WARREN, Maine — The one experience guaranteed in life for every person on this planet is death.

Philosophers have grappled with the concept for centuries. Religious leaders have built mass followings around the idea of the afterlife. Different cultures have presented different interpretations of what death means. However, a commonality shared among many is that most people don't want to die alone.

In a lot of ways, hospice care is designed to address this fear.

These workers tend to a terminally-ill patient's needs—emotionally, physically, and spiritually—and are often with them when that patient takes their last breath. Hospice care workers will tell you it's a rewarding job. It's also challenging and can take a toll, especially for those who bond with their patients.

There are thousands of hospice care programs located throughout the country. One of them is at the Maine State Prison.

On a weekday morning in midwinter, Holly Reid stands in front of a small class of two men. They're in a room that looks like any other generic classroom. It has a whiteboard, covered in scribbled words from a lecture; long, wooden tables that serve as desks; plastic maroon chairs scattered throughout the space. Just outside a dew-covered window, though, is a tall fence with spiraling barbed wire at the top.

Reid has been coming to the Maine State Prison every week since 2019 as a volunteer chaplain. It is her duty to train a select-few inmates to take part in the prisoner hospice volunteer program, providing care for fellow prisoners who are either ill or dying in the prison's infirmary. This program began in 2001 in partnership with the Maine Hospice Council.

"I just really fell in love with the group and with the men and with the work that they were doing," Reid said.

Reid said she covers a variety of topics with these inmates, all related to hospice. They run the gamut from religion and spirituality to awareness about death to how to be an active listener and a good communicator.

Reid said she has seen how this work transforms the men these inmates are taking care of, leading with love and vulnerability, a concept somewhat unusual for a corrections environment. She said she feels this work has changed her, too.

"Before I started coming here, I had my own biases about who was incarcerated and why they were incarcerated and what type of person that must be," Reid said.

In order to take part in this program, these men must have served at least five consecutive years behind bars without any writeups. The rigorous course they eventually graduate from is 100 hours total, and the first 40 involve medical training with a full review of the body's systems.

"It was definitely overdue. Corrections, as a whole, needed some sort of program to address the fact that some of our patients are going to be here for the rest of their natural life," Brian Castonguay, the health services administrator for the Maine State Prison, said about the hospice program.

Castonguay said it can be a jarring or upsetting experience for a person to witness someone die, if they never have before. That's why in training, inmates learn about normal signs of aging, what to expect as a person gets older, and what happens when someone is actively dying.

He said he believes this program has slowly helped his medical staff and the prison hospice volunteers build meaningful relationships.

"It’s not just ‘them’ and ‘us,'" Castonguay said. "We are truly, at the end of the day, here for the same reason."

Castonguay said his hope is that participation in the hospice program will have an impact on these prisoners, even in the free world.

"My hope would be that when someone were to leave that they would be on a trajectory that would keep with the same spirit that awakened in them when they were here; and avoid recidivism by not committing the same crimes, maybe not being connected with the same people," Castonguay said.

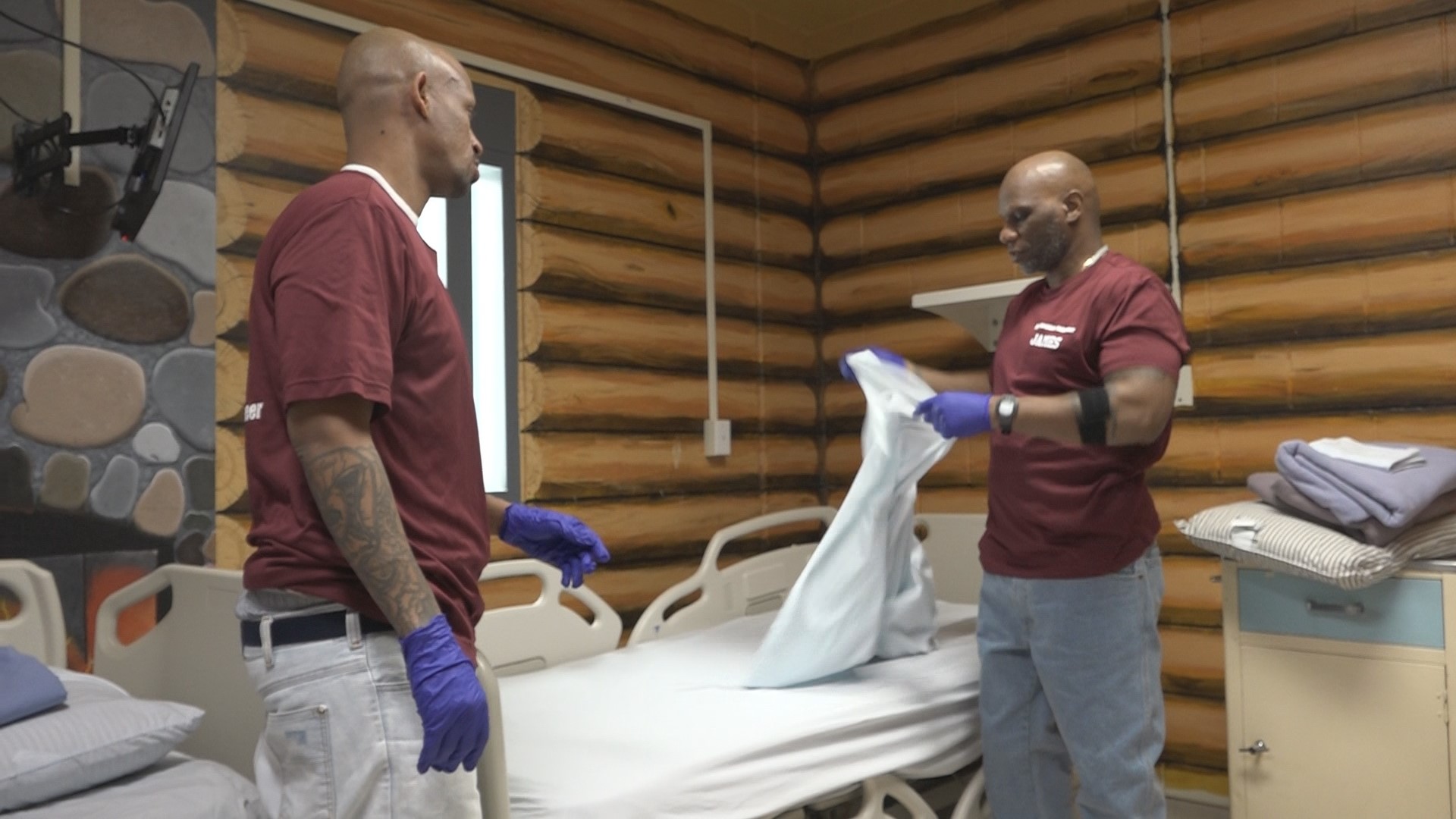

James Love and Abdi "Lalee" Awad have been fully trained hospice volunteers since last summer. Love has been incarcerated at the Maine State Prison since 2003, when he was transferred from Maryland, where he worked in the infirmary there. Awad has been incarcerated since 2011 and was recently found guilty in another cold case, extending his sentence. Both men were charged with and found guilty of murder, in some capacity.

"When I first came to prison, I was 18 years old. And I came to prison with a life-plus-20-years sentence," Love said.

Love said he is not the same person now he was back then.

"Twenty-five years ago, I wouldn’t have expected myself to be doing this type of work, but I’m glad I found the path—the righteous path," Love said.

"This is the most wonderful program I have ever been a part of. … It’s a life-changing experience. It changed my life a lot and my ways of thinking and just being there for fellow man, my fellow residents," he added later.

Love said his family outside of prison is proud of his success, including his aunt who is actually a hospice worker, too. Through this program, Love said he has learned the importance of offering comfort when someone is dying.

"A lot of guys in here ... don’t have family members, very few friends," Love said. "Even in prison, you don’t want to die alone."

Recently, Love and Awad cared for an especially important person in his last days: one of the founding resident members of the hospice program, who was involved in training them.

"I knew he heard every word that we said to him because of those little sighs. We said corny jokes, and even though he was sedated—we talk[ed] to him, rub[bed] his hair, stroke[d] his hand," Love said.

"It’s almost like a part of you leaves with them," Awad said.

Awad said for him, this program has provided a sense of camaraderie with fellow volunteers. None of them are getting paid to do this work, but they follow an on-call schedule and generally work in pairs, learning what one another's strengths and weaknesses are. He said when a resident is dying, there is always someone in the room with them.

"Having this shirt grants you like a brotherhood a bit," Awad said.

He said he has learned one of the most important life lessons here: selflessness.

"It’s not about you. It’s about the patient. Everything you do has nothing to do with you. It’s for the patient," Awad said. "You don’t approach it as the person who is saving the day. You don’t come in to do that. You just show up as you are, and however [the patient] receive[s] you, that’s how you perform."

For Awad, this program has given him a different perspective about death.

For nearly a year, these volunteers have been taking care of Ronald Piskorski, a 75-year-old man with a life sentence who has been in prison since the 1970s and in the Maine State Prison specifically since 1997. He came to the infirmary last April after he said he got a case of walking pneumonia.

"I appreciate [the help] 100 percent. When they get ready to go, I thank them a dozen times every time they come because it means so much to me. They help me a lot," Piskorski said.

Piskorski said he has known Awad for more than a decade and Love for more than two decades. He said he hopes they're there for him in his final days, which he knows will likely be behind bars.

“I see what they have done for other people that were in worse shape than myself, and I say to myself, ‘I hope I have them,'" Piskorski said.

Maine State Prison correctional chaplain Diane Carlson said in many ways, this program is about fundamental change, noting she believes it's possible. She said 20 years ago, she was an active addict and had to find her way out of that.

"I may not have ended up in a prison setting, but I definitely was damaged and needed healing myself, and I think the more support we can give people, the better chance they have to heal," Carlson said.

She said there are now 17 or 18 recognized religions with the Maine Department of Corrections and 12 active ones at the Maine State Prison. She said she works to make sure the customs of different religions are recognized and honored at the time of a resident's death. That show of respect extends to the volunteers, as well.

"When somebody is to the point where they’re thinking about taking the hospice class so they can volunteer, they’re at a pivotal moment in their life," Carlson said, later adding, "I think people that do this program, volunteer for this program have more insight into how tender people are and how valuable life is.”

Carlson said so far, 38 Maine State Prison residents have died while in hospice volunteer care. Forty-seven residents have graduated from the program.