PORTLAND, Maine — Ask survivors of sex trafficking or those who arrest and prosecute predators—they'll tell you the same thing: Maine’s system is broken. Eradicating sex trafficking and helping victims become survivors just doesn't seem to be a priority in our state.

"The criminal justice system is a mess," Molly Fox, a survivor of trafficking says. "We would just rather plea things down so they don't go to court.”

"I knew the system was broken and I couldn't fix it," Steve Webster, a retired South Portland Police Department detective who worked sex trafficking cases for years, says. "I said, 'I have to at least try to get them to a place where they're safe.'"

Maine is a "source state" for sex traffickers, retired FBI agent Pam Flick says. They come to recruit or seduce vulnerable women and girls into what they call "the life."

The half-mile stretch of Congress Street between the Greyhound station and Neal Street is known in the sex trafficking world as "the track.” Women and girls hang out there, often during the lunch hour, waiting for what they call "a date.'

At times they openly signal to passersby. Some cars circle the block several times before turning up a side street and pulling over.

Down the hill are "trap houses," where a dealer will offer them drugs or a shower before they head back for another date.

Whether a woman is directly trafficked by a pimp or exploited by a John is a legal technicality, Webster says.

According to experts, Maine laws addressing sex trafficking are weak and there simply isn't enough will among state officials to strengthen those laws … or to fund adequate services for survivors.

Steve Webster says he refused to bring victims to shelters, "because what are shelters? Those are the best places to groom and locate potential trafficking victims."

Police say they have moved away from treating the victims as criminals.

"A lot of our focus is on the demand side and on having an impact on the people that are actually providing and putting these women into the circumstances that they're in," Portland Police Chief Frank Clarke says.

Clarke said his department has arrested dozens of men in recent years for engaging a prostitute.

Androscoggin County Assistant District Attorney Nate Walsh says that although officials shut down backpage.com, a site notorious for solicitation, other websites are worse. He showed us one from overseas advertising women he's seen recently on the streets in Lewiston.

As for assisting victims, "If we come in to tell someone that we can help, we have to have the means to help," Walsh says. "We can't come in with empty gestures, so it's having the resources to really meaningfully address some of the difficulties we're seeing in the streets."

"The hours to help extract someone from 'the life' are overwhelming, particularly when a victim is convinced to enter a detox program or move to a shelter, only to find there's no bed," he says.

In 2007, a new law amended the definition of kidnapping and criminal restraint to include conduct that constitutes human trafficking. The law also allowed for civil remedies and forfeiture of assets in connection with these crimes.

Then-Attorney General Janet Mills, in accordance with another provision of the new law, hosted a Working Group on Human Trafficking.

In 2010, The Working Group report determined that many in law enforcement were didn’t truly understand the nature of this type of crime. In response, they helped develop a curriculum for The Maine Criminal Justice Academy and the curriculum is now part of the mandatory field training for all law enforcement officers.

NEWS CENTER Maine wanted to know more about what The Working Group has accomplished in recent years.

Now-Governor Mills directed us to the Attorney General’s Office. A spokesman for Attorney General Aaron Frey did not tell us when the Working Group last met, that the next meeting has not yet been scheduled and that the group meets “at least annually”

The Maine Coalition Against Sexual Assault (MECASA), hosted the Working Group -- until it disbanded a number of years ago. Jess Bedard of MECASA, says the group was inactive for several years before recently reorganizing and meets "intermittently."

Cumberland County District Attorney Jonathan Sahrbeck would like to see longer sentences for those convicted by the state. In Maine, the maximum sentence for someone convicted of aggravated sex trafficking is 10 years. But someone convicted of the same charge in federal court faces a minimum sentence of 15 years.

The Maine Criminal Code was amended to specifically define “Human Trafficking.” It is now a Class B Felony to traffick a person under the age of 18 or to compel prostitution by using force, threats, extortion or withholding alcohol or drugs to an addicted person or withholding government IDs or threatening deportation.

A law enacted in 2014 allows victims of sex trafficking to mitigate charges of prostitution. It also increases and mandates fines for sex trafficking and allows victims to access funds from the Victims Compensation Fund Administered by the AG’s Office

IN 2018, Mills used settlement funds to establish the state's first emergency shelter-safe house for victims of human trafficking.

Experts in the field say these are insignificant changes. No bills have been introduced in the current session of The Maine Legislature, specifically targeting Sex Trafficking.

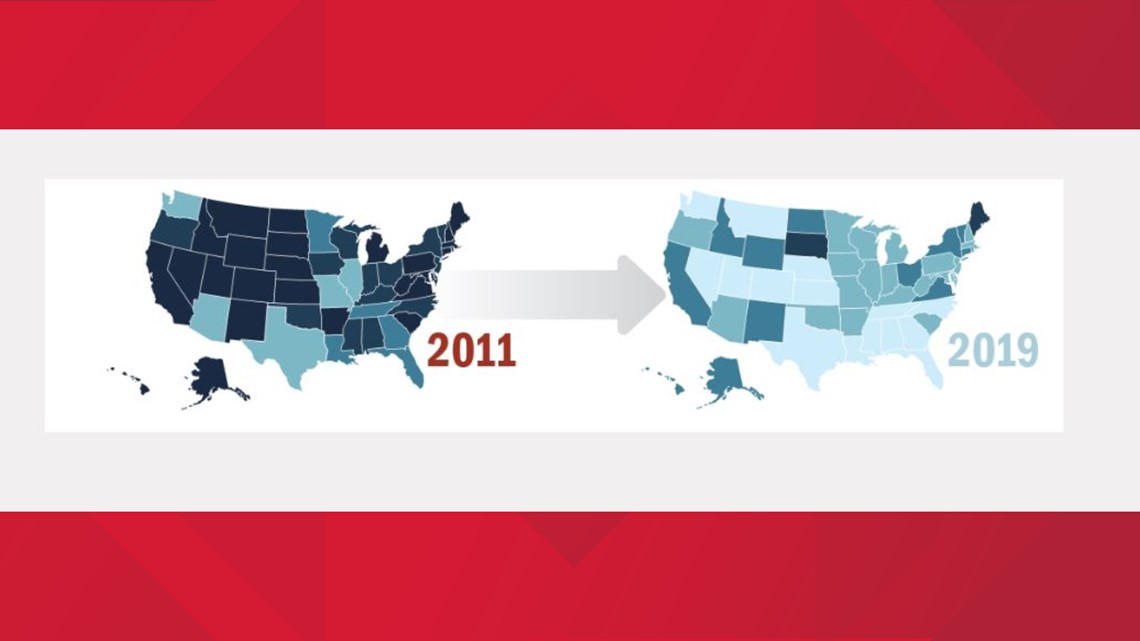

In 2019, Maine received a "D" on an annual report card issued by the organization Shared Hope International, which grades the effectiveness of state laws regarding trafficking of minors.

Worse, Maine had received a grade of F in 2011, but unlike most other states, saw little or no improvement in prevention due to reducing demand, providing appropriate responses to victims, establishing protocols and facilities for victims, mandating appropriate services and shelters and incorporating trauma-reducing mechanisms into the justice system, the report states.

So, when it's time to prosecute, state officials often turn to the feds to get justice.

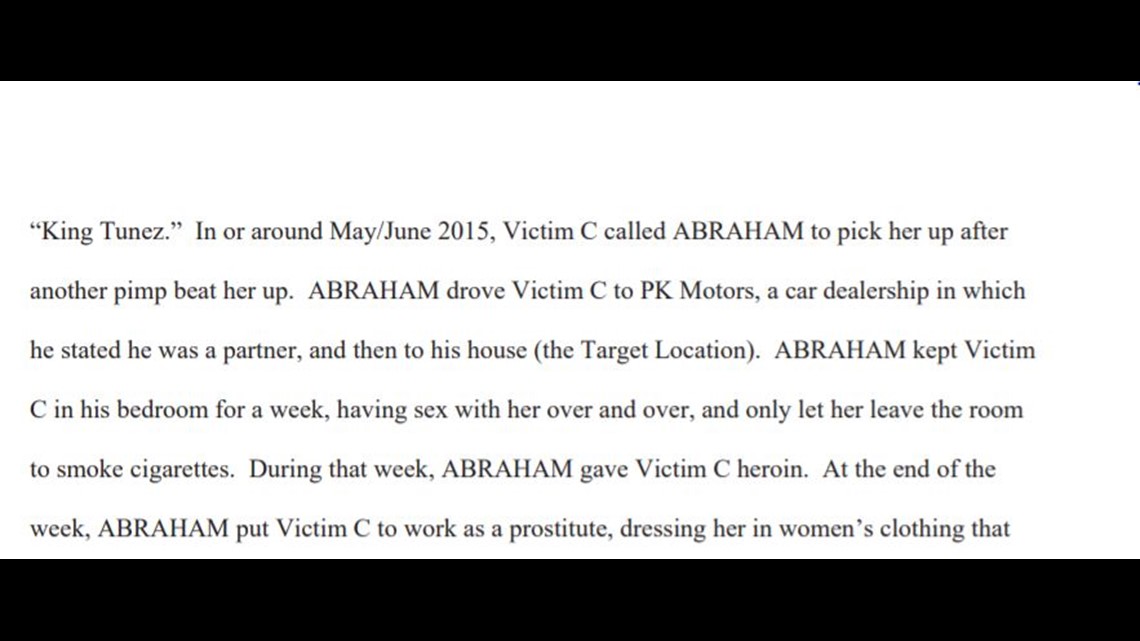

During just three months in 2019, men from Boston, New York City, and Biddeford were convicted in federal court of trafficking five Maine women and a 15-year-old girl from Maine.

One trafficker used a lit cigarette to burn a hole through his victim's cheek.

Sentences were as long as 26 years. One of those men, Reginald Abraham, faces 15 years to life in prison when he's sentenced later this month.

Even more alarming is the lack of comprehensive resources available to survivors.

A day or two wait between leaving a detox program and finding a bed in a residential program, for example, often sends a survivor back to the street.

"If we were more victim-focused and we had agencies that actually did something instead of talking about doing something, that would be great," Webster says.

Preble Street Resource Center in Portland provides case management services to survivors who can prove they're victims of "severe trafficking." Nearly $2 million in grants fund the center. But the city's shelters offer only two beds designated for survivors.

It's a problem even retired FBI agent Pam Flick couldn't solve.

"Oftentimes you're stuck trying to find a suitable place for this person," Flick says. "Your first thought is, 'We'll put them up in some hotel room.' So now you're putting them in the exact same place that they were traumatized before, so does that really help? I mean, you're in desperate need ... if Preble Street doesn't have a bed available, there are a couple of facilities in Lewiston and Auburn, but they're few and far between and it's difficult sometimes."

But at least one program is making a difference. CourageLIVES—formerly known as Hope Rising—in Penobscot County is a residential safe house that offers beds to five survivors for up to two years. It also connects them to services including medical care, detox and substance abuse recovery, outreach and outpatient counseling.

"If you had more places like CourageLIVES and Amirah down in Massachusetts, which ... builds self-esteem, teaches life skills, [and] gives them a sense of worth back that many of them have literally never had in their lives," Webster says they’d be more successful.

Tricia Grant, a survivor of sex trafficking, is program manager at Sophia’s House, a home for survivors in Lewiston. Grant says education is critical to addressing the problem.

"People needed to intervene before I was ever trafficked," Tricia says. "This is the case with the majority of us as survivors and thrivers … so why not start there now with our youth and with educating our children now on who they are and creating their identity before that trafficker has any input in their lives."

Survivor Kasie Robbins knew a girl who grew up with "everything she needed," but still ended up being trafficked.

"It wasn't for lack of resources, but because [her parents] were so overbearing and on her Facebook and in her business ... that's a dream for a pimp," Robbins says. "That is a dream. All's they need to do is get you liquored up, maybe feed you a line, maybe not even, maybe just have sex with you the right way, to be real, and you're automatically, 'Wow, this is so much fun, this is great.' She literally like moved out of state with this man and he's now trafficking her."

Cary Nason, director of CourageLIVES, says traffickers target victims' unmet needs.

"If someone’s homeless, they offer the home," she says. "If someone needs a sense of love and belonging, they offer it. If someone needs a job, they offer it. They offer something better than what it currently is. And when you don’t have what you need in life, it’s rough. We all do what we need to do to get by and survive – it’s not any different for someone who has been trafficked – they’re trying to live too, just that their experiences have been horrific, atrocious."

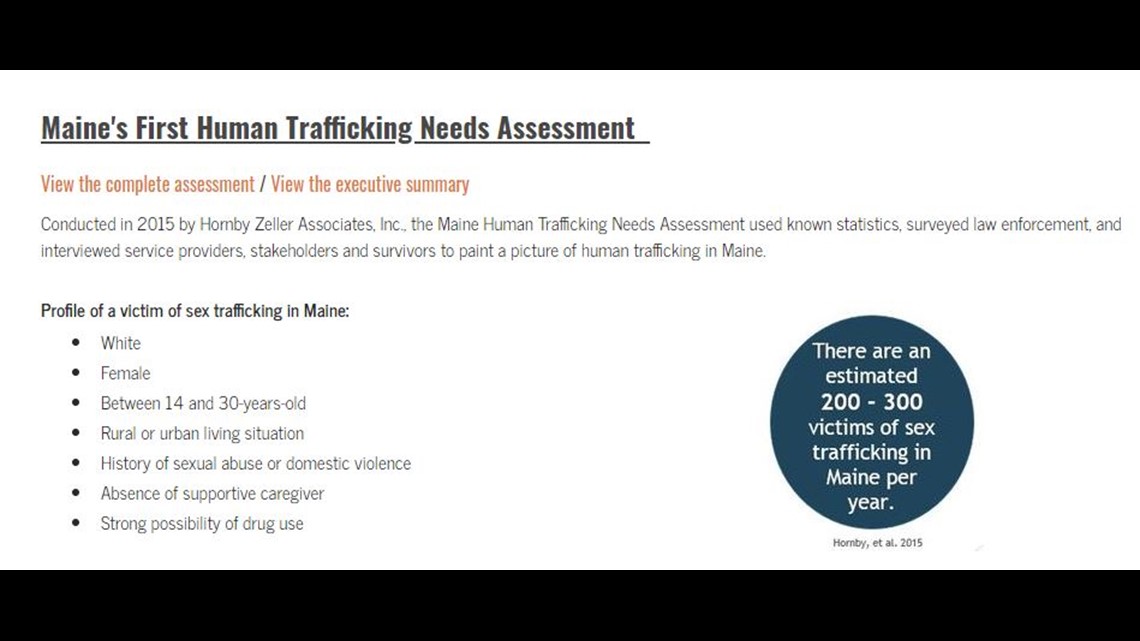

Flick says she's met women and girls as young as 13 and as old as 58, from all over the state, who were trapped into trafficking.

"There’s a lot of trolling on the internet, a lot of Facebook trolling," she says. "They’re looking for weaknesses, and they’re very skilled at their craft."

Flick says she worries for her young daughter. She says she talks openly with her, tells her about predators, and she says 'no' to Facebook.

"You use your sixth sense," Nason says. "If the hairs on the back of your head tell you that isn't a good idea, it probably isn't."

Webster would like the state to designate a sex trafficking task force modeled on the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency, with a state-funded director and designated agents from local law enforcement.

But, not long retired and still overwhelmed by the tragedy he saw on the streets, he isn't optimistic that addressing sex trafficking is a priority for our state any time soon.

"I’ve always said if it was the governor's daughter that was sucked into sex trafficking, guess what, we'd have a goddamn task force, all right," he says.