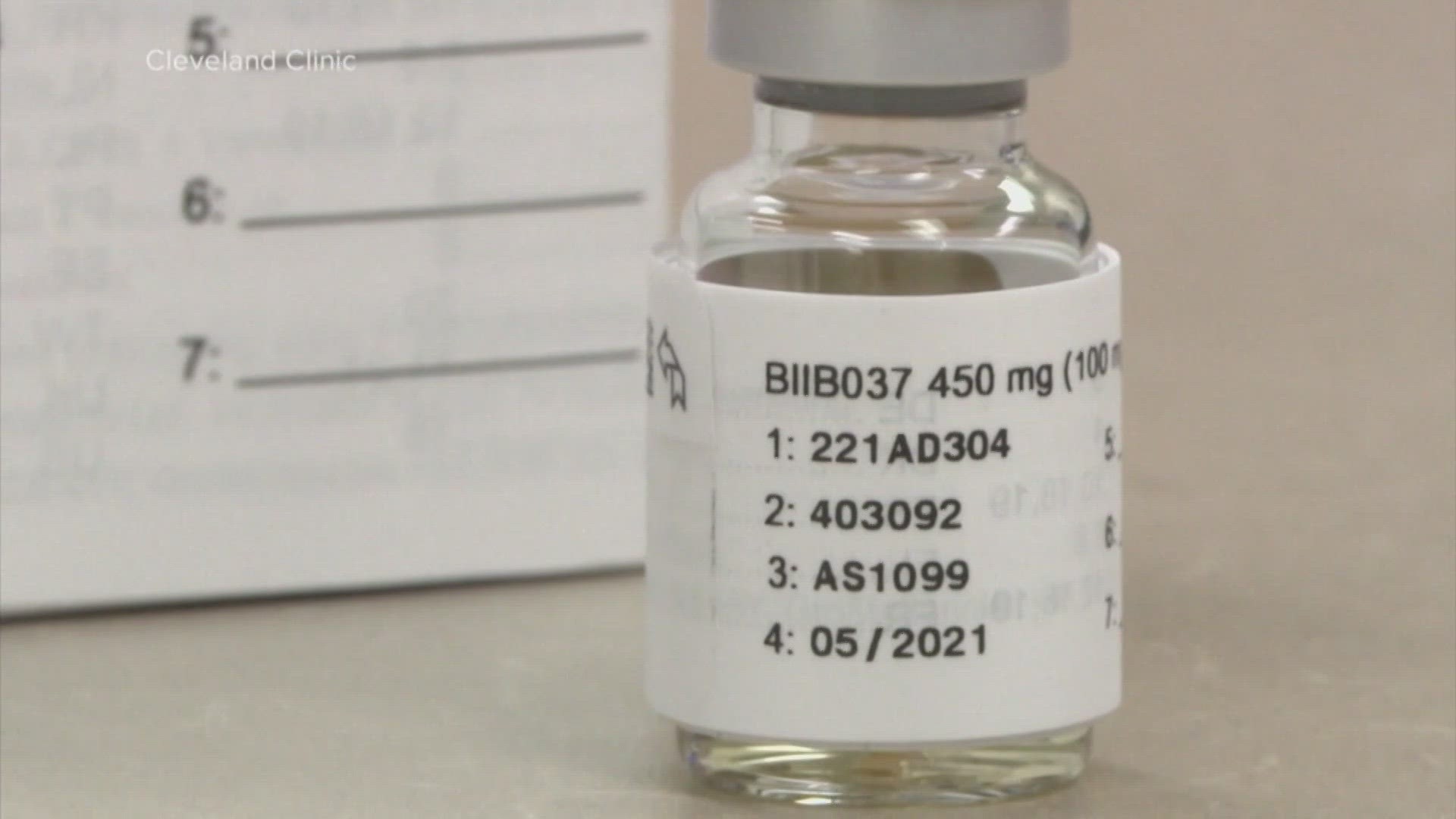

MAINE, Maine — A new treatment for Alzheimer's disease could bring new hope for patients and their families here in Maine. It's sold under the brand name Leqembi (Lecanemab-irmb), is made by Biogen, and it's been shown to slow the progression of the disease for patients in the early stages.

The new drug got accelerated FDA approval, and the FDA will make a decision on July 6 about weather to grant it full approval.

Don Moore lives in Orono and is a patient in the early stages of Alzheimer's. Moore has been working closely with Dr. Cliff Singer after his diagnosis.

Singer is the director for the Mood and Memory Clinic at Acadia Hospital in Bangor. He's the chief for the Center for Geriatric Cognitive and Mental Health and the director of the Robert C. Strauss Neurocognitive Research Program.

"This disease, my mother and father had it," Moore told Singer.

"In your family, clearly there are genes that increase the person's risk," Singer replied.

A few years back, when he was 76, Moore was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. He is 82 now, and the progression of the disease has been really slow.

"It does seem to be going slowly, but it is increasing," Moore told his doctor.

"How do you notice that?" Singer asked.

"Because I forget things. I mean, we are proactive to make sure I write something down or do something to help me remember," Moore responded.

Singer said Moore is a prime example of someone for whom the drug Leqembi could work.

"The Alzheimer's disease, in Don's case, is really limited to an area of the brain specializing in memory, where the rest of the brain is still health. So, if we can preserve those areas of his brain, that will be a wonderful thing," the doctor explained. "Drugs that reduce the burden of amoloid in the brain can be helpful. The lecanemeb trails prove that. But it's not a cure. The data suggests that it slows progression over 18 months by about 30%."

According to the Alzheimer's Association, 29,000 people 65 and older have Alzheimer's disease in Maine.

"We've got, as a society, difficult decisions to make [about] whether to pay for treatments that don't improve function but do slow the rate of decline. Clearly that's what families and -- as a healthcare provider -- I want. But it's expensive," Singer said.

Lequembi costs about $26,000 dollars a year, and Medicare won't cover it for now.

"It costs so much that you have to wonder for the next few years, is it worth it? I mean seriously. Is it worth that?" Moore said.

"If Medicare pays, we might think differently. When you want to protect your loved one and keep them going as long as they can, you are willing to do anything," Don's wife, Paula Moore, said.

Singer said that while he doesn't like the idea of Medicare not paying for the drug, he understands why.

"There is going to be compromises in other ways. People will have to pay more for their Medicare. That's going to be a hardship or they'll have to reduce reimbursement for other healthcare," Singer said.

Moore is focusing his time in doing things that keep his memory active, like reading the newspaper, playing chess, doing house chores, socializing with friends, family, and Paula, eating healthy, exercising, and anything else that could help slow the progression of the disease.

"So, if I really need to remember something, I have to write it down," Moore said.

Singer does say that even though the medicine is a total breakthrough, he hopes more promising drugs are developed in the future with more potential to impact more people who have the disease. For now, Singer said he is reluctant to prescribe the drug, but it is available.

The United States Veterans Health Administration recently said it would cover the treatment for veterans with early stages of the disease.