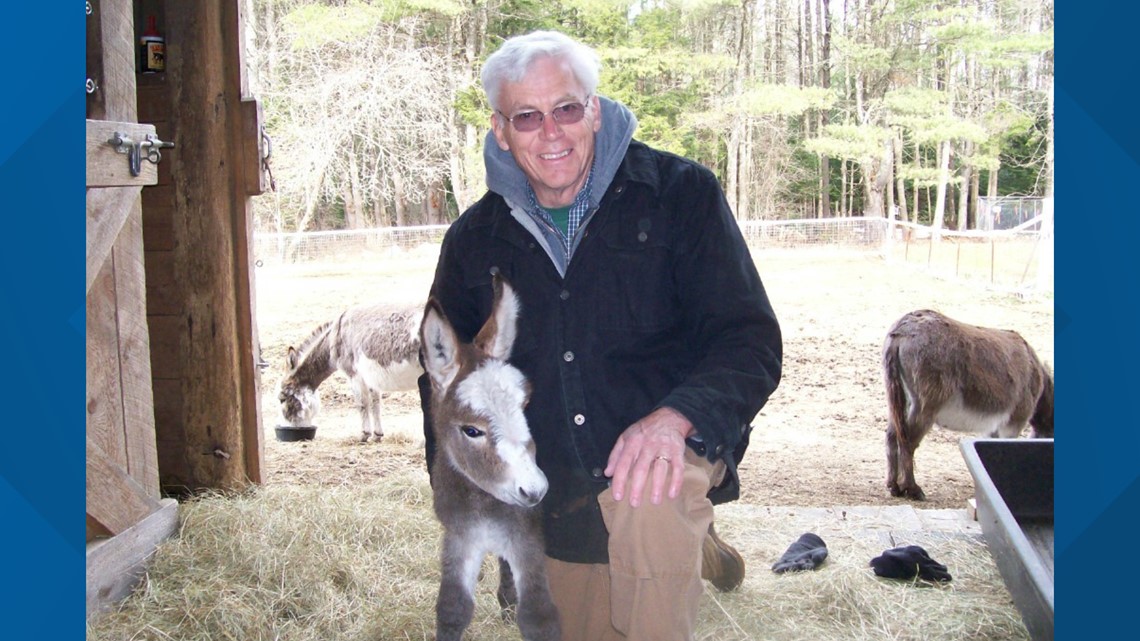

WINDHAM, Maine — Dr. David Jefferson is a horse veterinarian who has practiced in the state for more than 50 years.

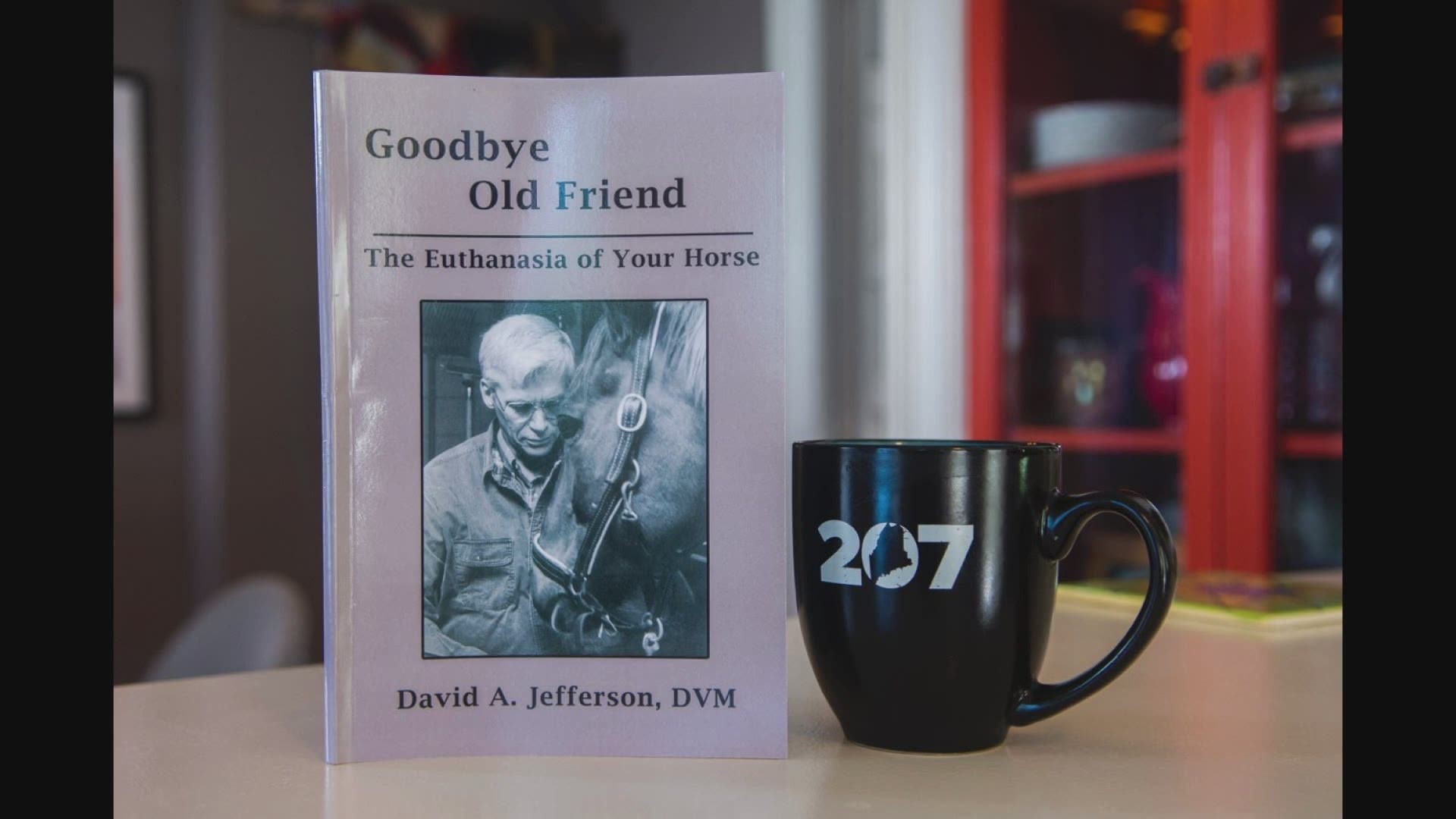

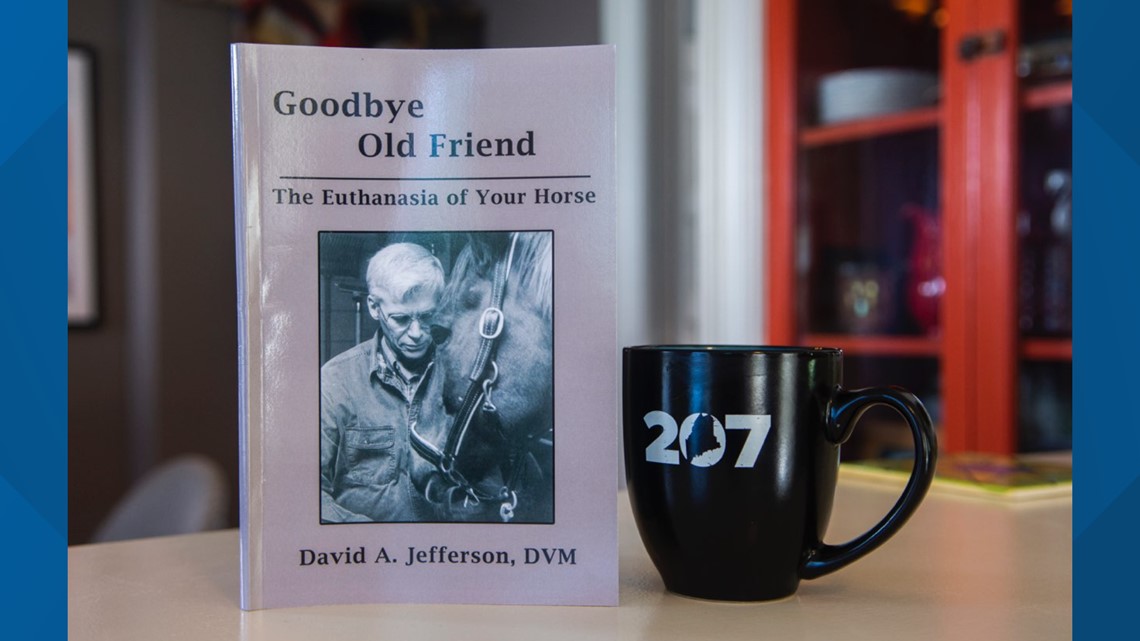

Back in 2017, he wrote a book called Maine Horse Doctor: On The Road with Dr. J, which chronicled his career.

While speaking to groups about that book, the same questions kept coming up from horse owners. How do I handle the end-of-life decisions for my horse?

Finding little practical information on the topic, Jefferson set out to write a book on the topic.

207’s Peggy Keyser sat down with him at the Maine State Society for the Protection of Animals where, over the years, he has ministered to the horses and served on their board.

The title of the book came easily. At breakfast one morning, he told his friends he planned to write a book about equine euthanasia. Without hesitation, a friend suggested he call it “Goodbye Old Friend.”

"In every talk I gave, the questions would come up. 'I have a question about euthanasia.' 'How do we…I have trouble with that.' 'How do I, how do you handle that. How do I handle the emotions about that.' All kinds of questions. And that was four years ago," he recalls.

The book speaks to the intense bond between horse and owner and details the practical aspects of the process – what actually happens when the vet comes to put a horse down – as well as the overwhelming grief that horse owners experience.

"Goodbye Old Friend" is dedicated to anyone who takes on the "responsibility of horse ownership with the knowledge that you will probably outlive your horse – and someday have to make an end-of-life decision for them."

These conversations are important.

"A decision to put a horse down is a joint decision – it’s the owner, veterinarian, and family that’s involved. And the timing of it. When they’re domesticated, they just get weaker and weaker, and pretty soon they get so they have trouble standing up. And getting up from down. And so, that’s when we start to think about this," Jefferson said.

The heartache of making the decision of when to end an animal’s life is well-known to any pet owner.

With horses, that decision feels bigger – simply given the size of the horse.

Domesticated horses rarely die a natural death but rather succumb to conditions that become challenging to heal.

"One of the common ailments of horses is colic, so they need, some horses need abdominal surgery which is a huge undertaking. And very, very expensive. And when a horse reaches a certain age it becomes not a good thing to do. All those things enter into the decision. Into the process of making a decision."

Leg fractures are also difficult for some horses to heal from.

"In virtually all cases, it’s a decision that it’s time for it. And usually well thought out ahead of time. It’s a release. A lot of people call it the final gift. It’s the last nice thing you can do to an animal. The timing is critical, critical."

After a career that spanned five decades, Jefferson wants to prepare horse owners for this time in their horse's life.

"I think I wanted them to be aware of the whole process because so many times we come to that decision, it’s their first horse, they’ve never had a horse put down. You can tell that they’re nervous. 'What do we do? What happens. I want to know what happens.' And so I wanted to have that resource out there that people could go to a book and say, 'Oh, this is the way the process happens. This is what I can expect,'" Jefferson said.

Each chapter starts and finishes with a quote about horses – the joy of horse ownership and the impact of losing a horse.

"Here’s one I like, by Linda Lipshutz. ‘We should never underestimate the powerful draw of a bond with a being that loves us unconditionally asking very little in return. Using this comfort and source of joy can be incomprehensible.’"

"People are very attached to their horses," Jefferson said.

The grief of losing a horse extends beyond just the owner. Jefferson learned the other horses in the barn experience their own sense of loss.

"If a horse is just taken out of a barn and never seen again, the horse that is left is, 'Where is my friend. Where is my friend?' Because they form very strong bonds. And in this particular case, the owner asked that the horse – she knew that the horse would be frantic that was left behind. So she said, 'Can I bring the horse down to say goodbye?' And I thought, 'Well? OK – we can try that.' And it was really something because they will smell the body after the horse has laid down, they’ll smell the body … sometimes pick up a leg and drop it, sometimes bite the horse, and then? In every case, sometimes it takes 30 seconds, sometimes 15 minutes, they accept that the horse – their friend is gone. And when they go back to the barn, we don’t hear the screaming that we did. Very amazing. So, from then on – and this happened years and years ago we always ask that every horse in the barn be brought out."

In the final chapter of the book, Jefferson writes about his own experience of putting down a horse he had in his care.

"Pat was a Belgium workhorse that somebody lent me. I’d always wanted a draft horse that I could use in the woods to pull logs out with because I burn wood at home. So I said to the owner, 'Can I borrow this guy?' and he said 'Oh, sure!' I had Pat for a long – quite a while. And then one day, Pat broke a leg. Another lesson for me because I realized then how deep this pain goes. I wished there’d been another veterinarian within 50 miles that I could have called. And I had to put the horse down myself and it was very hard, very hard."