ORONO, Maine — When Maraina Miles spent a month doing geological research in a remote, rugged landscape in the far southern tip of Chile, it was no vacation. For starters, she and the team of about ten researchers she was part of had sunshine for only a couple of days.

“Most of the time it was rainy,” she says. “Some days it was snowing. Other days it was horizontal ice pellets.”

Miles, who is pursuing her Ph.D in geology at the University of Maine, traveled to Chile to gather evidence about the end of the ice age that began there some 20,000 years ago.

“One portion of the work was collecting rock samples…to date them, to see when a glacier was at a certain point,” she says. “From that we can tell when the ice retreated, how fast it retreated.”

The other part of the work required the crew to dig about 15 feet down to the bottom of bogs to collect organic material. “That [material] marks a time when the ice had retreated and the bog started forming and plants started growing. If we date that, we can know when the ice retreated.”

The goal of the fieldwork is to supply physical evidence that will help scientists answer some big questions about changing climate, not just millennia ago but in our own era as well. That’s why researchers travel thousands of miles to a cold, damp place at the end of a continent and spend a month under gray skies tramping through bogs and alongside glaciers.

“It’s definitely type-2 fun sometimes,” Miles says with smile. “I did lose a boot one time, and you don’t notice you’ve lost your boot until your sock is in the bog. But with the views and the places you get to go, it doesn’t matter that it feels like there’s 100 pounds of gear on your back. It’s worth it.”

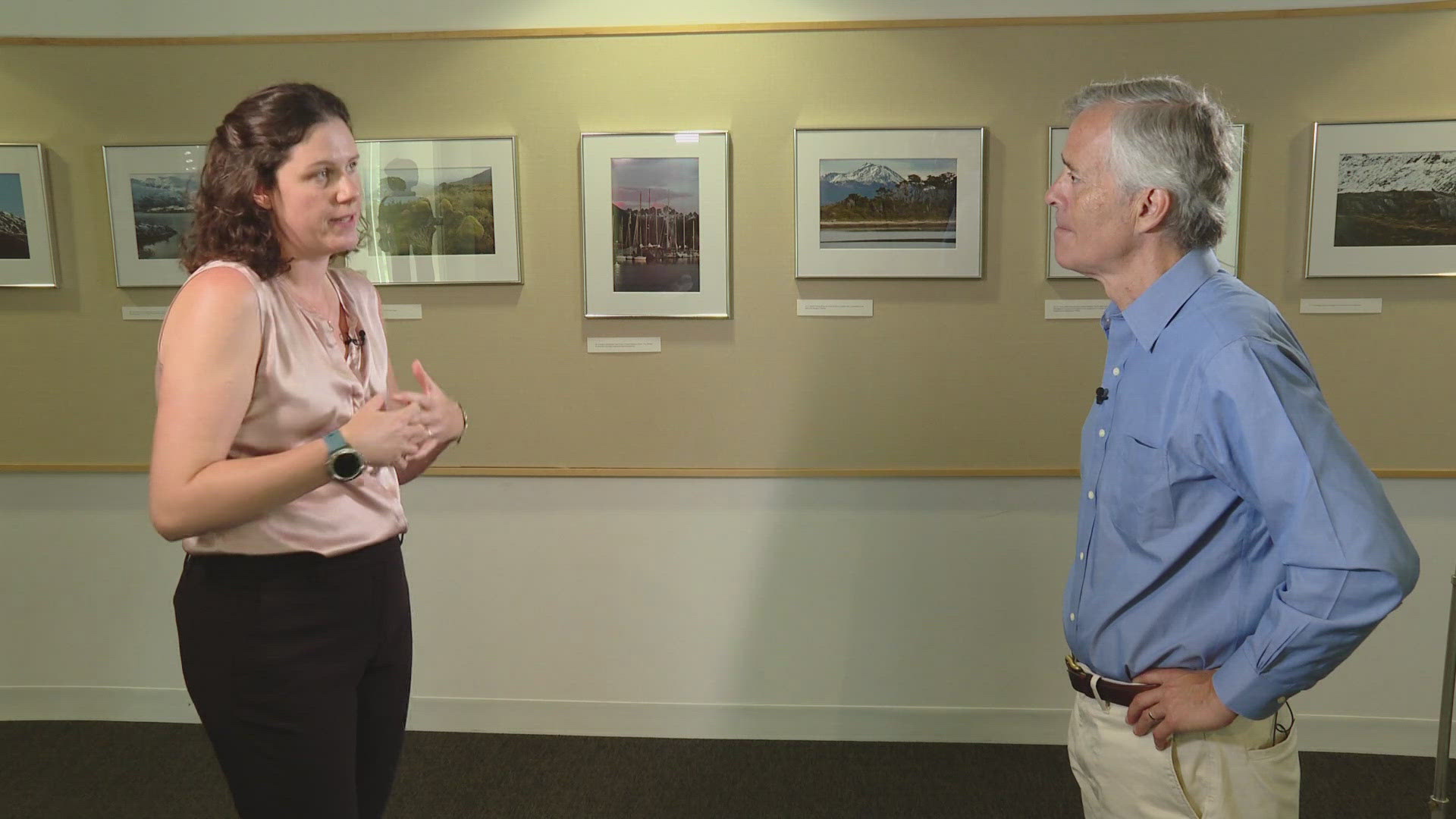

Miles took hundreds and hundreds of photos while in Chile. Some of them are on display at the Hudson Museum on the UMaine campus in Orono until the start of the fall semester.