SACO, Maine — Traffic zooms steadily between Saco and Biddeford, crossing the Saco River on the Main Street bridge and the Elm Street bridge on Route 1, farther upstream.

They are separate cities, with a combined population of about 43,000, and they have a great deal in common.

But 100 years ago, the cities were split, with strong emotions on both sides of the river. They were divided by ethnicity, social status, and religion.

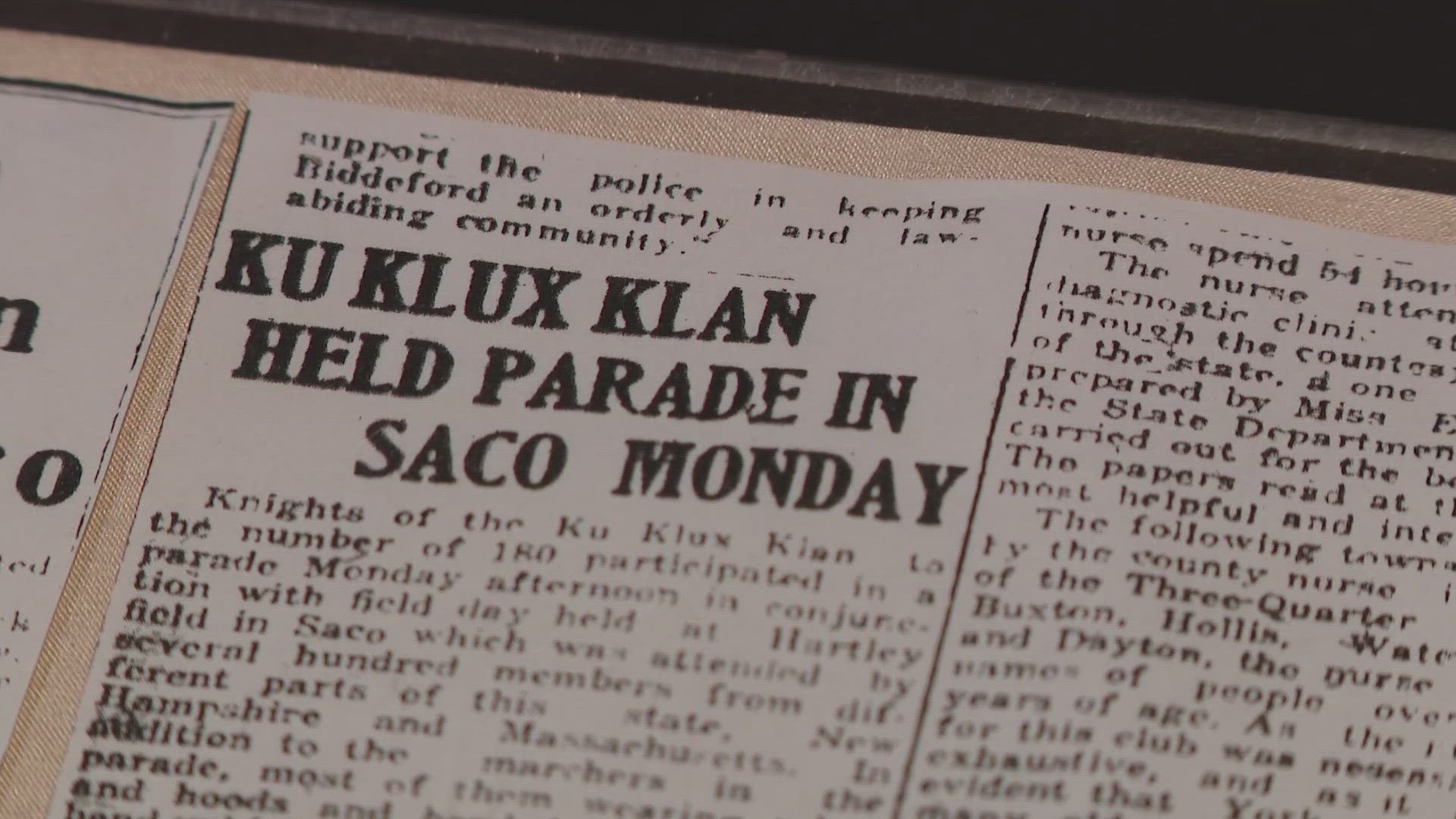

And into that divide came the Ku Klux Klan in 1924.

“I think most people in Maine have no idea of that history,” Biddeford native and former Mayor Alan Casavant said. “When they think of the Klan, they think of down South, but the Klan was here with different objectives and different targets.”

Indeed, the Klan was remarkably active in Maine in the mid-1920s, targeting immigrants and Catholics. The dominant immigrant populations were Franco-Americans from Canada and Irish, and both were predominantly Catholic. The immigrants came to work in the huge textile mills, and most lived in tenements in Biddeford.

Casavant said that was a big part of the division between the cities. The immigrant and Catholic workers lived in Biddeford. The mill owners and managers, whom he said were largely Protestant, lived in Saco.

At the Saco Museum, director Anatole Brown said the Klan helped to fuel the friction from economics, as well as cultural and religious differences, and that it gained a significant following around Maine, especially in mill towns.

“Gov. [Ralph Owen] Brewster of Maine apparently had Klan connections and had mayors around Maine, like Rockland, Portland and Saco, where they had Klan ties. “

Saco Mayor John Smith supported the Klan, Brown said. And when the Klan said it wanted to stage a rally in the city on Labor Day of 1924, Smith approved.

“John G. Smith ran as a Klan affiliate and ran on a ticket that he was 100 percent American," Brown said. "He promised there would never be any Catholic schools built in Saco.”

The reports were that the KKK planned to rally in Saco and then march across the river to Biddeford to directly show their grievances to the immigrant community. That, said Brown, raised the ire of Biddeford residents and that city’s mayor, Edward Drapeau, who vowed to not let the Klan into Biddeford.

“[He] said, 'You’re not coming here.' And he put reinforcements, police and fire, on both sides of the river,” Casavant, a retired high school history teacher, explained.

Casavant also recounted how Irish and Franco groups in Biddeford, who were typically fierce rivals, joined forces to also guard the bridges into the city against the Klan.

On the day of the rally, however, there was no actual confrontation. About 300 white-robed Klansmen showed up to rally in Saco, but the march never went to Biddeford.

Casavant said there was also a significant amount of opposition to the Klan in Saco, where he said “people jeered” at them.

The Klan came back the following year, said Brown, who has a 3- to 4-foot-long panoramic photo of around 200 Klansmen with faces visible, posing in front of a Saco school in 1925.

The Klan had a long tradition, Brown explained, of being a secret society, where members wore the infamous pointed hoods to conceal their identities and heighten the fear and intimidation. Their faces were clearly visible in that 1925 photo, he said, suggesting that local Klan supporters weren’t concerned about hiding their affiliation. Brown said he suspected some of the Mainers may also have been naive to the nature and practices of the Klan in other parts of the country.

That 1925 rally was the last one in the two cities, and Brown said Klan activity in Maine declined steadily in the next few years.

Many local people, Brown and Casavant both pointed out, may know little about the history of the Klan in their communities.

Jason Cote wants to make sure it doesn’t get forgotten.

The Biddeford native said he heard a bit about the Klan from his grandparents but began researching more when he became a history teacher at Thornton Academy in Saco.

Cote said he teaches that Klan history to his students, who are typically “shocked” to learn the hate group, so reviled in modern America, was once active in their town.

“Something extraordinary happened 100 years ago,” Cote said. "On one hand, there was this incredible manifestation of anxiety and fear that was monumental for the community. But at the same time there was resistance to that in both towns. And it saw a lot of people be brave and speak out in terms of acceptance and integration.”

That feeling prompted the teacher to urge local leaders to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the first Klan march. That ceremony—not a celebration, he points out—will take place at 3 p.m. Sept. 17, on the Main Street bridge in Biddeford.

Cote will be emcee for the event. Anatole Brown will speak, as will Alan Casavant, who said the anniversary provides a “teaching moment” to understand the continuing struggles of modern immigrants to gain acceptance.

“This event occurred a century ago, and the rhetoric being used—by members of the Klan, by nativists, by white supremacists—are the same words being used 100 years later, even though the targets might be different," he explained. "I see this as a historic moment but more important as a teaching moment to remind people of their own ethnicity and what their ancestors went through when they came to this country.”