PORTLAND, Maine — On the edge of Portland’s Munjoy Hill, overlooking Back Cove, is a small circle of standing stones. They are a memorial to one of the city’s native sons. Charlie Loring was a tough kid, raised in the Depression, who went to war twice, but never came home from his final mission.

He was one of five Loring brothers who went into the service—Charlie and two others in World War II, and younger brothers Paul and Robert during the Korean War.

Paul, now 92, looked at a photo of all five brothers and thought back over the years.

"That's in front of our house on Anderson Street when Charlie came home for Christmas."

It was shortly before Charlie headed to the Korean War—a fight from which he would never return.

Charles Loring had already been to war in Europe, flying a P-47 fighter-bomber during the Battle of the Bulge. In December 1944, he was shot down over Belgium but was able to bail out of the plane. He was captured after he hit the ground.

"And he was in the hospital for a while, then they put him in Stalag 3, I think, a prisoner of war camp," Paul Loring, the last of the five living brothers from that generation, said.

He said Charlie escaped after the guards ran away just days before Germany surrendered to end the war in Europe.

But those five months clearly left a mark, as Charlie—now a major—prepared to be sent to the Korean War five years later.

"He told my father and mother he would never become a prisoner of war again," Paul recalled.

That comment has stuck with the family over the years after Charlie Loring intentionally crashed his P-80 jet fighter into a Chinese artillery position he had been sent to attack.

Paul said pilots of the three other planes in his group said Charlie’s plane had been shot up in the initial attack.

"They all said the same thing, as witnesses, that he pulled up his plane deliberately, and he could have turned to the right and gone back to base. But he deliberately made a 45-degree turn and crashed into the Chinese artillery."

That act destroyed the artillery that had been attacking American and allied troops, saving lives on the ground at the expense of his own.

For his remarkable act of heroism and sacrifice, Major Loring was awarded the Medal of Honor, America’s highest military award, and the Air Force base in northern Maine, his home state, took his name.

Paul Loring said the family didn’t know anything about his brother’s loss for two years. Charlie, he said, was listed as missing in action because there was no chance to recover a body or wreckage, and the Air Force feared that if he had survived, any mention of his heroism could result in his death. In 1953, the family was told Charlie had died, and that he had been awarded the Medal of Honor.

When Loring Air Force Base closed in 1994, the official portrait of Major Loring and his medal were taken to Portland City Hall for display. Some years later, the family worked with the city to have the memorial built on the Eastern Prom.

Except for Paul and the family, local memories of Charlie Loring may have faded with time until earlier this year, when Paul got a phone call from two men in Belgium.

"I thought it was a scam at first," he confessed.

But he discovered the call was legitimate, and that the two men had dug up some remaining pieces of Charlie Loring’s P-47 from World War II. A small metal plate with numbers on it led to a records search that confirmed the identity of the plane.

The men in Belgium also contacted the Loring Air Museum to send the pieces to Maine.

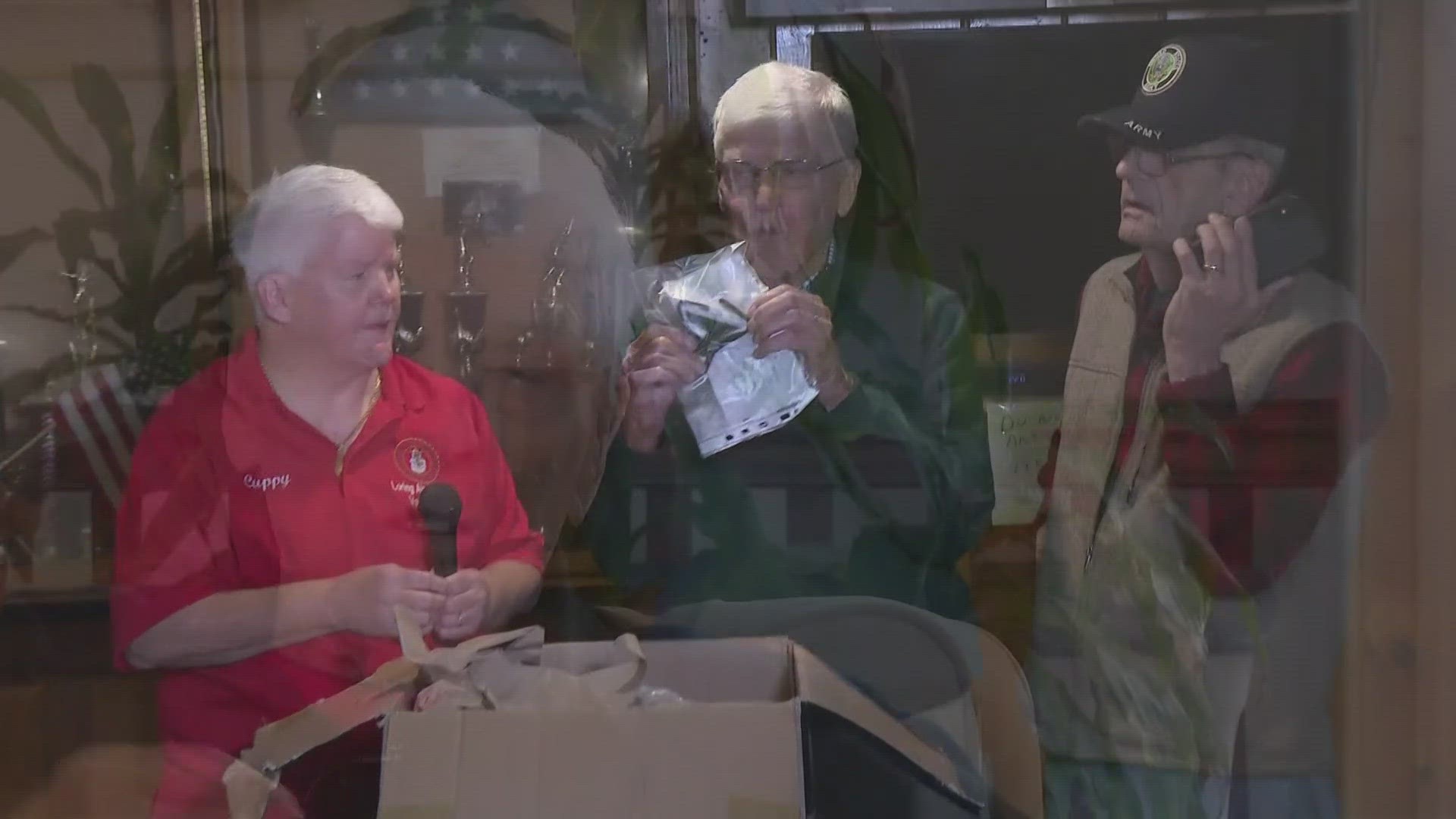

In October, Cuppy Jahndro and others from the museum brought the box from Belgium to Portland for the Loring family to open.

They gathered on a rainy Saturday at the Charles Loring AMVET’s Post on Washington Avenue, just below the hill from the Loring memorial, and not far from where he and Paul grew up.

There, Jahndro and Pasul Loring opened the box and literally reached back 79 years.

The first item removed was sealed in a plastic bag: a battered buckle, from the plane’s seat belt.

"It was a buckle to buckle him into the plane," Paul said later. "It was all busted and broken, and Cuppy said 'I want you to pull that out because that was the last thing your brother touched before he bailed out,' so I choked up a little there."

Piece by piece they pulled out several dozen metal fragments of that plane, buried under a field for nearly eight decades. Loring family members and other veterans looked on. Most of the pieces were unrecognizable, but that didn’t matter. All had been part of the machine that took Charlie Loring to his first war.

Most of the pieces were taken back to the museum in Limestone, where they will become part of the display and tribute to the base’s namesake.

"So the family has given us photos over the years, but nothing that was actually from Charles himself. This was his airplane he was proud of it and it's what put him in a prisoner of war camp," Jahndreau said.

Two pieces of the plane stayed with Paul Loring, and for the time being, will remain with the family. They are tangible, touchable reminders of the long-lost brother, a hero from Portland and from Maine, who gave his own life to protect other troops.

"A sense of closure for me," Paul said afterward. "A closure. [Those are] parts of the plane he flew."

He said they will become part of the family’s legacy, to keep Charlie Loring’s name and memory, and his story, alive.

In northern Maine, Cuppy Jahndro said the Loring Air Museum will be doing it too.