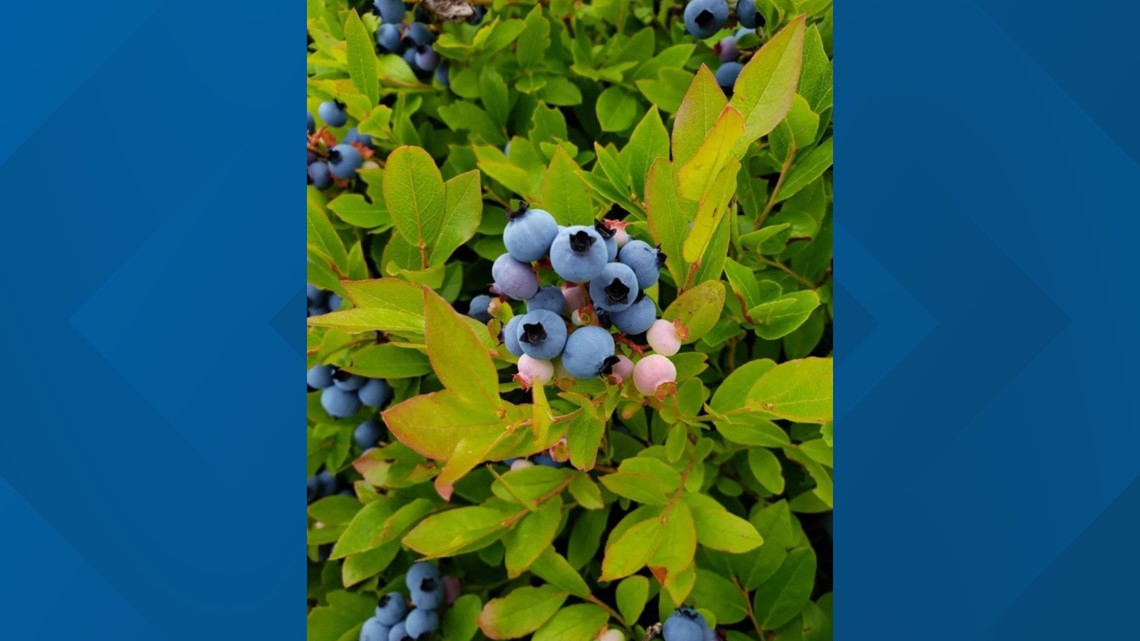

ROCKPORT, Maine — Paul Sweetland brings a bucket-like object with him to work on a blueberry farm in Rockport — not to collect Maine’s hallmark fruit, but to protect his head.

That’s because this farm is a little unusual: Looming over the narrow rows of wild blueberries are 8-foot-tall solar panels. It’s both a farm and a power plant, which means he needs a hard hat.

“Some panels are above my head and some are down at my head level. Some end up down closer to my waistline. But the edges of the panels are such that if I didn’t wear a hard hat, I could end up injuring myself,” Sweetland told The Maine Monitor.

The hard hat is a minor inconvenience for Sweetland, but is emblematic of a broader question that researchers have been studying on this farm: How can agricultural lands support both crops and solar panels without hurting the other’s bottom line?

Solar developers and agriculture researchers from the University of Maine have been studying the issue for two years at this 12-acre, four-megawatt project in Rockport.

The so-called dual-use array, built by Boston-based BlueWave Solar, is operated by Navisun, a Massachusetts solar power producer that distributes the electricity to Central Maine Power’s energy grid. Sweetland manages the blueberry fields on behalf of the landowner, who leases the land to Navisun and receives a share of the blueberry profits.

When the Rockport project launched in 2021, it was touted as the largest dual-use solar farm in the country, and seen as a litmus test for the viability of future initiatives.

The ongoing development of such projects comes as Maine is chasing both ambitious renewable energy goals and seeking to preserve agricultural lands for local food production. The state hopes to rely on in-state producers for 30 percent of food consumption by 2030, up from 10 percent in 2020.

But Maine has limited lands suited for agriculture, The Monitor previously reported, and a large portion of solar projects are on agriculturally significant soil, suggesting the need for agrivoltaics, which is the use of land for agriculture and solar power generation.

To Lily Calderwood, a wild blueberry specialist at the University of Maine, a preliminary takeaway from the study in Rockport is that the way the solar array is configured makes farming difficult and constricts blueberry production.

In addition to wearing hard hats, farm workers must use smaller, specialized equipment to access the bushes. Sweetland opted for a new four-wheeler instead of a tractor, for example, and most work on the bushes is done by hand.

The big question is whether the blueberry bushes can produce enough to turn a profit. After analyzing the 2022 growing season, Calderwood said it doesn’t look promising; when it comes to the berries, the costs outweigh the benefits.

Shade from the solar panels is significantly reducing blueberry yield. Bushes planted in shaded portions underneath solar panels produced just 9 percent of the blueberries compared to bushes planted in rows between panels.

Wild blueberries “can handle some shade, because when they’re grown in the woods they are shaded and they still grow,” Calderwood said. But when sunlight levels dip too low, blueberries put more energy into producing leaves rather than fruit, so they can catch what little light may filter through to the understory.

Bushes with more leaves require more pruning, Calderwood said, noting that the shaded areas also saw lots of weeds and a high incidence of disease.

“At the end of the day, it’s not economical for a blueberry farmer to do dual-use at the moment because of the shading and all of these logistics,” Calderwood said. “They’re not even going to make money on the field because (the plants) are shaded.”

Still, there were bright spots among the findings.

A principal aim of the study was to determine what impact installing the solar panels had on the blueberry plants. To measure this, researchers worked with BlueWave to designate three areas with varying levels of construction precautions.

In the “standard” area, no precautions were taken; in the “mindful” area, construction and foot traffic were limited, and equipment could only rotate 90 degrees; in the “careful” area, protective coverings were placed over the blueberry plants, with even more limits on equipment rotation and foot traffic.

Although disturbance was obvious in the beginning, Calderwood and Sweetland said it’s now hard to tell which area received which treatment.

“We didn’t see any statistical difference between those treatments, meaning that the blueberry recovered well,” Calderwood said.

She suspects that’s because construction did not disrupt the soil profile at the depth of the blueberry’s roots, leaving both the plant and soil intact.

“The point was really to look at the installation impact,” Calderwood said. “So in that respect, it was great. Installing it with all this huge equipment does not have a huge impact on the field itself, but the shade changes the whole system.”

The project backers are energized by the preliminary results, which they said will help guide similar projects they’re pursuing in Maine and elsewhere.

Jesse Robertson-DuBois, director of sustainable solar development for BlueWave, said his company’s primary concern was how the crops fared during construction.

“What we’re trying to do is protect the crop, keep those perennial plants alive, and then learn … the shading impacts and the construction impacts of that design,” Robertson-DuBois said.

BlueWave is already using the Rockport results to guide a blueberry project in Massachusetts.

The company plans to introduce wider rows and build solar panels on an axis that allows them to pivot and track the sun throughout the day, letting in more light for plants.

One of Calderwood’s key takeaways is that future projects may have to consider which activity to prioritize: solar energy production or agriculture.

Robertson-DuBois said building a solar farm suited for agriculture is more expensive than other solar projects: It requires more cable to space the modules farther apart and taller mounts to give farmers room.

“All of these add hard costs to the project, even setting aside any operational efficiencies and that type of thing,” he said, noting that state incentives can help offset added costs.

Massachusetts is ahead of Maine in this department, Robertson-DuBois said. Massachusetts offers qualifying agrivoltaics projects a base compensation rate of $0.14 to $0.26 per kilowatt hour of electricity produced.

“We don’t have something like that in Maine at this point,” he said. “So we’re a little more constrained.”

In 2022, an agricultural stakeholder group recommended that Maine adjust tax incentives for dual-use projects and streamline the permitting process.

BlueWave is still pursuing dual-use solar projects in Maine, but rather than focusing on crop production, is working on plots where the land under panels is maintained as wildlife habitat or used for sheep grazing.

“We see enormous potential to both keep land in agricultural production but also to achieve these kinds of ecological benefits,” Robertson-DuBois said.

The technology is there, he said, but there are two main challenges.

One is financial, figuring out how to offset the costs of the specialized arrays. The other is cultural, navigating pushback from communities concerned about solar farms disrupting their views.

“The question becomes, are individuals and communities willing to embrace the renewable energy transition, even when it results in a change in their view? That’s the crux of the issue,” Robertson-DuBois said.

From the perspective of the Rockport array’s operator, Navisun, the project has been a success — even if the blueberry fields aren’t as productive as they would be in open sun.

Stephen Campbell, Navisun’s chief operations officer, said the array’s energy production has been significant and the coordination between Navisun, Sweetland, Calderwood and others working on the fields has taught the company how to communicate effectively and keep both operations buzzing simultaneously.

Rockport is the company’s first venture into agrivoltaics, and the significance of managing an active power plant mere feet above an agricultural field shouldn’t be lost, he said. Certain safety protocols have to be followed that farmers don’t otherwise have to think about, like Sweetland donning his hard hat.

“We want to cohabitate in a situation where we’re both benefiting from this,” Campbell said.

He added that a few decades down the line, when solar arrays may be retired, that land could open up to full-scale agricultural production again. In the meantime, farmers can make money by leasing their land to companies like Navisun.

Researchers will continue to keep an eye on the Rockport project.

David Specca, the agrivoltaics research lead at Rutgers University, said he is interested in seeing what happens to the farm a few years from now.

“We need to give it a little bit more time and see what shakes out,” Specca said. “Farmers are pretty resourceful. If there’s something that maybe has a low-tech fix, they might figure a way around it.”

UMaine researchers will keep visiting the Rockport farm as they finish the last year of their study. Because blueberries are a perennial crop and the last boon came in 2022, they’re expecting more growth this summer.

“I think this is a great place to start,” Calderwood said. “We’ve learned a lot from this experience, from the data we collected but also from understanding how solar arrays are installed, and how many different companies are involved.

“It’s a whole different world.”

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.