ELLSWORTH, Maine — Suspended Ellsworth attorney Christopher J. Whalley was disbarred Monday following a state disciplinary investigation for allegedly transferring more than half of a client’s estate to his law office’s bank accounts.

Whalley had been ordered to immediately stop practicing law last February amid a state investigation into his alleged “misuse, or outright embezzlement” of client money, according to court documents. He appeared virtually at a hearing with his lawyer Walter McKee and signed an agreement Monday morning acknowledging the misconduct, or that the state could have proven the allegations had a scheduled two-day hearing taken place, McKee said.

At the center of the controversy was the estate of Wilbur Knudsen, a Milbridge man who died in October 2018. Whalley is accused of moving nearly $190,000 from the deceased man’s $378,000 estate to bank accounts in Whalley’s control.

Knudsen intended for eight gifts of $10,000 each to be distributed to family members, friends and a local animal shelter, according to his will. The remainder of his estate was to be sold and divided between two grandchildren, which included setting up a trust to help one grandchild pay for college.

“He said he felt they were the ones that could truly use it financially,” Wendy Jipson, a family friend and neighbor of Knudsen, told The Maine Monitor.

Jipson said she was pleased with the disbarment.

“I’m pleased because there’s not a chance he could do this to another,” she said.

Jipson helped care for Knudsen near the end of his life — taking him grocery shopping and to the bank. She said she was at his bedside when Knudsen signed his final will, which Whalley prepared, making himself the “personal representative” of the estate with the power to distribute Knudsen’s assets after his death.

Much of the money appears to have been paid to Whalley instead, according to court documents filed by the Board of Overseers of the Bar, an independent judicial agency that investigates and prosecutes attorney misconduct in Maine. Checks totaling $99,022 were eventually written to the beneficiaries of the will and creditors of the estate, according to court documents.

The board of overseers filed seven counts against Whalley accusing him of violating the rules of professional conduct, including allegedly making false statements, taking an unreasonable fee, failing to keep a client’s property separate from his own, making advance payments to himself, and failing to diligently perform legal services or to comply with the Maine Probate Code. Whalley denied the alleged misconduct through his lawyer, McKee, in June.

“This is certainly a black mark. We would recognize that but at the same time it’s not the only thing that is the measure of a person. (Whalley) did a lot of good in Hancock County and many counties over his 31 years. Certainly this event was unfortunate,” McKee told the court Monday.

McKee said the agreement was not an admission of criminal conduct. A spokeswoman with the Office of the Maine Attorney General confirmed the agency is investigating Whalley.

Whalley and his lawyer declined the Monitor’s request for an interview.

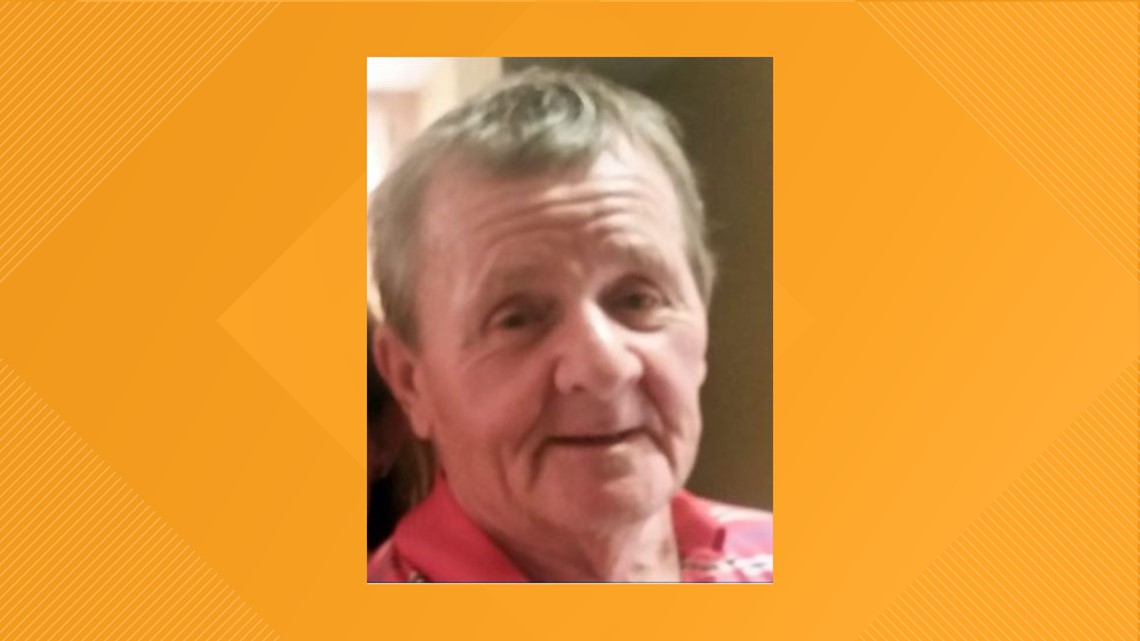

Knudsen, a retired millwright, split his time between Milbridge and Port Charlotte, Fla. He was short with a big mustache, a “quirky little sense of humor,” said Karen Schevenieus, who cut his hair and whose father was one of Knudsen’s friends.

Shortly after Knudsen’s death at age 79 in October 2018, Jipson gave the deed, checkbook and bank statements to Whalley at his request. She also agreed to look after Knudsen’s house each week to save the estate the cost of Whalley driving the 31 miles from Ellsworth to Milbridge to check on the home.

The home’s heating oil ran out in November 2018 and it took Whalley until January 2019 to approve Jipson’s requests that more oil be delivered, she said in a complaint to the board of overseers and an interview with the Monitor. When the boiler wouldn’t start, it took several more weeks for Whalley to approve a repairman to come, she said. By then the walls inside the home had cracked from the extreme cold. In May, seven months after Knudsen’s death, Emera Maine disconnected the electricity because bills had not been paid.

“This isn’t how (Knudsen) operated. When he got a bill, he paid it that day,” Jipson said in an interview.

Whalley met Jipson at the house in January 2019 and appraised the value of the contents at $2,000, according to probate records. He sold it all to Jipson except for a few items in the garage.

Jipson said she was told it would take three months to execute the will and distribute the money to the people in the will — including her own father, Everett West. But three months quickly turned into five months. Jipson told the Monitor her phone calls went unreturned and she didn’t see Whalley again until making an unannounced visit to his office in Ellsworth on March 29, 2019.

“That’s when I asked him, ‘Why now, Whalley? Why are we waiting now? And he knew, of course,” Jipson said in the interview. “My interest the whole time was not just because my dad is in the will. My interest is because these other people want their money. (Knudsen) left it to them — that was his last wishes — and I told him when I became his power of attorney, I would take care of him. And I’m still working on taking care of him.”

Jipson said Whalley promised during their meeting that he would write the checks the following week.

Whalley instead paid himself $69,000 between June 2019 and August 2019 from Knudsen’s estate, according to the accusations filed by the board of overseers in court. Knudsen’s case file from that time period contained two letters that Whalley wrote to creditors and one letter from the county probate registers, which Whalley didn’t respond to at the time, according to court records.

In total, Whalley allegedly paid $189,375 to his law office and trust accounts with Knudsen’s money, according to a board analysis of banking records. The timing of the payments “is not consistent with any regular ‘billing cycle’ ” and the frequency of the checks written to Whalley’s law office is “not consistent with legitimate payments” for services rendered or expenses incurred, according to information filed by the board of overseers in support of further sanctioning Whalley.

Whalley wrote dozens of checks in round amounts — ranging from $500 to $8,000 at a time — to his law office, which was inconsistent with payments for services and expenses he billed to the estate, according to the board of overseers complaint. Whalley wrote additional checks ranging from $2,000 to $30,000 from Knudsen’s estate to his own trust account.

Meanwhile, Whalley neglected Knudsen’s other assets that were to be divided between two grandchildren. His largest assets — the house — sat vacant for nearly two years. A close friend reported Whalley to the board of overseers in June 2019.

Then, Jipson reported Whalley to the board of overseers as well on July 3, 2019, according to a copy of the complaint provided to the Monitor that noted the deteriorating condition of her late friend’s house.

“This home sits directly on the ocean and is worth over $200,000. It’s an absolute shame to watch it be neglected, and to know that Wilbur would be heartbroken at the shape it’s in. It was his pride and joy and it gave him such joy and pleasure to sit on the deck and watch the lobster boats in the bay. Mr. Knudsen’s last wishes are not being carried through. He trusted Mr. Whalley to handle his affairs and Mr. Whalley is not fulfilling his duties and obligations to Wilbur. Something needs to change,” Jipson wrote to the board.

Court records show the board of overseers opened an investigation in 2019 but agreed to delay taking action. Through 2020 and into 2021, Whalley asked for extensions to finish his work on the estate. Then he stopped responding and in April 2021, the board of overseers reopened the investigation, records show.

This is not the first time Whalley has been investigated by the board of overseers.

Whalley was suspended for three months in 2003 but was allowed to continue practicing law as long as he agreed to be monitored by an attorney for a year. A judge ruled that Whalley had engaged in the “improper handling of client trust funds” during a case where he simultaneously represented multiple people and businesses from whom a woman had stolen tens of thousands of dollars, according to board records.

Whalley was later reprimanded — the lowest tier of public discipline — in 2005 for having a conflict of interests and again in 2008 for his lack of attention to a time-sensitive divorce case, according to board records. The records also reveal Whalley was also given warnings in 1995, 2000, 2001, 2005 and 2015.

In 2007, Whalley was suspended again — this time for 30 days — for neglecting a client’s case and for not diligently pursuing another matter. He was again allowed to continue practicing law as long as he agreed to be monitored for another year.

Whalley was suspended for a third time in April 2021, after he was found to have forged a client’s signature on a document submitted to the court years earlier, Superior Court Justice Ann Murray ruled. The suspension was supposed to last a year, though again he was allowed to continue working as long as he participated in a psychological evaluation and treatment.

By the time Whalley was suspended in 2021, the board of overseers had already received complaints from Jipson and another person about Whalley’s handling of Knudsen’s estate.

While still on probation, the board of overseers requested in February that the court immediately suspend Whalley from practicing law. The state didn’t notify Whalley or his attorney prior to sending the request.

“… The board has determined that exigent circumstances exist in this case due to attorney Whalley’s extensive prior disciplinary history, and his continued access to substantial amounts of client funds that are susceptible to misappropriation or embezzlement in the event he receives prior notice of this request for his suspension,” the board wrote.

The court granted the emergency request. During his fourth suspension in nine years, Whalley would finally be ordered to stop practicing law while the state investigated.

Older adults in Maine collectively lose at least $4 million annually as a result of financial exploitation, according to an analysis of Adult Protective Services and Legal Services for the Elderly cases.

The majority of abuse and financial exploitation is done by family members, who may take money from bank accounts, get deeds transferred to themselves or evict older family members from their homes, said Jaye Martin, executive director of Legal Services for the Elderly, which provides free legal services to Maine residents age 60 and older when their basic needs are at stake.

Exploitation by a financial advisor or trusted professional is far less common, she said.

“All of this is really hard for people to picture and imagine. I think all of us want to think of it like, ‘Oh, those doggone romance scams’ or grandparent scams or all the anonymous scamming, which is very predatory and very awful, but it isn’t doing near the harm that the familial exploitation is doing,” Martin said.

For this reason, Martin recommends that seniors consult an attorney when writing wills, healthcare directives or documents giving a person power of attorney. Lawyers are beholden to professional rules of conduct and ethical standards, which if broken have consequences, she said.

Martin declined to comment on any specific case. In general, Martin said it can still be considered financial exploitation if the person is dead, because the final wishes for the assets aren’t being honored.

Martin co-chaired the Elder Justice Coordinating Partnership that was formed by Gov. Janet Mills, which brought together private and public groups to evaluate Maine’s response and prevention of elder abuse. The group released a report in December 2021, which was to be a “roadmap” for how the state could improve.

Among the “top priority” recommendations were that Maine assign a dedicated elder fraud prosecutor within each district attorney’s office to make it more likely that cases were pursued. They also recommended that there be more forensic auditing resources to support law enforcement in investigating financial exploitation cases.

In response to the board of overseers case against Whalley, the court assigned a lawyer to take control of client files and computers at Whalley’s law office. The lawyer reported to the court earlier this year that he had spoken with the attorney general’s office and Maine State Police, court records show. Jipson also told the Monitor that she had been contacted by a state trooper about Whalley.

“The case is under investigation by the Office of the Attorney General,” Danna Hayes, a spokeswoman for the agency, wrote in an email to the Monitor.

What happened to Knudsen’s estate was sad, unusual and the result of a “perfect storm” of problems, said Carlene Holmes, who has worked as register of probate in Washington County for 24 years and plans to retire on Jan. 1.

The register office for the Washington County Probate Court has three employees, including Holmes. At three different occasions, there were job vacancies and new people who needed to be trained while Knudsen’s case was open. The COVID-19 pandemic also shut down the office and forced them onto new laptops and new technology.

“We couldn’t have been any busier,” Holmes said.

Holmes sent letters to Whalley asking him to complete necessary tasks, like notifying Knudsen’s heirs of the case. Whalley had a string of excuses, she said.

Knudsen’s friend, Dale Schevenieus, wrote letters, submitted editorials and called Holmes about his concerns with how Knudsen’s estate was being handled. He witnessed Knudsen sign the will, but wasn’t named as a beneficiary so he had no authority to intervene in the probate case, Holmes said. The court’s hands were tied.

“He wanted the judge to ‘do something, do something,’ and there’s nothing we can do until somebody files something. And it has to be an interested party,” Holmes said.

One of the beneficiaries requested a final settlement and distribution of the estate nearly a year after Knudsen’s death, probate court records show. It doesn’t appear she took all the necessary steps to intervene in the will.

As the third anniversary of Knudsen’s death approached, probate judge Lyman Holmes ordered Whalley to provide the register with addresses of Knudsen’s surviving relatives and file an inventory of the estate.

By the time Whalley wrote checks to the beneficiaries of the will, Jipson’s father and Margaret Deoca — a friend of Knudsen’s wife, Sue — had died and didn’t receive the $10,000 that was promised. Schevenieus died from a COVID-19 infection in December 2021, two months before the court suspended Whalley, according to his daughter, Karen.

She said her father, Dale Schevenieus, fought until the very end to have his close friend’s final wishes followed.

“He didn’t like anyone being bad to anyone else. He stood his ground,” Karen Schevenieus said.