PORTLAND, Maine — When NEWS CENTER Maine’s Pat Callaghan traveled to the Kennedy Space Center in January of 1986 to report on the launch of the space shuttle Challenger, he did not pack winter clothes. Who takes a parka and mittens when leaving Maine for Florida?

The overnight temperatures at Cape Canaveral were freezing—literally below 32 degrees—and so was Pat in the days leading up to the launch as he stood in the outdoor press stands, where gusty winds made the cold even more biting. Shivering in a light raincoat, Pat needed warm clothes, so he and photographer Josh Bradford headed to Sears, where the selection was so poor that he ended up buying the only product he could find for his hands: a pair of gardening gloves. He was wearing them when the Challenger blew up shortly after takeoff, killing all seven members of its crew including the first teacher in space, Christa MacAuliffe of New Hampshire.

For the shuttle program, the Challenger explosion was most of all a human tragedy, but it also exposed grave problems in its culture of safety and communications. “It really threw into chaos a system at NASA that they believed was effective at doing space flight,” says Roger Launius, former NASA chief historian and contributor to the book, “NASA Space Shuttle 40th Anniversary.”

“NASA sort of had this patina of excellence about it,” Launius told me. “People believed that whatever you want to do, give NASA the job and they’ll go do it. Now that was proven incorrect and it took a lot of time to recover from that.”

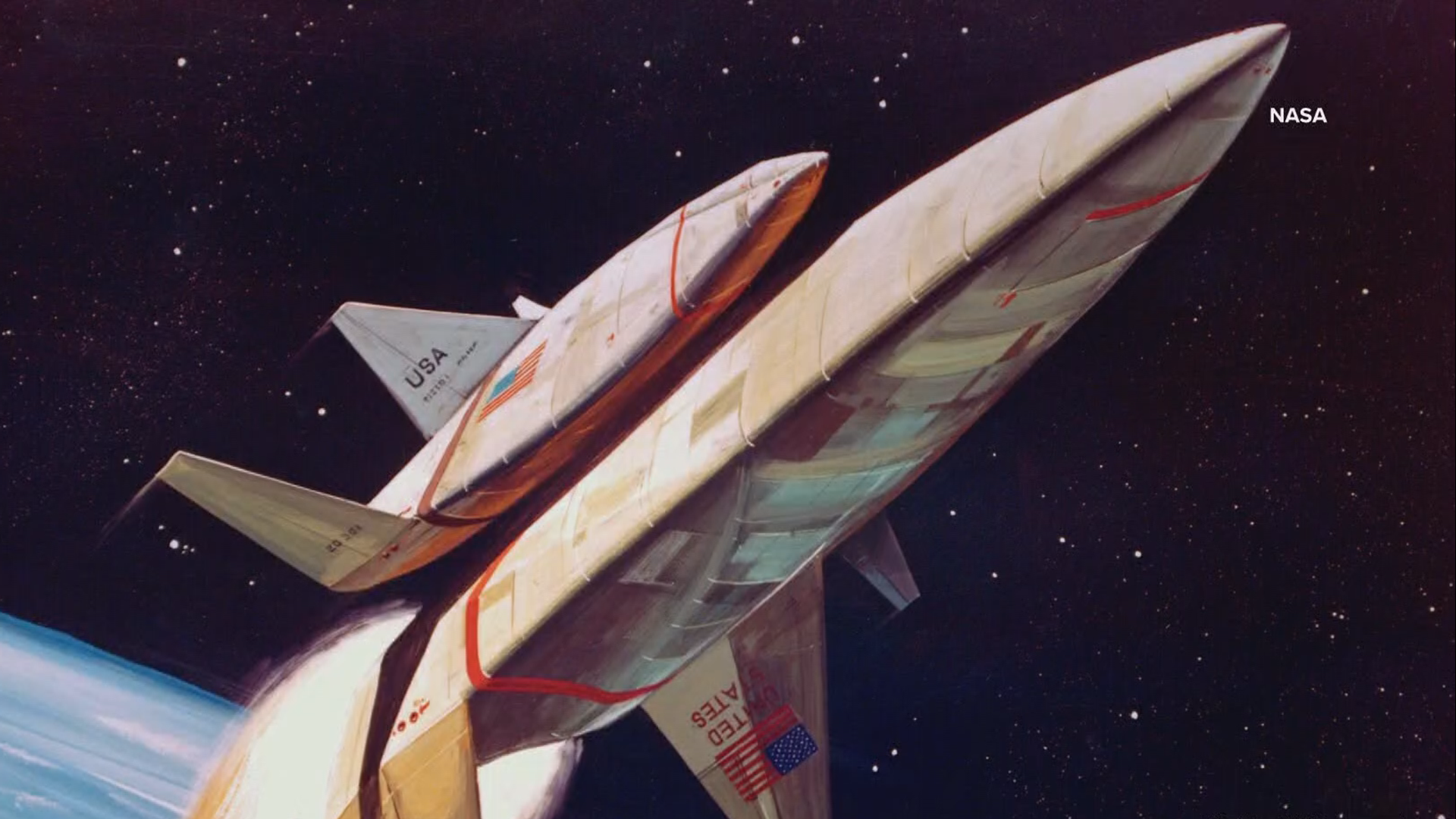

One hundred years from now, one thousand years from now, historians will be looking at the steps humans took as they began to explore space. The shuttle’s role as the first crewed, reusable spacecraft will not be forgotten. By going into space and returning, again and again, the shuttle did something extraordinary: It made space flight routine.