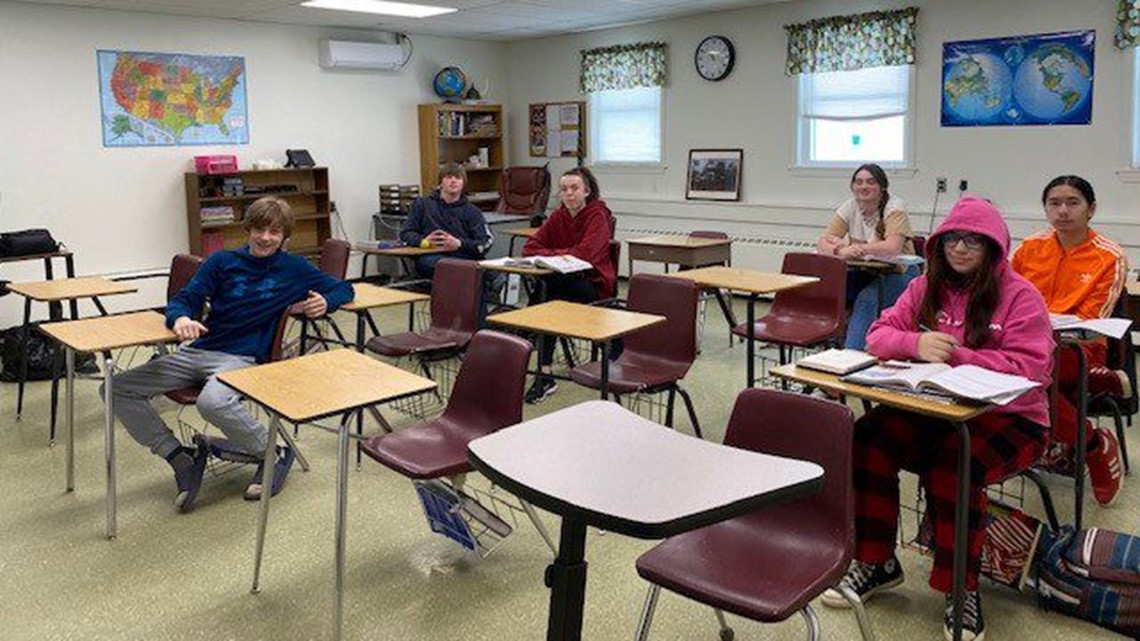

WESLEY, Maine — Not far from the intersection of Routes 9 and 192 in Wesley, you’ll come to a winding dirt road that disappears into a dense forest. Follow it and you’ll find yourself in what might feel like an episode of Little House on the Prairie. Deep in the woods, surrounded by nothing except blue skies above the whining pines, is the town’s humble schoolhouse. One class. One teacher. Four students.

Yet, remarkably, just like the TV episode when the fictional town of Walnut Grove was leveled and all that remained was its little one-room schoolhouse, Wesley’s little school is still standing — despite several contentious battles over the years to close its doors for good.

“The school is all we have left,” said former student, parent, and resident Julie Smith. Choking back tears she added, “We wouldn’t have a community, we’d lose it.”

Last March, the three-member Wesley school board made the controversial decision to close the school after watching enrollment plummet from an historic high of about 25 students in its heyday. Once a thriving logging town of 5,000, all that remains is one school, a convenience store, a church, a museum, a Wyman’s storage facility, and 114 residents. Nonetheless, the sharply divided community reversed the board’s decision at a public referendum in May, voting 39 to 24 in favor of saving the town’s only school, despite an enrollment at that time of merely eight students.

So the school reopened in the fall — by then with only four students.

“You just don’t know what the magic number is enrollment-wise before they close it,” said the school principal, Mitchell Look.

Wesley isn’t the only town facing the tough choice of whether to close its struggling school and send students to neighboring schools. According to Maine Department of Education data released this week, of Washington County’s 34 schools, 20 have enrollments below 100 students, including two high schools. Ten schools have enrollments under 50. The number of low-enrollment schools in both categories is up from the previous year.

In Washington County, the net loss between 2014 and 2023 was 297, with numbers ebbing and flowing from year to year. The steepest plunge came in the 2020-21 school year, with 182 fewer students. After small gains last year, enrollment for the county fell again to 3,192, a loss of 27 students.

However, the county’s premier public-private high school, Washington Academy, has seen its enrollment increase to 349 this year, including private pay and international students, according to headmaster Judson McBrine. The publicly funded enrollment is 278. (Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story was in error on this point.)

Enrollments statewide, however, inched up in 2023, with a total of 173,908 students, 671 more than a year ago. But the trend over the past decade has been steady, sometimes steep declines. Between 2014 and 2023, the state lost 10,369 students, with the biggest drop between 2020 and 2021, when 7,865 students were counted.

The enrollment numbers are apt to change as the state recovers from the pandemic. Maine’s overall population has increased by about 20,000 in the past two years, undoubtedly increasing enrollment in some schools.

Yet smaller schools, and small towns, struggle. It costs more to educate smaller numbers of students spread among numerous smaller schools. In Wesley, for example, according to the Maine DOE, the price per student is $24,114 this year, compared to the state average of $18,000. The annual cost to run the school is $346,302, with roughly a third covering tuition to send students to high schools in other communities because Wesley does not have its own.

According to Scott Porter, the school superintendent for 11 Machias Bay Area districts, including Wesley Elementary, closing the school would only have saved residents a little over $20,000. That’s because the savings would be offset by extra transportation costs and tuition to educate students elsewhere, as well as maintaining the school building that also houses the town clerk.

“I don’t take a position,” Porter said. “I give them the financial data. And in the end, we’re a local control state. So it’s their decision.”

Some residents blame the school’s enrollment woes on superintendent agreements, so-called waivers that allow students from one district to attend another with that superintendent’s permission. Six Wesley students attend Machias schools on waivers. Porter said the school choice movement has made saying no to waivers almost impossible because parents can appeal to the Maine Department of Education and almost always win.

In a written response, a Department of Education spokesperson pointed to Maine’s education law, where the parent’s right to appeal is outlined in state statute. Among other stipulations, the statute says, “A student whose parents live in a school unit of 10 or fewer students are eligible to attend school in a nearby district if the school boards of both units agree.”

“In Maine, decisions about how communities manage schools are made at the local level,” said the spokesperson.

The result often is a school left with fewer resources because enrollment, along with valuations, impacts state subsidies. Local school officials described those subsidies as “paltry” for rural schools, especially Downeast where waterfront properties skew the state’s funding formula. Still, although small schools are costly to keep open, most county school officials interviewed take the numbers in stride, even when consolidation might lower costs.

For example, the coastal Moosabec Central School District has three separate school districts — Jonesport Elementary, Beals Elementary, and Jonesport-Beals High School, with a combined enrollment of only 212. Under School Union 103, they share a superintendent and some administrators, but there are three separate school boards and three separate budgets of roughly a million dollars each.

Lewis Collins, the School Union 103 superintendent and special education director, knows it would be far more efficient to have one budget and one school board, but said there are advantages to independent rural schools.

“I think it’s a wonderful thing,” Collins said. “Our staff and our administrators, our cooks, our custodians, and bus drivers are all dedicated to these kids. And we live in one of the most physically, drop-dead beautiful places in the country.”

Other school officials agreed. They say maintaining small, local schools is the price of doing business in rural communities, where it’s a hardship to bus students to more robust, neighboring schools, sometimes as much as a 45-minute drive away.

A good example is East Grange II Elementary in Topsfield, the smallest of six schools in the Eastern Maine Area School System — AOS 90, straddling Washington and Penobscot counties. Although 10 miles from the nearest gas station or grocery store, East Grange II Elementary is a hub, taking students from several surrounding far-flung towns and unorganized territories, including Vanceboro, which closed its school in 2015.

Despite the “influx,” East Grange II has only 25 students, none in the second or fourth grades. Principal Bethany Kennedy said students are taught in multi-grade classrooms by teachers certified in all grades. The school budget this year was $263,988, costing residents $144,130 after state subsidies. Kennedy said there are occasional murmurs about closing the school, but never any action.

“The community enjoys having this school,” Kennedy said. “And they can use the building and the kitchen, and have functions here too.”

Including Vanceboro, four schools have closed in Washington County over the last 10 years, some for consolidation, others for reorganization. The others were Robbinston Elementary, Cherryfield, and Lubec High School. The trend to close schools, however, is not new. Between 2009 and 2010, 34 schools across Maine were closed, including Columbia Falls Elementary in Washington County.

The controversial decision to close Lubec’s high school in 2010 scattered 37 students as far as 50 minutes away in either direction, to Shead High in Eastport, Machias High, or the public-private Washington Academy in East Machias. With a few blips, Machias High has gained students since Lubec High closed, this year hitting its highest enrollment in 10 years at 178, up another 16 students over last year.

Some residents, still rankled over the Lubec High closure more than a decade later, occasionally mount efforts to reopen the school, most recently in 2019.

“A lot of people were born and raised here and were proud of their school. They want to see their team’s name up there during basketball games,” said the Lubec town administrator, Renee Gray.

Still, others say closing the school also dealt a blow to the town, which until the pandemic surge in population had struggled to attract new residents looking for strong school systems. The town has gained residents since the pandemic, but not many with school-age children.

Officials in the town of Danforth are trying to avoid that pitfall. Not only have they kept their pre-K through 12th-grade school open with only 135 students, but they have also leveraged the school as part of the town’s revitalization strategy.

Danforth and East Grand school officials partner on a host of projects that help high schoolers achieve success after graduation, while also helping bolster the economy of this town of 587 people located in the far wilderness corner of Washington County along the border of Aroostook County.

Most of East Grand’s 46 high school students, through an Extended Learning Opportunity award, either job-shadow, intern, or work paid jobs at a variety of businesses in the town. A new community center and outdoor marketplace pavilion also will provide students with entrepreneurship opportunities, according to Danforth Town Manager Ardis Brown.

“What we look at is the community, and how the community takes care of one another,” Brown said. “Yes, there’s definitely walls up there, but we all work together driving in the same direction to make it a win.”

According to the Maine Department of Education, in the 2022-23 school year, East Grand School scored at or above the statewide expectation in English Language Arts and Math, at 87 percent and 81 percent, respectively. School Principal Margaret White said students are learning skills that land them jobs after graduation, and often take online college courses, all of which provide a leg up in college.

“They still have to earn 24 credits (in high school), but usually by their junior or senior year they either have a vocational placement, a job placement, or go on to college,” White said. “It’s interesting to see how they are developing their own paths.

Even though the enrollment is small, White said students are still provided with every advantage of bigger schools, including music, art, sports, and even foreign languages for those interested in learning. The interaction with the community also helps them develop social skills.

But not all small schools have succeeded in providing such a well-rounded education or are getting the same results. At Wesley Elementary, teacher Mindy Henderson acknowledged that students struggled academically over the last two years, but also said they’ve made substantial gains recently.

“If they’re not grasping concepts, we work on it until they grasp them,” Henderson said. “It’s not like a classroom with 20 kids where you have to move along because you have other kids in the class that need to move along with it. We can take the time that’s needed.”

Currently, Wesley has one student each in first grade, third, fourth, and sixth. One student has special needs and receives additional help from the Machias Bay Area Schools special education teacher, who works with Henderson to fulfill the student’s IEP, the Individualized Education Plan.

Still, the school isn’t able to provide extensive peer socialization or offer formal art and music classes. Sports are only available if parents transport their children 19 miles to Machias, a drive that can take 45 minutes or longer on Route 192, a notoriously dangerous road during winter.

Those are major concerns for the school board, according to its president, Linda Tapley. She and two other members voted unanimously to close the school last year, despite receiving anonymous threats.

“They are our future, and they are entitled to an education that will give them a chance at life,” Tapley said. “I’m not saying they’re not getting a good education. The teacher does everything she can, but they’re not getting a well-rounded education. And we can’t give it to them right now. And that hurts.”

The failed effort was the third attempt to close the school since 2008, with several other attempts over the past 30 years, according to Smith, who fought each time to keep the school open. She, her two brothers, and three children attended the current Wesley school, built in the 1970s, and before that she attended the one-room schoolhouse on Route 9 that is now the town’s history museum. Smith grew up in one of the decommissioned schoolhouses, where she had a chalkboard in her bedroom.

There were originally four one-room schoolhouses tucked among the woods, serving the community during Wesley’s boom time as a logging town. Smith said her teachers took them on field trips, teaching them the town’s history. Signed clay tiles and quilts line the school walls, commemorating generations of students. Smith said at Wesley, where there are only a few students per class, every student matters, history matters.

Wesley resident Sandy Parsons, a teacher in the Machias School District, agreed. She was one of the 39 residents who voted to keep the school open. Before his unexpected death in 2021, Parson’s husband Stephen Copel was a teacher at Wesley, where he worked with special needs students and developed innovative programs. Parsons said Copel had a vision for what the school could be.

“If they could all hold hands and get together, have maybe something like a vision session, they would be able to move things around a little bit for more resources,” Parsons said. “It’s such an asset. Someday there are going to be families that want to move here. Maybe not next week, but when they do there will be a school. Once it closes, it’s never coming back.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story included incorrect figures for Washington Academy.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.