Karen Evans has been in and out of the mental health system since she was 17. Today she is 73. She can recall symptoms of her psychosis – hearing voices – back to when she was just a child.

At one point, those voices convinced her to light herself on fire, and she suffered severe burns over much of her body. As part of Maine’s behavioral health care system, Evans has been on and off anti-psychotic medications for decades and was at one point a patient at—and part of the state’s consent decree with—the former Augusta Mental Health Institute (AMHI).

Evans, of Portland, also recently served on the Legislature's Mental Health Task Force. She and others are sounding the alarm on a mental health crisis silently exploding

"Mental health has not been a priority in Maine, except for the substance abuse arm of it," she said. "But mental health itself does not get very much attention anymore and I think the mental health system is in trouble. I think it's in big trouble."

Providers and clients say Maine’s mental health system was “threadbare” prior to the pandemic, and is now collapsing under the strain of COVID-19.

Organizations that contract with the state to provide behavioral healthcare, education, and residential services to Maine children and adults say they've received none of the $1.25 billion in COVID-19 funding allocated to the state through the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act, the $2 trillion stimulus bill passed by Congress in March.

So many families are on a waiting list to receive mental health services for their children that case managers have simply stopped referring people to the service, “because there is no point,” Eric Meyer, President and CEO of Spurwink, told NEWS CENTER Maine earlier this year.

Although the providers, from Sweetser and Spurwink, which offers inpatient, outpatient and residential behavioral health services to 8,500 Mainers intellectual disabilities and autism each year, to smaller, regional providers such as Tri County Mental Health Services, have received other funding, including some from the federal government, the lack of CARES Act funding has left many frustrated and baffled—and already cutting services.

That frustration grew after learning that Maine failed to receive a $2 million federal grant specifically designated for behavioral health services due to what the state described as "a technical glitch," but the federal government said were actually errors in the application.

Maine was not eligible for a second $2 million grant because the state has no federally-qualified community health centers.

Without funding, some providers are already eliminating services for people with severe mental illness, while others continue to struggle to remain open at all.

In May, providers of behavioral health care in Maine warned that even as Maine coped with COVID-19, a second pandemic was looming as those struggling with mental illness and substance abuse buckled under additional stress and lack of access to services, whether due to logistics or funding.

"People are so confused and scared and anxious and depressed," Joe Everett, President and CEO of The Opportunity Alliance, said at the time. "And increased suicidal ideation -- not that they have the intent, but they're so overwhelmed because they already have a complicated life ... the people we support live with such struggles anyway ... the playing field is so unfair."

With the Legislature out of session until only recently, Gov. Janet Mills was charged with allocating the $1.25 billion Maine received under the CARES Act.

As of July 23, $584 million of that had been set aside to purchase personal protective equipment, enhanced testing and to support public health in towns and schools, Mills' press secretary Lindsay Crete said.

Approximately $666,000 of that funding remains, although requests for funding far exceed that, and, "This remaining amount is vastly inadequate to the state’s needs,” Crete wrote.

But organizations that contract with the Maine Department of Health and Human Services to provide state-mandated behavioral healthcare services say the funding they've received is vastly inadequate to treat the adults and children with severe mental illness and intellectual disabilities in their care.

They say the state's mental health system was "threadbare" before the pandemic hit, and is now collapsing as funding is directed elsewhere.

In mid-February, just prior to the pandemic hitting Maine, Sara Squires of Disability Rights Maine testified before the Appropriations and Health and Human Services committees that more than 1,000 children remained on a waiting list for services for mental health and developmental issues, and “untold numbers of children are receiving less than adequate services,” despite increased resources by the Mills administration.

Many agencies have lost millions of dollars, with some predicting revenue loss of up to 40 percent, Meyer, of Spurwink, told the Appropriations Committee in June.

Catholic Charities of Maine also closed their ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) Team (high-level care for people with severe mental illness) within the past few months due to lack of funding.

Sweetser, a community-based mental health, education, and residential treatment provider for children and adults and the largest provider of crisis services in the state, notified the Maine Department of Health and Human Services in April that due to increased costs resulting from the pandemic, it could no longer fund medication management services for 596 clients.

“There are additional costs associated [with] the pandemic that have not been adequately covered particularly for not-for-profit organizations with more than 500 employees,” Susan Pieter, spokeswoman for Sweetser, said in an email to NEWS CENTER Maine.

While many services have been transitioned to telehealth—a change that carries its own costs—many others (particularly those for children and people with intellectual disabilities) cannot be.

Expensive personal protective equipment is used at an exponentially higher rate when staff interacts with adults and children with intellectual disabilities, providers say, and the costs of hazard pay or even double-time to retain staff to work during a COVID-19 outbreak in a residential facility is overwhelming.

Medication management is expensive for agencies to provide, but also critical to a client's success.

"There are frequent med changes, people on multiple antipsychotic medications need frequent visits, and we know that if we aren't providing that service, there aren't that many other places to refer them to," said Julie Olum of Tri County Mental Health Services. "A primary care physician is not going to be comfortable prescribing those types of medications. For those clients, there's not really another alternative. They can go sit on a waiting list for nine months."

Lydia Richard of Milo in Piscataquis County receives disability for depression and PTSD. She receives medication management, case management, counseling, and peer support services through MaineCare.

Prior to COVID, she'd travel 45 minutes each way to get those services in Bangor. Richard told NEWS CENTER Maine that when her medication manager ended his practice, she was told to find her own replacement, and was then told that because she'd taken the same medications for so long, her primary care physician should manage them.

"So when I was having a hard time when all this coronavirus started, my doctor said, "Are you still seeing your medication management person?'" Richard said. "I said, 'Remember, that's you now.' She said she'd forgotten.'"

Richard said she hasn't had any contact with her doctor in months, no medications have been adjusted, and her refills are phoned in.

"It's so difficult to navigate everything,” Richard said. “It’s kind of like you just want to give up because it’s just so difficult to try to get what you need.”

Tri County Mental Health Services, which serves about 3,000 clients each year in Androscoggin, Franklin and Oxford Counties, as well as several additional areas, was in "dire straits" for about a month immediately after the pandemic hit, Julie Olum said. They shut down their social learning center and lost a major source of revenue, resulting in immediate layoffs.

“We were banging on every door at the state level trying to get some help, some relief, some grant dollars, but we didn’t get very much. Finally, we got $200,000 to $300,000 in grants. And we were one of the lucky ones with the Paycheck Protection Program. That saved our lives.”

Maine’s failure to secure two separate $2 million behavioral health grants received by most other states only made the lack of funding worse.

According to Farwell, Maine failed to receive a $2 million grant from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) made available to all states due to a “technical glitch.” Farwell said in an email that Maine applied by the deadline but “later learned of a technical glitch with the application validation process on a day when the state government was closed due to a storm and power was out in much of the state.”

“SAMHSA refused to extend any flexibility to Maine,” she wrote in an email, adding that Maine also objected that the grants had been presented as noncompetitive even though the federal government did not have sufficient funding to award all the grants announced.

But in an email to NEWS CENTER Maine, a spokesperson from SAMHSA, the federal agency that awarded the grants, provided different information about why Maine did not receive the funding:

“This was a competitive grant opportunity, and applications all had to be in by a certain timeline. The funding announcement stated that the application had to have been error-free by the due date and time specified. Maine submitted an application, but it was returned for errors and not submitted in time for the announcement.”

Farwell did not respond to an email seeking clarification.

Nor did Maine receive a $2 million grant allocated to states that have federally-certified community behavioral health centers.

Of the centers, Farwell said DHHS “is actively exploring the model and has supported provider organizations that are working to receive certification to become a clinic through SAMHSA.”

Asked at a July press briefing why none of the CARES Act funding had been directed to behavioral health services, Maine DHHS Commissioner Jeanne Lambrew said the administration had talked since the beginning of the pandemic about the importance of maintaining access to healthcare including behavioral healthcare, and had provided support for telehealth and hotlines.

Lambrew added, “I will say that as we also look at what’s going on in our health system, we are trying to protect and preserve what we have. We’re quite worried about maintaining benefits and maintaining coverage in light of the economic impact of COVID-19 … we also … are carefully looking at ways we spend that CARES Act funding to make sure that we someday down the road don’t have to cut.”

Crete, on behalf of the governor, said the administration has dedicated “several streams of federal funding that are separate and distinct from the $1.25 billion in the CARES Act.” Farwell provided the following information about that funding:

- DHHS used nearly $1 million from SAMHSA "to help Maine people cope with the psychological effects of the pandemic" including crisis counseling for people diagnosed with COVID-19, a public awareness campaign and support for crisis hotlines.

- The state received an $8.6 million grant from SAMHSA for children’s behavioral health.

- An executive order issued by Mills facilitated, relaxed restrictions on syringe exchange programs, and allowed greater flexibility with Narcan and methadone.

- Mills created a $35 million Coronavirus Relief Fund to allow nonprofit organizations to apply for FEMA disaster assistance. Eligible nonprofits include healthcare and behavioral healthcare organizations -- as well as arts and other nonprofits.

Farwell said the Office of Behavioral Health has applied for nearly $21 million in grants since the beginning of the pandemic. She did not respond to questions about how much of that funding was received or which programs benefited.

Other sources of federal funding include temporary increases in the Medicaid reimbursement rates for some services and the Federal Provider Relief Fund which allows Medicaid providers to receive up to two percent of revenue lost during the pandemic.

Spurwink also received about $1 million in provisional federal funding, according to vice president Kristen Farnham.

But providers and lobbyists, including Malory Shaughnessy of the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, Maine, and the Maine Behavioral Health Foundation, say none of the $1.25 billion in CARES Act funding has been dedicated to the “behavioral health safety net.”

“And look at Medicaid expansion,” Shaughnessy said. “Forty to 50 percent of people enrolling are getting mental health and substance abuse treatment, and there’s no money [from the CARES Act] dedicated to that safety net directly."

So in July, Meyer, who also serves as president of the Alliance of Addiction and Mental Health Services, asked the Legislature’s Appropriations Committee to spend $35 million of the remaining CARES Act funding to establish two COVID Relief Funds specifically designated for community behavioral health.

The first fund, for $15 million, would be applied to lost revenue in Fiscal Year 2020, and the second, for $20 million, for Fiscal Year 2021 and the next six months.

Of the request, Lindsay Crete, from Mills’ office, said, “The administration is taking into consideration these important requests, but one thing is clear: the need for funding far outpaces what Maine has. The governor continues to urge Congress to provide additional, substantial aid for states and greater flexibility in the use of those funds so that it can be better poised to help support organizations like Maine’s behavioral health service providers during this tremendously difficult time.”

Meyer and Shaughnessy said Monday that the administration has taken no action on the request for funding.

Pierter said Monday that Sweetser or the clients themselves have found new providers of medication management for all but 150 of the 596 clients whose medication management Sweetser discontinued and that the organization will work with the remaining clients to find providers.

Spurwink is now providing services for many of the former ACT team clients.

But providers say other services remain in jeopardy, and vulnerable clients are at risk.

Meyer said in May that he understands the state "is on a fiscal cliff of their own” and that the financial situation "is going to be bad."

"But the reality is our services have been underfunded for a long, long time and we're struggling to keep our doors open,” he said. “We hopefully can absorb a provider or two closing, but if five or 10 fail, we'll have a new level of crisis that I'm not sure we're ready for."

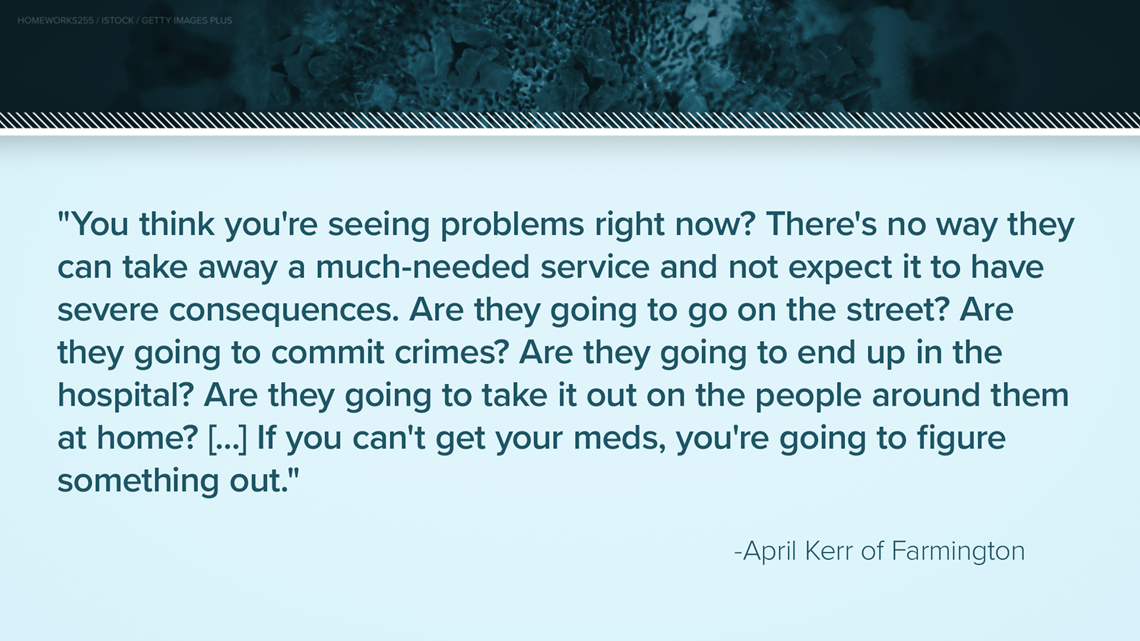

"You think you're seeing problems right now? There's no way they can take away a much-needed service and not expect it to have severe consequences," said April Kerr of Farmington, who receives services through the state for anxiety disorder and depression. "Are they going to go on the street? Are they going to commit crimes? Are they going to end up in the hospital? Are they going to take it out on the people around them at home? The violence, the depression, the suicide, and the self-medicating ... if you can't get your meds, you're going to figure something out."

Rep. Drew Gattine (D-Westbrook) is House Chairman of the Legislature's Appropriations Committee. He said Monday that with the Legislature not in session, all committee members can do is meet and listen -- which they have done over the past month.

Democrats on the committee wrote to Mills urging her to provide funding for schools, small businesses and, in particular, social service providers, he said.

"One of the things we commented on was we didn't really see any targeted relief for entities like mental health , substance abuse disorder, intellectual disabilities, eldercare," he said. "A lot of us think there needs to be a greater focus on community-based services. This pandemic is really a healthcare crisis and there are vulnerable people whoa re particularly at risk and it needs to be a priority."

But Rep. Charlotte Warren (D-Hallowell), Chairwoman of the Legislature's Mental Health Task Force, said the Mills' administration's two budgets included "no money for community-based services. I hope that it will change ... but places are closing, providers are having to lay people off. We've heard this story over and over and it hasn't been remedied."

Members of Maine's Congressional delegation did not respond to individual requests for comment but instead issued a joint statement saying, in part, "We are pushing hard for additional funding in the next relief package so that these resources will be available for Mainers who need them."

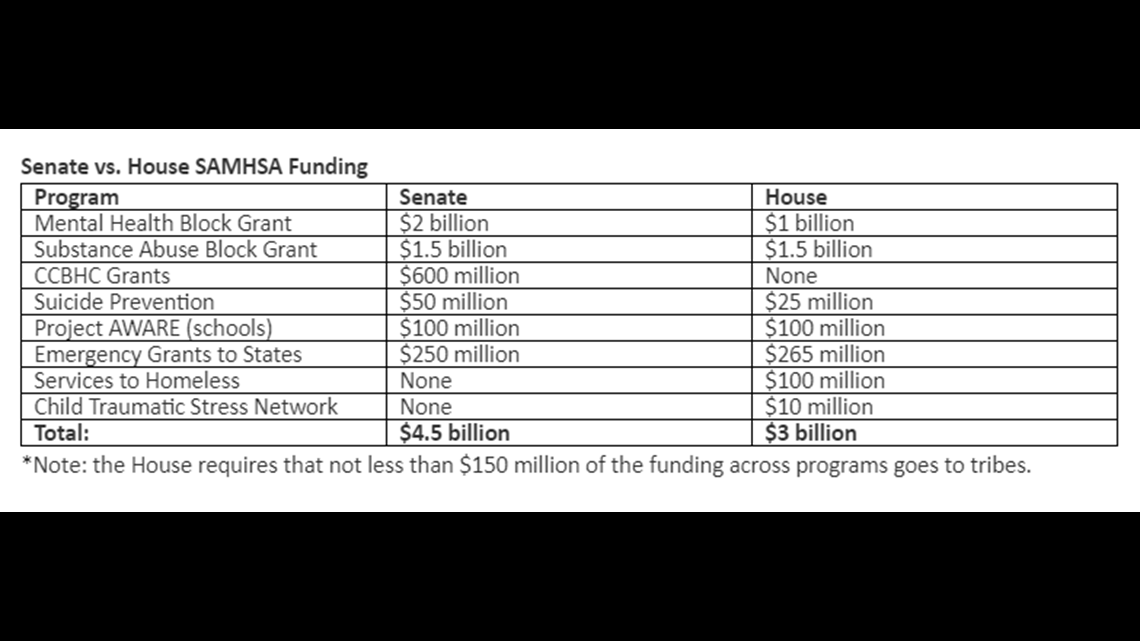

Congress continues to debate versions of the next federal relief package. The current Senate version includes $4.5 billion in funding for SAMHSA, while the current House version includes $3 billion.

"We don’t know what the final product will be, if they have a final product,” Shaughnessy said Monday, noting that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has said she’ll call Congress back if necessary in order to pass a stimulus bill, but that the Senate is scheduled to begin its August recess on Monday.

Regardless of any new relief act, though, she holds out hope that the $35 million requested from the state as part of the CARES Act will be approved.

“At least some, to help folks stay whole,” she said. “Because God knows, this is not going away.”

--

At NEWS CENTER Maine, we’re focusing our news coverage on the facts and not the fear around the illness. To see our full coverage, visit our coronavirus section, here: /coronavirus