boys. I ran with the boys. I did everything with the boys. And then you become a teenager and people say, 'Girls don't do that kind of stuff,' and that was really hard for me," she said. Emery is turning 75 next month and she's still annoyed that she missed out on playing Little League and hockey.

"I would have loved to play hockey or women's rugby," she said. "Can you imagine?"

Since 1972, Title IX has required schools to allow women to participate in sports, but long before then, Emery was chasing athletic opportunities on her own. It started in 1967 when she was in Lamoine on summer vacation from college.

"I walked a lot but it just took too long," Emery remembered. In deck shoes, with wool socks, Bermuda shorts, and a blouse, Emery ran the four-mile loop around her Lamoine home without stopping.

"I made it around one time and I never looked back," she said.

Her mother griped that all the running was unhealthy but Emery couldn't stop. It simply "felt too good," she said.

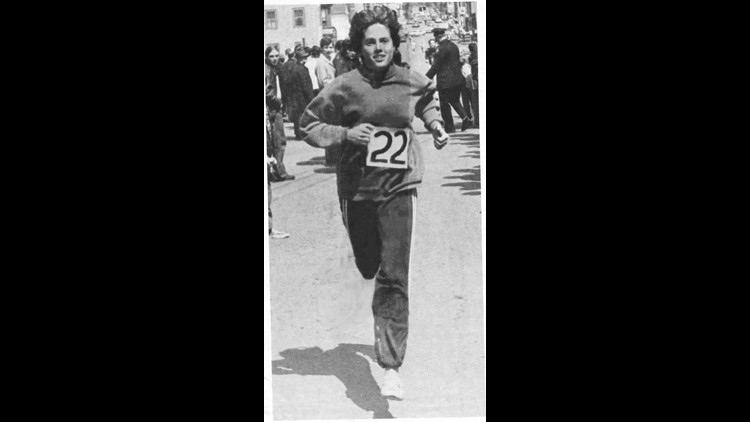

While at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, Emery wore oversized hooded sweatshirts to disguise herself and would run in graveyards to avoid attracting unwanted taunts from men in passing cars and even the occasional empty beer bottles they threw at her. One day, coming down a hill on her way toward her dorm, something miraculous happened.

"All of the sudden I started to fly ... It was the runner's high. I felt so good. I said, 'This is it. I'm not going to stop.'" Fifty-four years later, Emery is still chasing that feeling.

By 1972, after honing her skills on her own, Emery was ready to compete. She and Diane Fournier became the first two women to run in the Boys Club 5 Miler in Portland, the state's oldest road race. Their applications were rejected at first, but with the help of Dick Goodie, who championed female running in Maine, Emery not only ran but won the race with a time of 33:04. She has won that race 9 times.

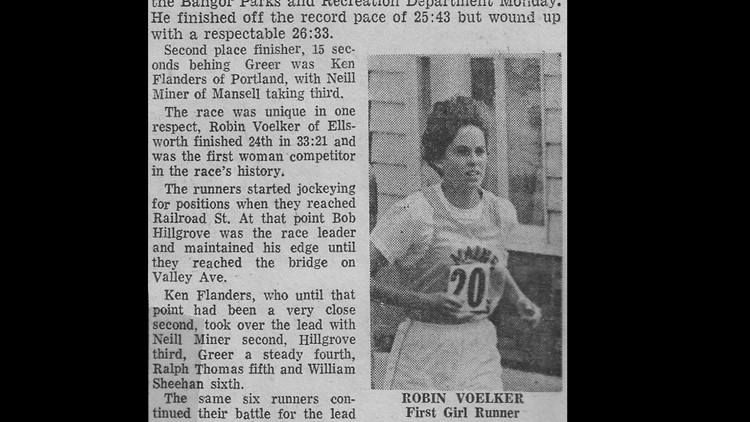

On Labor Day in 1972, Emery entered the Bangor Labor Day Five Miler. The officials told her she could run as long as she stayed out of everyone's way. Emery finished 24th out of 44 and would later go on to win the Bangor Labor Day Five Miler more than a dozen times.

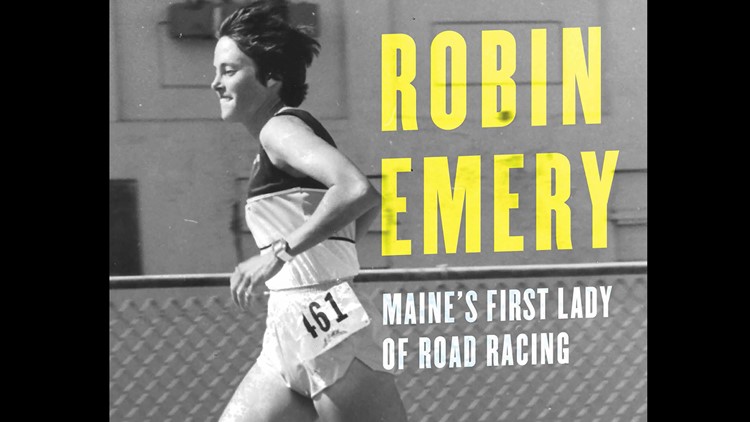

Beginning in 1972 through the mid-80s, Emery won more than 250 road races in Maine, many of them as the first female runner. Ed Rice wrote a book about Emery's career, "Maine's First Lady of Road Racing."

"Robin's record of achievement will never be equaled by any male or female," said Rice, who first became acquainted with Emery when she blazed past him in a road race in the 70s.

While taunts from men were commonplace, Emery said Mainers, and especially the community of Lamoine, have treated her well.

"In Maine, especially rural Maine, people accept differences even if they don't agree with it," she said.

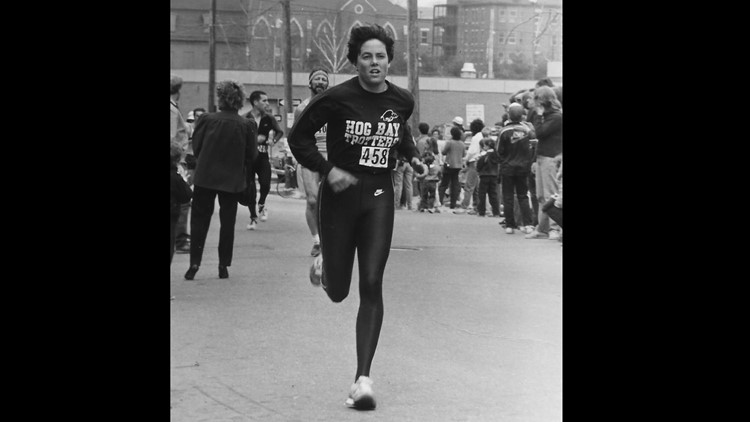

"She’ll joke and say, 'Nobody else was there. That's why I won,'" Rice said. "When these women started to come in the late 70s and early 1980s, Robin beat them head-to-head and she kept beating them."

Although only in her 30s, and despite her lack of coaching, Emery ran ten years without losing a race until Joan Benoit Samuelson came onto the scene.

Emery recalled the first time she lost to Benoit, a future Olympian.

"I was devastated," she said. "I was going to give up."

She tried to drown her sorrows by picking up the javelin but later learned to keep running despite not always winning. At 74, getting beat is still a hard pill to swallow.

"When I think ... if you had told me I'd be glad to run a 9-minute mile, I would have said you're nuts," she said with a laugh.

Robin Emery

Nowadays, Emery runs a little slower in her Nike Pegasus sneakers that are held together with glue ("I can get a whole year out of one pair," she said of the shoes she refers to as "old friends.")

In the winter, the retired school teacher who taught 53 years, mostly in Ellsworth, runs an average of 40 miles a week. In the summer she lightens her mileage because she competes most weeks in road races across the state. To ensure she has a good race, Emery follows a certain regime steeped in superstition: She always eats Lucky Charms cereal the morning of a race and never crosses the finish line before the race. Her superstitions have served her well, as she is still in good health -- despite drinking Mountain Dew daily -- and has had few injuries.

Even after all these years, this pioneer runner who attracted the attention of so many hates the limelight and still gets nervous before a race.

"I will wake up in the morning and have a sense of doom," she said. "I say to myself, 'You're not going to win. It's okay because there's faster people.'"

Emery said her nerves in her 70s are better than they used to be when she would get almost physically ill days before a race.

In September 2021, Emery was inducted into the Maine Sports Hall of Fame, an honor that Ed Rice said was long overdue. On top of her more than 250 wins, Emery also has two national championships and a 10th-place finish in the world in the cross-country masters’ division.

The rooms of her Lamoine home are lined with plaques, trophies, and medals but Emery's focus is on the next race, and the next person, in her age group, she can beat. She thinks back on her running career and wonders what might have been if she had been coached or been born a few years later, but for the most part, she's just happy that the younger generations don't have to worry about being a woman and wanting to compete.

"If you want to bad enough you can," she said. "There is really no one standing in your way."

For this humble pioneer runner, it's not about the wins, it's about the running.

"It was difficult but I still did it no matter what because it felt so good. And running was more important than just racing. I don't think I've done anything great except for show up and just run."