PORTLAND, Maine — For months after she was diagnosed with Stage 3 breast cancer, Rita Achiro didn't believe it was true.

She was 29. She knew of no other women who had battled the illness -- certainly no one in the tight-knit South Sudanese community in Portland, Maine.

But 18 months later, a double-mastectomy followed by radiation and a year of chemotherapy have taught Achiro just how savagely breast cancer attacks women, and Black women in particular.

"They just looked at me like, ‘Whoa.’ Like, 'How did you not know?’'" Achiro said of the doctors who told her the tumor was so advanced. "How would I know? I’m 29, for one … We don’t even have this in our community and if we do, no one has shared their story with me.”

And there’s the rub. Achiro’s tight-knit community is also tight-lipped. Simply put, they don’t talk about breast cancer or any serious illness.

As she re-emerges from the isolation of her treatment, and from COVID-19, Achiro is determined to end the stigma about cancer that haunts many immigrant communities. She is focused on spreading awareness among friends, other young women, and eventually, her young daughter.

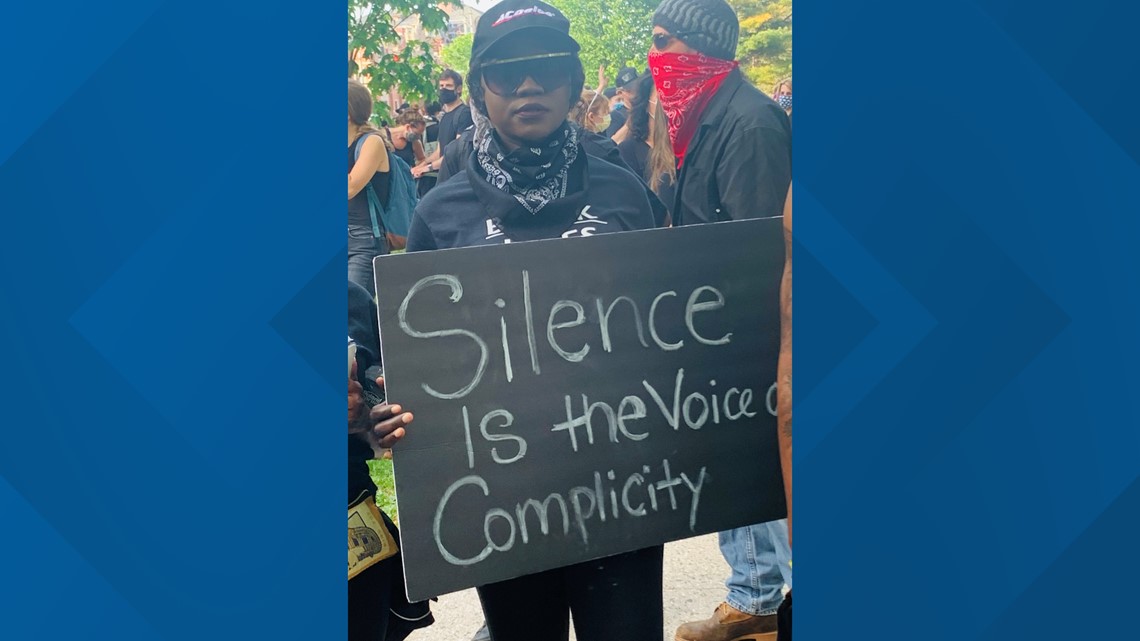

Achiro spent the summer of 2020 marching through the streets of Portland protesting the May 25, 2020, murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer.

Only her sister knew she'd spent the previous day watching toxic but life-saving chemicals flow into her body.

Achiro had kept her diagnosis -- a particularly aggressive form of Stage 3A breast cancer that had spread to the lymph nodes-- and her subsequent treatment largely to herself.

She didn't want pity. Even worse, she feared the stigma associated with serious illness in the South Sudanese community.

Achiro was 6 or 7 when she and her family fled the civil war in Sudan for refugee camps in Kenya.

"I was left in the middle of a civil war and survived that although I was almost killed when my auntie left me behind," she wrote in a text message. "Luckily a neighbor saw me sitting in the middle surrounded by dead bodies.”

In the years since, she graduated from Portland High School, became a Certified Nurses Aide, and is raising her daughter.

Decades after coming to the United States, however, fear and lack of understanding of cancer and other serious illnesses haunt some immigrant communities, particularly those from countries where chemotherapy and other advanced treatments simply aren't an option.

"Nobody talks about this in my community," Achiro said. “Nobody talks about any disease that is hurting them, that is killing them. It’s a stigma. It's a taboo."

So during the spring and into the summer following her diagnosis, Achiro told only her sister and two friends of her battle. Initially without health insurance, she continued to work despite regular chemotherapy treatments that left her exhausted.

Last summer, Achiro joined Black Lives Matter protests in Portland. One day in June, she stood for nine hours in Payson Park, waving signs and leading chants through a megaphone.

"The Black Lives Matter protests came and I said, 'I need to be a part of this, you know? I have to be there. I have to support Black lives,'" Achiro said. "With me having chemo and me feeling so weak … I went. I went from being in the back to being in the middle to chanting 'Black Lives Matter' to being in the front to speaking. I was so motivated to be a part of this movement because I felt like to be a part of this gave me the strength to push on."

On March 8 -- International Women's Day -- Achiro decided to end her silence. She acknowledged her diagnosis in a public Facebook post and said she would no longer battle cancer alone.

"We must speak about what we are going through and the disease that’s killing us, in order for us to heal and believe that in this journey of change, we are not alone," she wrote. "We must stop shaming others for having something that they did not ask to have. Instead of talking about them, gossiping or bashing them, I pray this new generation will be the support that many of our parents did not have... Why is it that we only talk about the living when they are no longer here because they died of such disease? No one should be crying for help silently when [there] is a huge African community."

Achiro's childhood friend, Nyamuon "Moon" Nguany Machar, said she is inspired by Achiro's bravery in confronting her diagnosis in public.

"To take that fear and that raw emotion and have it on display and at the mercy of a community that is so, sometimes, toxic towards that kind of strength and initiative was one of the bravest things that I’ve probably ever [seen]," she said. "That stigmatized conversation about many of the immigrant communities and African communities that have come here, that conversation of sickness and disease and ailments, is something that is always kept secret. So for her to step up and want to be the example of that and be the person that’s going to take this piece forward, that right there is like the silver lining."

But Achiro said the stigma she feared did surface when two elder family members phoned and asked her to remove her Facebook post.

One, she said, asked if her cancer had returned or had worsened.

"He's like, 'Well, why are you posting it,'" Achiro said. "I’m like, ‘Because I’m ready to talk about it.’ He’s like, ‘Why?’ And I’m like, ‘This is my story. I'm dealing with it, not you.’ He said, 'Oh, well people are calling me.' I’m like, "Well if you don’t want to talk about it, you can send them my way.’ I refused to take that post down ... I want someone who's silently fighting this to see my post."

Edward Laboke of Portland came to the United States from the same area of South Sudan. In the Acholi region, the word for cancer means any untreatable wound or sickness, Laboke said. Unlike in the United States, in much of South Sudan, diagnosis and treatment are not options.

"We have a lot of stigma about anything that is not treatable," he said. "People think a lot about it. Sometimes they think because you or your family has done something wrong to somebody and as the result of a curse from God you've got this."

Dr. Scot Remick is head of oncology at Maine Medical Center. He worked for more than 20 years in Uganda, Kenya, and other countries in Africa treating patients with HIV/AIDS and cancer. He said stigma surrounds terminal and life-threatening illnesses in many cultures.

“There is a lot of misinformation,” Remick said. “Many people have alternative beliefs, either religious or spiritual beliefs, [that] they’ve done something wrong that’s why they have this, so they can’t share it. You can see women come in with extensive tumors on their chest wall and they’re sitting with that for a long, long time before they come for medical attention because it’s taboo.”

Immigrants to the U.S. are often less likely to undergo cancer screenings and have worse outcomes than non-Hispanic whites, due in part to cultural myths and religious beliefs. Women from Somalia and Sudan are particularly vulnerable, according to a June 2020 report prepared for the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Achiro is determined that to combat that stigma by educating other Black women about breast cancer, encouraging them to talk about it, and urging them to get checked.

In March of this year, Nguany Machar organized an online fundraiser to help pay Achiro's medical bills. To date, it has raised more than $12,500.

"I never saw her not smiling as she would push past the pain and work tirelessly to give back to the community she love[s]," Nguany wrote. "As a community leader and as an activist, the call for change was still a call she answered. Throughout the summer you would find Rita marching and protesting alongside community members and allies mustering up what little energy she had to look past herself and amplify the voice of others."

Last month, Achiro's oncologist told her that after a few additional chemotherapy treatments, she should be in remission by June.

A friend plans to hold a "Walk for Rita” then, which Achiro said will be "a final walk to the finish line. Everyone is welcome because we are in this together. It reminds me of my fight this summer for my life, and for Black lives."

"It's been a tough journey, but I want my story to inspire the ones who never got their breast checked to go do it," she said. "It’s killing us, people of color. I’m not going to be part of that statistic."

Click here to help with Rita's medical expenses.