MAINE, USA — On a Monday in September 2022, a semi-retired Livermore Falls resident requested the removal of a graphic novel from the shelves of the local school library. It was the seventh official challenge the area’s school board received that month.

The challenger, Arin Quintel, had no children in the school district, though she said she previously volunteered as a foster grandparent in the local elementary school. She eventually left the volunteer program, concerned by the direction she felt the education system was headed — including an unnecessary focus on gender and sexuality, she said.

Hoping to make a difference in other ways, she had begun attending school board meetings and getting involved in local issues.

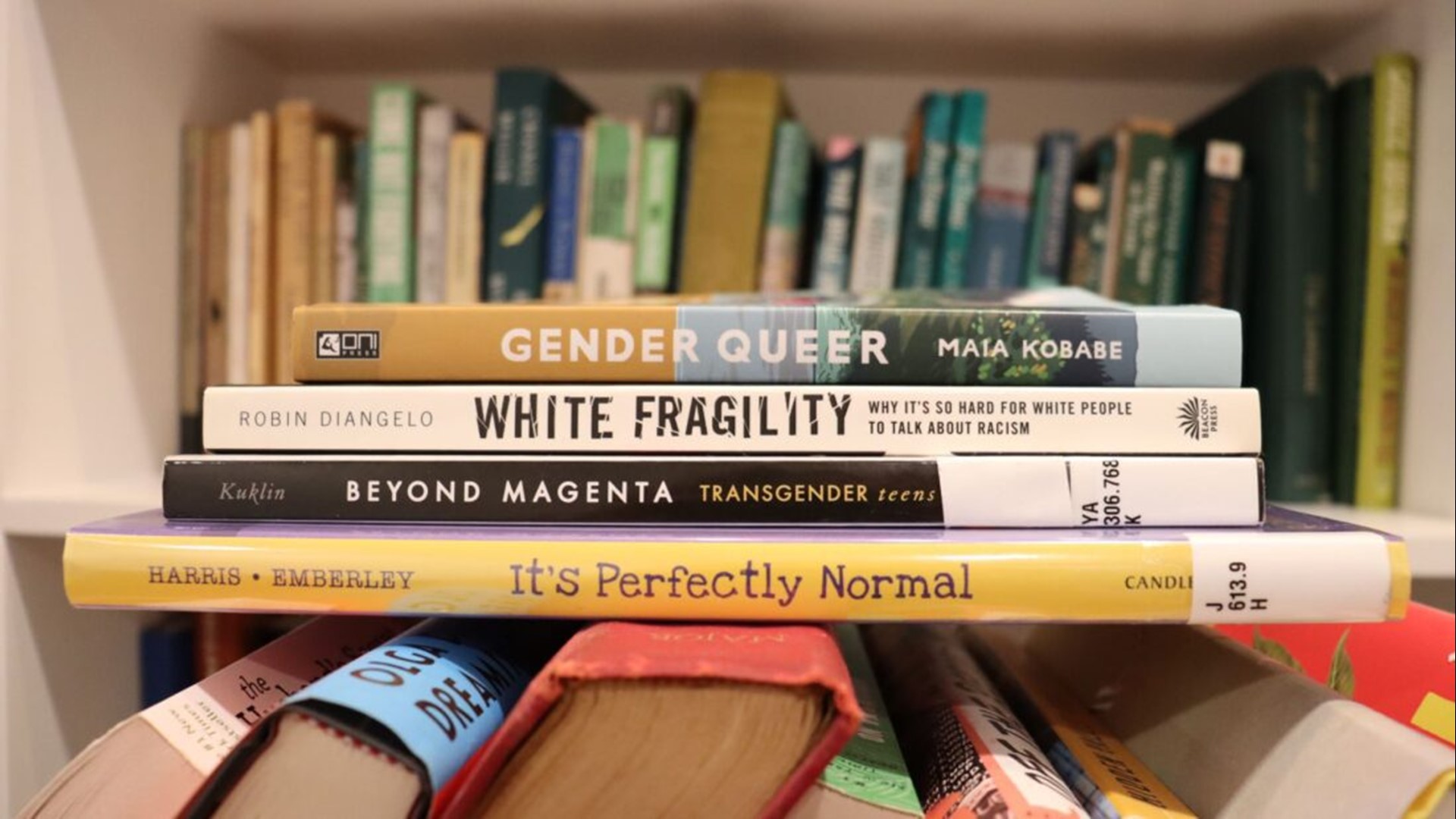

One day, while scrolling through her Twitter and Facebook accounts, Quintel came across Gender Queer: A Memoir, an illustrated autobiography about gender identity and being nonbinary, with illustrations of sex, which critics argue are inappropriate.

“It was all over the internet,” she said. “They were plastering it. People were posting pages out of it.”

Upset by what she described as the “pornographic” images in the book, she went to the school district to request its removal. She hadn’t read the book in its entirety, but the pages she saw online were enough. Eventually her challenge, with those of four other community members, went before the superintendent and school board.

In November 2022, the board voted to keep the book in the school library.

Quintel’s challenge was one of at least 22 that were filed and escalated to superintendents and school boards across nine districts in Maine in 2022 and 2023, a Maine Monitor analysis found.

In all but two challenges, critics complained about the sexually explicit nature of the books, which often dealt with LGBTQ themes.

Only one district has removed a book after a formal, written complaint, the first-of-its-kind Maine Monitor analysis found. That removal, targeting Gender Queer, was in response to three separate challenges in the district, RSU 56 in Dixfield.

In the vast majority of cases, school boards voted to keep the book, citing its merits. Experts and committee members noted that the explicit pages often had been presented out of context, without an understanding of the larger role the content played in the narrative. One challenge is ongoing.

In a few cases, the books were initially removed or relocated to a guidance counselor’s office. All of these decisions were overturned. In at least one instance, the book was retained but relocated to a section of the library for older students. Library configurations vary district to district and can sometimes serve students across a wide range of ages.

About one-third of the community members who filed challenges reported not having read or reviewed the book in its entirety, the Maine Monitor analysis found. The Monitor obtained copies of 19 of the 22 challenges, and reviewed the status of the other three.

In at least two cases, challengers explicitly noted that they relied — at least partially — on material from BookLooks.org, an organization started by a former member of the conservative national advocacy group Moms For Liberty. Although Moms for Liberty does not claim any chapters in Maine, nationally the group has been linked to book challenge efforts.

The BookLooks site reviews and rates books, with a focus on “objectionable material,” including content that may be “explicit, offensive, or obscene.” A number of complaints in Maine include screenshots of pages from the books, which align closely to those included on BookLooks.org reviews, although it is not clear if this is where community members learned of these images.

Gender Queer: A Memoir, the text Quintel wanted removed, was the most frequently challenged book in the state, the Monitor’s review found. Of the 22 complaints filed, 15 were aimed at Gender Queer. In 2022, it was also the most challenged book nationwide, according to The American Library Association’s State of America’s Libraries Report.

Book challenges in Maine school libraries have sharply increased over the past few years. In 2013, no books were officially challenged in school or public libraries, according to the American Library Association, including information shared by the Maine Library Association.

For the next nine years, no more than three books were challenged annually in school and public libraries.

That changed in 2021, when there were at least 11. There was a record number in 2022 — at least 17 challenges in school libraries.

In addition to the 22 challenges documented by the Monitor, there are instances where books were removed following a verbal complaint. Those are included in the American Library Association’s overall count, but not in the Monitor tally.

“We have never seen as many challenges as we are seeing right now,” said Heather Perkinson, the president of the Maine Association of School Libraries. “We can barely keep up with it.”

Despite the low success rate of book challenges in Maine, they come at a cost.

One superintendent estimated that for each challenge, the district spends between $1,000 and $3,000, depending on the length and complexity of the book. Another estimated that 35 hours of salaried staff time is required to review each book. School boards often buy copies so members can familiarize themselves.

Librarians and teachers on review committees also report facing harassment, online and in person.

“All of that is taking time away from supporting the students, parents and staff in our schools,” said Barbara Maling, principal of York Middle School.

Even so, district leaders emphasized the importance of following the process, despite the costs, in order to consider the challenges calmly and objectively.

“Following policy is important because we’re all human. And human emotions can take over in any situation,” said Clay Gleason, superintendent of the Bonny Eagle School District, which serves five towns, including Buxton. “If you’re following policy and trying to stay out of the weeds of the emotionality of the issue, it serves us all well.”

Maine school districts appear to be following procedures and policies well, said Tasslyn Magnusson, an independent researcher who tracks censorship broadly in partnership with EveryLibrary. She is also a consultant for PEN America’s Freedom to Read Program. The process of vetting the challenge typically leads to an understanding that “the book is in the library or in the classroom for a particular reason.”

Magnusson said she advises district leaders to “use your policies. Use your procedures. That’s the path through.”

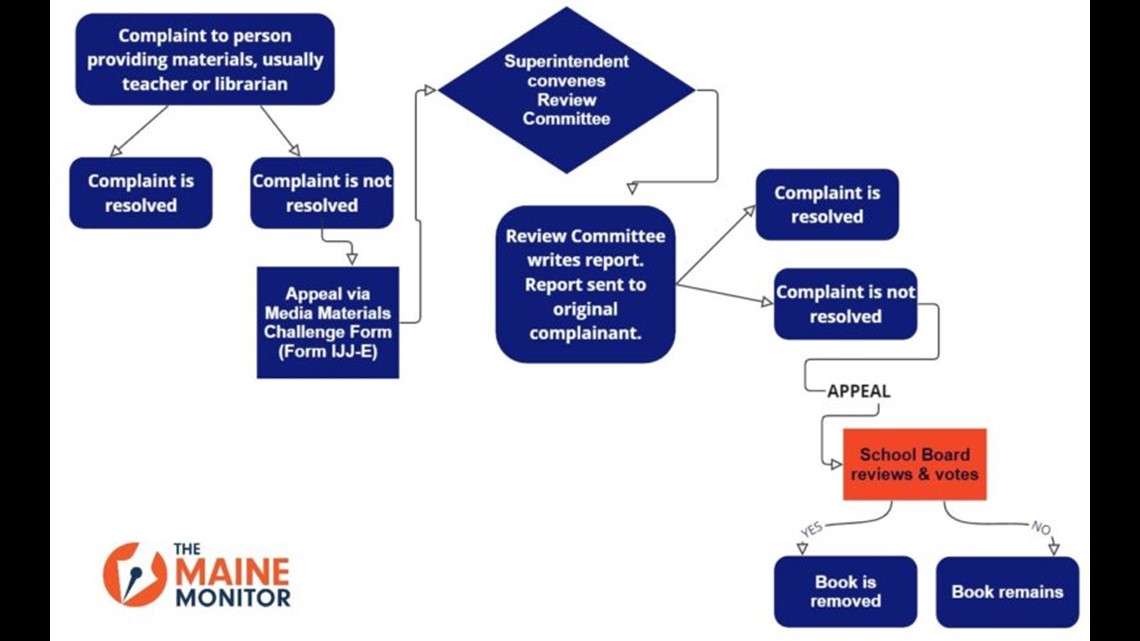

While exact policies vary by district, the Maine School Management Association releases a sample roadmap that districts can amend, update or change to fit their needs. Each of the nine districts that responded to challenges over the past 20 months appear to have followed some version of this sample.

Here’s how it works: If parents or community members want to challenge a book or other academic material, they must first go to the person providing the materials, typically a classroom teacher or librarian. If the complaint is not resolved, the challenger must fill out a Media Materials Challenge Form, also known as the IJJ-E form. A copy is forwarded to the superintendent, who appoints a committee to review the material.

That committee then writes a report, which is released to the original complainant. If the matter is still not resolved, the challenger can appeal to the school board, whose ruling is final.

Quintel said she pursued the challenge because she cares about the future of her town and its schools. She emphasized that she does not identify with a political party and hopes her community becomes more engaged in school issues.

She said she felt disappointed and outnumbered at the school board meeting to discuss removing Gender Queer. There were far more people supporting the book than those who opposed it, she said.

Despite the failed challenge, Quintel has not given up.

“We’re going to continue to fight,” she said, but she has shifted her focus to another cause: school board elections.

Already, the book challenge issue has surfaced in at least a handful of Maine school board races.

Once there is “a more balanced school board,” Quintel said she hopes to see “some of these agendas” scaled back.

Chapter Two: The National Playbook

The boom in book challenges is not unique to Maine. During the first half of the 2022-23 school year, nationally there were almost 1,500 instances of books removed, affecting about 900 titles, according to PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans. This marked a 28% increase over six months.

In 2022, the Office of Intellectual Freedom at The American Library Association tracked the highest number of book challenges since the organization began compiling data more than two decades ago. There were over 2,500 unique titles challenged, a 38% increase from the previous year, according to the State of America’s Libraries Report.

The vast majority of the books were written by or about members of the LGBTQ+ community and people of color, the report noted. Maine largely mirrors this trend, according to the American Library Association.

There are also legislative pushes to curb library materials. This year, at least two bills would have restricted library books in Maine public schools. Both bills failed.

Nationally and in Maine, Gender Queer: A Memoir, the graphic novel about gender identity and sexuality, is the most challenged book. The suggested reader age is 15 and up, according to Barnes & Noble, and 18 and up, according to Amazon.

“I think we are definitely mirroring the national trends,” said Sonya Durney, president of the Maine Library Association.

Challengers often expressed concern about the explicit drawings and descriptions, and argued the book sexualized children in “pornographic” scenes. But librarians and free speech advocates note that the book has won numerous awards, including the 2020 American Library Association Alex Award. It has also appeared on lists such as New York Public Library’s 50 Best Books for Teens. Those experts describe Gender Queer as an age-appropriate book for high schoolers and particularly important reading as students navigate the complexities of gender and sexuality.

One driving force behind the challenges in Maine, Durney said, are nationally circulated lists of books. This makes it easier for community members to challenge multiple titles at once, sometimes without ever having read the books.

“Instead of actually looking at a title and finding something that you personally take issue with, now it seems like they’re just regurgitating whatever examples the national organizations are offering,” said Samantha Duckworth, chair of the Maine Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom.

Rarely, she said, are challenges arising because a child brought a book home and a parent disapproved. The vast majority of the time, parents and community members hear about the books through social media or seeing snippets online.

“It’s kind of like a rolling snowball. (Once it) happens in one district, another district parent goes to look to see if it’s there,” she said.

While concerns about these books might be happening locally, nationally it’s “the same exact quotes that show up over and over again,” said Magnusson, the researcher.

“Parents start with this really legitimate expression of concern — whether they’re deeply religious folks or just worried parents — and then there’s a component of this sort of online radicalization that needs to be looked closer at,” she said.

They often begin these conversations on Facebook, Magnusson said.

A similar phenomenon has taken place in Maine, noted Sue Campbell, executive director at OUT Maine, an LGBTQ+ advocacy organization. “What we’re seeing through these complaints is almost word-for-word the same from one district to another.”

She said this is evidence that at least some complaints are “coming from a more national playbook.”

Some Maine residents appear to be turning to BookLooks.org for support. The Florida-based organization releases book ratings for advised parental guidance, similar to the movie rating system. Users can then click through extensive notes to support the rating, including images of the texts, direct quotes with page numbers, and analysis.

The site is spearheaded by a former Moms For Liberty member, Emily Maikisch, and her husband. And it uses the same rating system shared on the Moms For Liberty Brevard County Facebook page in Florida, according to a 2022 article published on Book Riot, the largest independent editorial book website in North America.

Maikisch, BookLooks’ founder, said she used to be affiliated with Moms for Liberty but left in mid-March 2022 and started BookLooks.org with her husband. It does not appear that Maikisch has posted in the Moms For Liberty of Brevard, Fla. Facebook page since 2022.

Asked if she anticipated the role her site would play in book challenges across Maine, Maikisch said in a written statement, “No. The main impetus in our founding was the lack of accessible information on the appropriateness of book content available to minors so parents can make their own decisions.”

“We don’t get involved in the challenge/activist side of things since our goal is to be a trustworthy source of information, though, often parents share news about what occurs in their school districts,” she wrote.

The site has proved useful to critics of the books in Maine; district leaders and librarians have reported parents and community members reading directly from BookLooks reviews at board meetings or submitting printed copies. But librarians and others say sites like BookLooks.org give community members a resource to challenge books without reading them.

In six of the 19 challenges analyzed by The Maine Monitor, the challenger reported not reading the book in its entirety.

One parent said she read a book’s title — then peeked inside — before filing. Another reported only reviewing the pictures. A third skimmed it and read reviews online before filing a challenge on behalf of a community group.

At least three complaints were signed by a group of people or were filed on behalf of a group. In Bonny Eagle, a challenge of the book It’s Perfectly Normal was filed on behalf of a group called “Concerned Parents & Community Members of MSAD 6.” Another, in RSU 56 for Gender Queer, which was ultimately successful, was filed on behalf of “Concerned Parents of Dixfield.”

Although these “Concerned Parents” groups cannot be easily connected back to a larger national organization, “there is evidence of a continued conversation online about books and trading of lists,” according to Magnusson, the researcher. “Whether or not a concerned parents group that is local to one municipality is connected to a larger parents group doesn’t matter as much as the fact that they are engaged in the conversation that extends nationally,” she said.

Every complaint analyzed by the Monitor — except the two challenging the book White Fragility — mentioned concerns around sex, sexuality, pornography, masturbation or grooming. A number of complainants emphasized not objecting to the texts because of their titles or LGBTQ+ themes, but because of explicit images and descriptions.

One parent wrote, “Public education should have no part of my child’s sexual awakening or social sexual education.”

But some educators argue these texts are essential to students learning about their sexual identity or racism in the U.S.

“Pulling these books out sends the wrong message to our young people,” said Campbell, the executive director at OUT Maine. “They need to know that they matter and that their schools have their backs.”

One review committee in MSAD 52, serving the communities of Turner, Leeds and Greene, wrote in their recommendation, “The book’s values outweigh its faults. The entirety of the book is about the author’s experience and their navigating life as a person having gender dysphoria. The two or three, potentially off-putting, images are intended as depictions of real life experiences and not gratuitous attempts to shock the reader.”

The 19 complaints analyzed by the Monitor ranged from brief form responses to multi-page documents. Beyond the 22 book challenges that have been escalated to the superintendent and school board level across the state, there have been many more informal requests and challenges handled at a lower level.

“Librarians are exhausted and spending a lot of time looking over their shoulder and questioning their purchases,” said Perkinson, the president of the Maine Association of School Libraries. “To have this hanging over us is exhausting and somewhat debilitating. It gets at the heart of our professional expertise and calls that into question when people go after us and call us groomers, and accuse us of distributing pornography and explicit materials.”

One school library media specialist, Kerrie Lattari of York, said people on the internet are trying to slander librarians and educators, questioning their professionalism. Sometimes educators fear for their safety.

“I’ve thought about exiting education,” Lattari said.

But ultimately these situations embolden her.

“If I don’t stay in education and fight, who’s going to?”

Chapter Three: The Look Ahead

Marielle Edgecomb, a high school math teacher in RSU 24 in Downeast Maine, has worked in education for over 30 years. She described her school district as a tight-knit community that values open dialogue and debate. But that began to shift once book challenges emerged.

School board meetings have become contentious, she said, with people in the community yelling at board members because they don’t agree with their decisions. Teachers and other community members watch as school board members are “shredded.”

“If you participate in those meetings that were public, you were subjecting yourself to all sorts of foulness that just saps the energy that’s already been taxed.”

She said this is not a safe place for teachers to be.

“We had people yelling at board members that they were pedophiles,” Edgecomb said. “Can you imagine if a teacher has an accusation like that hurled at them, how they would survive that?”

This spring, a group called “Spotlight on Schools” attended a school board meeting in RSU 24. They were there to present board members with a packet of research they assembled. In it was a list titled “Obscene Books at Charles M. Sumner Learning Campus,” referring to the middle and high school campus. There were 95 books on the list.

Each title was accompanied by a rating from Amazon and one from BookLooks.org. The research packet also contained book reviews, definitions and a rating system, all by BookLooks.org.

Sharing the list of 95 books does not constitute an actual challenge; community members must first challenge the books at the school level before submitting the official complaint form to the superintendent and school board.

Only two titles, Gender Queer and Queer: The Ultimate LGBTQ Guide for Teens, have made it to the RSU 24’s board over the past 20 months; both were on that original list. They were challenged last year by a parent but were unrelated to the list or group, according to her complaint. The two books were initially relocated to a guidance counselor’s office but eventually returned to the library — now in a section for high schoolers. A challenge for a third book on the list, Identical, was filed earlier this year.

Roy Gott, the chair of the Board of Directors of RSU 24, said the process was divisive. Board meetings for the initial two challenges contained some “very heated” discussions and close to two hours of public comment. Community members were split at the first meeting, but more heavily in favor of removal by the second, he said.

The challenge of the third book, Identical, is ongoing. Earlier this summer, Gott noted that the district was struggling to find teachers to serve on a material review committee. Teachers are afraid to do this work, he said. The district has since updated its policy to allow the review to happen privately, and a committee is expected to meet in the early fall.

“In this way we hope to anonymize the other staff members so they don’t feel exposed and can do the work faithfully without fear of retribution from people who might disagree with their decision,” Gott said in a written statement.

He said while he supports transparency in the process, he also needs to protect his staff.

It is not clear how many more challenges parents and community members will file from this list, but Gott emphasized that each is costly and time-consuming.

Edgecomb, the math teacher, considers her community generally respectful and responsive to discourse. That’s why the divisiveness she’s seen over these books has been particularly upsetting, she said.

“In our school we encourage a challenge. We encourage conversation. We can talk to anyone at any level. With a simple ‘Hey, can we talk?’ Except for this issue.”

Note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Kerrie Lattari's name.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.