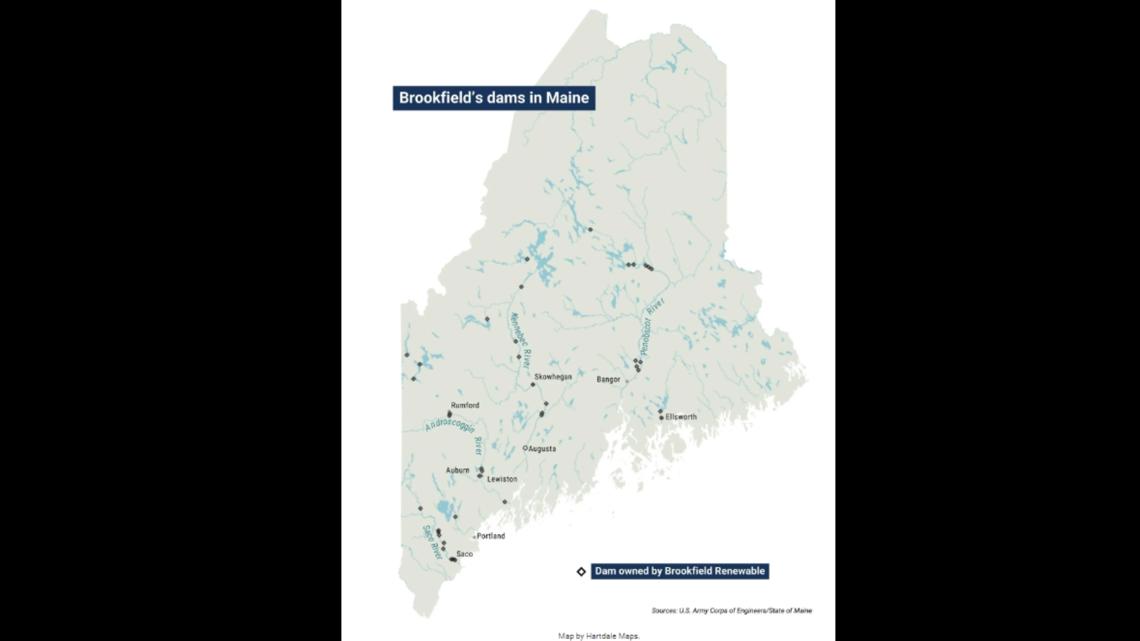

MAINE, USA — About a quarter of the electricity generated in Maine comes from hydropower, and most of that is produced by Brookfield Renewable, which owns dozens of dams in the state, from Saco to Millinocket.

In all, Brookfield generates about 87 percent of the hydropower and 21 percent of the wind power in Maine. It has also begun generating a growing amount of solar power, as well as some from biomass.

Brookfield’s parent company is a sprawling investment firm based in Canada that claims more than $925 billion in assets, with real estate, energy and infrastructure projects across the globe.

As Maine pushes toward its goal of running on 80 percent renewable energy by 2030, Brookfield appears poised to play an outsize role in the transition.

Yet aside from some high-profile conflicts over fish passage at its dams, Mainers rarely hear about this mega-corporation. Few realize the range of its influence in Maine — from the state’s largest dam to its oldest wind farm to one of its only battery storage systems.

A history of hydro

Brookfield started in Maine in 2002, when its corporate predecessor, Brascan Corp., bought the extensive hydropower network along the West Branch of the Penobscot River from the ragged remnants of Great Northern Paper.

Brascan had been founded over a century earlier as a Canadian company developing power in Brazil. By the 2000s it was owned by the Bronfman family — heir to the Seagram’s liquor fortune — and had developed a reputation for aggressively buying undervalued companies.

In a series of corporate shuffles, Brascan rebranded itself as Brookfield in 2005, and Brookfield consolidated its renewable energy assets. It took a big step toward dominating the Maine hydro market in 2012, when Brookfield Renewable bought a cluster of 19 dams from NextEra. The dams, in the Androscoggin, Kennebec, Presumpscot and Saco watersheds, were valued at about $760 million.

It was an era of frequent dam turnover. Paper mills were struggling and realized they could sell their dams for profit. Maine’s Restructuring Act, often referred to as electrical deregulation, required the state’s electrical utilities to sell their power-generating assets. And Federal Energy Regulatory Commission policy changes opened the wholesale electrical market.

Brookfield’s structure is famously abstruse, with hundreds of corporate entities, and has come under scrutiny for its business practices in a hostile bid for a Canada oil pipeline company, mortgage defaults in Los Angeles and the question of whether Qatar was involved in funding the corporation’s bailout of a Manhattan property owned by Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

The parent company is so massive that it’s the largest commercial property owner in Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, New York and Washington. It owns thousands of miles of railway worldwide, and has extensive investments in fossil fuels.

Most of the corporation’s renewable energy is owned by Brookfield Renewable; Brookfield Corporation has a 48 percent stake in that company. And the hydropower in Maine is managed by Brookfield Renewable US, a wholly owned subsidiary of Brookfield Renewable.

The solar and wind projects in Maine belong to several entities whose names indicate no connection to Brookfield but are owned by the corporation, such as Luminace and TerraForm.

Current operations

Brookfield’s dozens of dams are spread across Maine. They include the state’s largest — Wyman Dam and Harris Station on the upper Kennebec River — as well as dams impounding Chesuncook, Flagstaff and Moosehead lakes in the North Woods.

Brookfield also owns dams at the hearts of cities and towns, including Brunswick, Ellsworth, Lewiston, Rumford, Skowhegan, and Saco and Biddeford. The Middle River dam on western Maine’s Rapid River, famous for its trophy brook trout, is another owned by the corporation. In total, Brookfield’s dams have about 615 megawatts of generating capacity.

Through a different corporate structure, TerraForm, Brookfield has also been investing in Maine wind projects. It now owns the Bull Hill, Rollins and Stetson projects, as well as Maine’s oldest wind farm at Mars Hill. In all, its turbines have 220 megawatts of capacity.

Brookfield also owns Maine solar farms with nearly 100 megawatts of capacity, mostly through the state’s lucrative net energy billing program. This includes 56 megawatts owned by the Brookfield company Luminace (plus more under construction), and 57 megawatts owned by Standard Solar, which Brookfield purchased in 2022.

All of Brookfield’s energy — hydro, solar, wind and biomass — generates renewable energy certificates, or RECs, which turn megawatt hours of renewable energy into commodities.

Brookfield also has one of the only battery storage units in Maine, a 20-megawatt array of Tesla Megapacks along the West Branch of the Penobscot River near East Millinocket.

Maine’s renewables

Despite the many solar and wind projects built in Maine in recent years, hydropower is still the leading source of renewable energy in the state.

According to the Federal Energy Information Administration, renewable sources accounted for more than 62 percent of the 12.8 million megawatts hours of energy produced in Maine in 2022. Of that, hydropower comprised 3 million megawatt hours, or 38 percent of the renewable energy.

But power generated in Maine doesn’t stay here; it flows into the regional electric grid. Afton Vigue, a spokesperson for the Governor’s Energy Office, said 51 percent of the energy consumed in Maine is renewable, and the state is working toward its 80 percent goal. Vigue said this will reduce Mainers’ reliance on the natural gas that is still the largest source of electricity on the regional grid, and save them money.

But Vigue would not discuss Brookfield’s dominance of renewables in Maine. “Regarding Brookfield, our office neither oversees nor regularly tracks ownership of generation projects in Maine,” Vigue said. “We are unable to comment.”

Despite Brookfield’s outsize role, Maine Public Advocate Bill Harwood said his office “has no immediate concerns about Brookfield’s size.” Harwood noted the guardrails provided by the regional grid operator.

“ISO-NE (a regional transmission organization) works hard to make sure the New England wholesale electricity market is competitive,” Harwood said in an email. “And both ISO-NE and FERC carefully review the potential for market power or manipulation by sellers.”

Richard Silkman has watched Maine energy markets for decades, and recently retired after serving as CEO of the consulting firm Competitive Energy Services. (Some of the firm’s clients have contracts with Brookfield Renewable.) Silkman said Brookfield may be dominant in Maine but not on the regional power market.

“They are a big company, let’s face it. But they don’t have the ability to exercise market power, which is really the criteria that economists look at when we focus on concentration within the industry,” Silkman says.

“If Maine were isolated, and Maine could not import power from anywhere else, but had to use its own resources, then I think that degree of concentration could become troubling. But that’s not the case.”

Eliza Donoghue, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association, which counts Brookfield among its members, said other large renewable power companies in Maine include Onward Energy, with roughly 384 megawatts of capacity, and Competitive Power Ventures, with roughly 81 megawatts of capacity. Regarding Brookfield, Donoghue said it has done business in Maine for a while, and is diversifying its portfolio.

A green institution?

As one of the world’s largest renewable energy companies, Brookfield claims it is offering sustainable strategies for decarbonization. But it has faced significant pushback from environmentalists over fish passage at its Maine dams.

In 2021, the state recommended Brookfield remove four of its dams on the Kennebec River because of the harm they were causing endangered Atlantic salmon. Brookfield sued the state later that year, and Gov. Janet Mills eventually backed down. The conflict became a flashpoint during Mills’ reelection campaign. Her opponent, former governor Paul LePage, sided with the Sappi paper mill in Skowhegan, advocating for the status quo.

NOAA concluded that the dams could be compatible with salmon recovery if Brookfield dramatically improves fish passage. The company says it is pursuing fixes.

Last year, fish advocates criticized Brookfield over a malfunction at Ripogenus Dam that caused part of the West Branch of the Penobscot River to dry up for several hours; for the debris-clogged fishway at the Brunswick Dam; and for management of the Milford Dam on the Penobscot River.

In all, the relationship between Brookfield and environmentalists in Maine has been tense.

“They represent themselves as a green institution. It doesn’t quite jibe with what happens on the ground, and their fight to preserve the status quo,” said Dwayne Shaw, the Downeast Salmon Federation executive director who has battled with Brookfield to improve fish passage on Union River dams. “There’s a big difference between who they are and who they say they are.”

Brookfield argues otherwise, citing its staff expertise in fish passage, and its plans to improve fish passage on the Kennebec, which NOAA says could cost $100 million.

The future

In Maine, Brookfield typically operates by buying completed energy projects, not developing new initiatives. A spokesperson wouldn’t comment specifically on future plans.

“We are proud to play a role in supplying Maine with the power required to meet increasing electricity demand while also contributing to the state’s journey toward achieving net zero by 2040,” the company said in a statement.

Brookfield is steadily expanding its role as one of the biggest renewable energy companies in the world. But already its reach is so vast it can be hard to track.

When biomass plants in Jonesboro and West Enfield went belly up in 2022, Hartree Partners, which had been a creditor, assumed ownership in bankruptcy court. Hartree is owned by the hedge fund Oaktree Capital. The hedge fund is owned by Brookfield Asset Management.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.