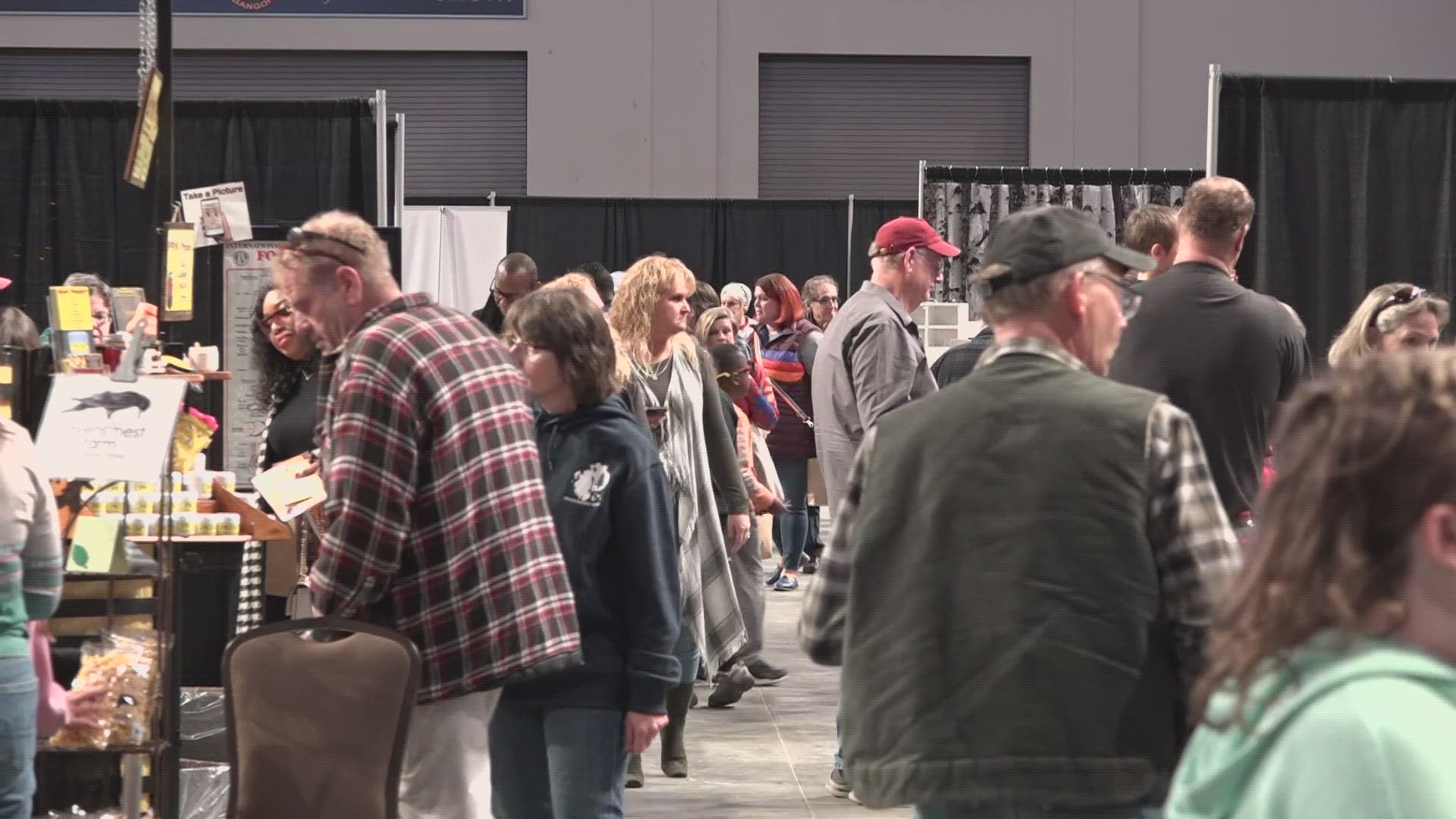

BANGOR, Maine — As the fields of Maine frost over, farmers and food producers gathered in Bangor Sunday for the Maine Harvest Festival—a celebration of the end of a productive, but complicated, fall.

The event was sponsored by the Maine Potato Board, whose executive director Don Flannery is content with this year’s crop of spuds.

"Yields are average and quality I think is good," Flannery said Sunday.

But despite this (relatively) positive news, farmers, Flannery says are hurting.

"We have seen dramatic increase in input costs," Flannery added. "instead of that gradual increase on line charts you're seeing a peak."

As a result of inflation and damages to the global supply chain—caused in part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—the cost of doing business for Maine farms is soaring.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the total money spent on growing crops and raising livestock hit an all-time high this year, at $460 billion.

Beyond tightening margins for farms already locked into commodities contracts at a fixed price, food producers are shouldering some of the burden.

"I feel like everything is just rising, that’s just how it is right now," Ato Swann said. Swann makes blueberry jams using blueberries bought from farmers in Washington County.

These pressures, in turn, are raising the price of goods for consumers, as Carrie Whitcomb has had to do when selling products from her business, Springdale Farm Creamery, in Waldo.

"We got to find a happy medium so we’re not pricing ourselves out," Whitcomb said Sunday.

Still, perhaps as a marker of the strange ways of the United States economy, where spending is high despite high-interest rates, Whitcomb and Swann both haven't noticed an exodus of customers, even after raising prices to preserve their bottom line.

"Business has been steady," Whitcomb added. "We’re still in the growth phase."