ORONO, Maine — Ticks carrying diseases are moving farther north and west every year, reaching into new areas of Maine.

Scientists want to learn how the weather and wildlife on the move impact deer tick populations and the health risks to people. Deer ticks carry several pathogens that cause diseases, including Lyme.

Researchers at the University of Maine have launched an ambitious project tracking tick migration in real time. Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, secured funding for the project in July of 2023.

On a recent hot sunny day, UMaine students wore protective clothing, laced up their boots, and loaded their gear. They headed deep into the woods to learn more about tick activity.

John Nugent is the field coordinator for the pilot project launched by the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Tick Lab.

Researchers are setting up a weather station in this remote area to monitor conditions in the soil and air in real time.

"We are also monitoring wind direction, wind speed, light sensor relative humidity, and temperature," Nugent explained.

Hunting cameras on trees capture wildlife so scientists can see what host ticks are feeding on.

"Any large mammal hosts that might walk through this area," Nugent said.

The data are transmitted over cell networks and tracked in real time as researchers hope to learn the best conditions for ticks to thrive.

"That will tell us if they prefer this kind of climate or if it is suitable for them, and we can find climates farther north of here that are similar, here in Maine, that we can monitor in the future," Nugent said.

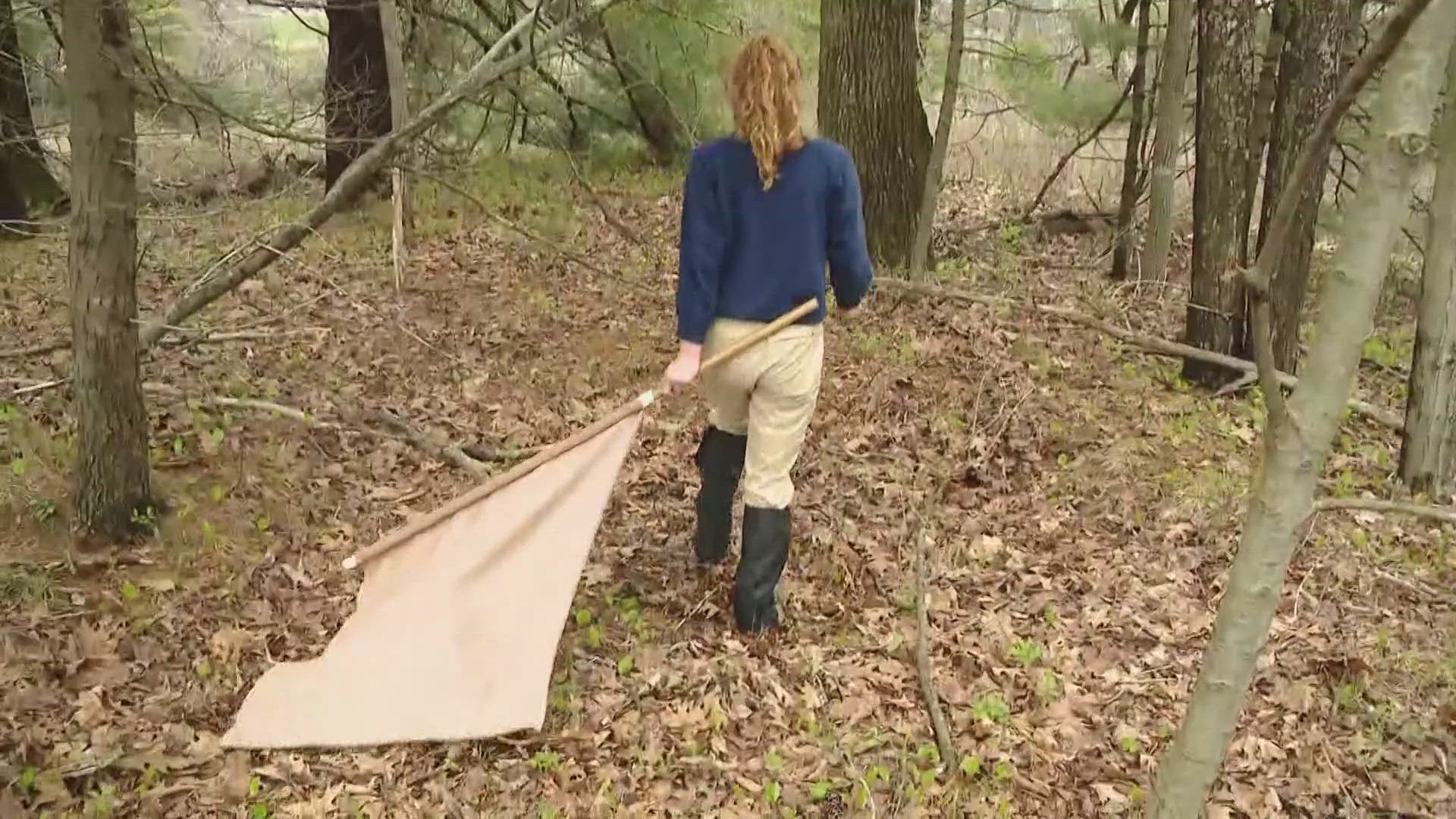

Will Kolbenson, a junior botany major at the university, dragged for ticks near the site.

Every 10 meters, Will checked his dragging cloth for ticks. The ticks are collected and tested for pathogens that cause Lyme and other tickborne diseases.

"My last lab job was working with plants, so it wasn't about public safety or human safety, so this feels more meaningful," Kolbenson said.

Data from 15 monitoring sites, from Wells to northern Maine and east to Mount Desert Island, could help scientists better understand why ticks are migrating into new areas of the state.

Griffin Dill manages the UMaine Tick Lab and said this project will allow them to see what is influencing their movement and the population change.

Experts say ticks need 80 percent humidity to thrive and don't do well in dry, sunny conditions or prolonged bitter cold when there is little or no snow cover. Dill said the stations measuring "micro-climates" could lead to answers.

"We don't know exactly what role climate change is playing. We expect it is going to mean more ticks and more pathogens. How is that going to shape their populations?" Dill mused.

Researchers in southern Maine are looking for tick species that have shown up in other parts of New England, such as the Lone Star Tick, which can cause allergic reactions to red meat, known as alpha-gal syndrome.

Data will be collected through the fall months when ticks are the most active. Conditions will also be monitored during the winter. The information will be released to the public about possible hotspots for ticks and the diseases they carry.