AUGUSTA, Maine — Maine’s Native American tribes say they lost control over their own lands 40 years ago, and are hoping the Legislature will return at least some of the control they once had.

The tribes and the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee have been talking for more than a year about changes to the 40-year-old Maine Indian Land Claims Act. That law, passed by Congress and signed by President Jimmy Carter, ended the legal claim by the tribes to two-thirds of the land in Maine. The tribes were given money and allowed to buy hundreds of thousands of acres of land. But that same agreement restricted the amount of control the tribes could have over what happened on their land, which has been a source of resentment against state government ever since.

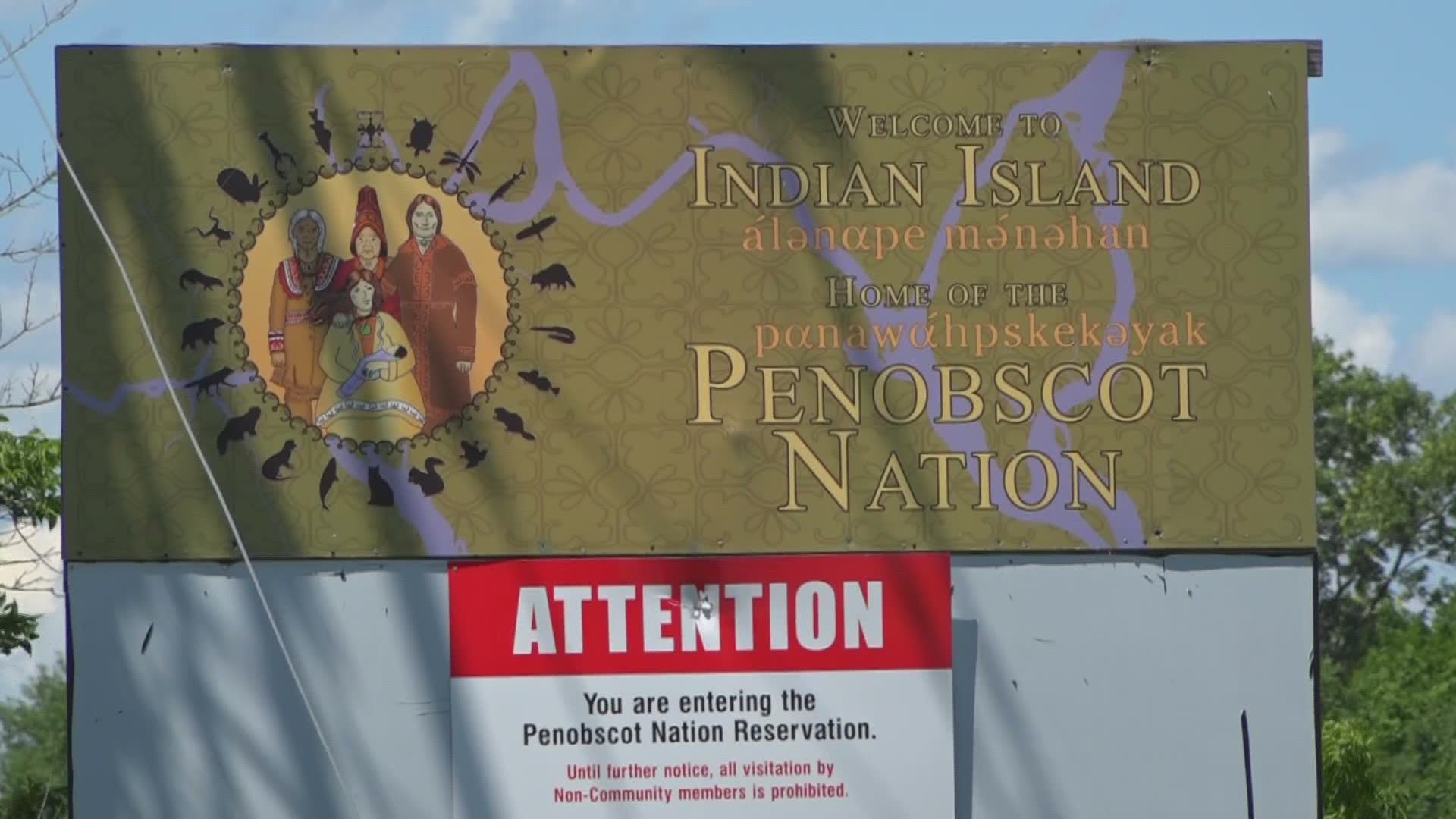

The four tribes—Penobscot, Passamaquoddies, Malisetts and Mic Macs—are now counting on lawmakers and the Governor to return much of the lost sovereignty, and Sen. Mike Carpenter, co-chair of the Judiciary Committee, says the time has come to do it.

“They need to regain their sovereignty, and I can’t put it more succinctly than that,” Carpenter said Wednesday. “The claims act of 1980 severely restricted-they would say stripped them, I disagree,-severely restricted their ability to govern their own affairs and we’re trying to rework that if you will.”

For most of the past year, a task force and members of the Judiciary Committee have worked on a bill to make those changes. It's complex because it involves identifying laws and practices that have existed for 40 years, and determining how those can and should be changed. The committee was closing in on an agreement in March when the Legislature abruptly adjourned because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now the committee is trying to finish the bill and get it to the full Legislature within a week, in the hope there will be a special session and a vote.

The discussions cover everything from enforcement of hunting and fishing rules to some criminal matters to property taxes among many issues. They also involve decisions about what laws should be handled only by tribal enforcement and courts, what ones should remain solely in state jurisdiction, and what might be shared.

“A tricky balance,” said Carpenter, who had to enforce the Land Claims Act when he was Maine Attorney General in the 1980s.

And while the changes would be significant, committee co-chair Rep. Donna Bailey (D-Saco) said Maine should be able to make them.

“I would look to the other 49 states, which have federally recognized Indian tribes and they operate under that system and have been able to do just fine. It does require more consultation and cooperation between the states and the tribes, but they all make it work and we can make it work in Maine as well.”

Tribal leaders say the issue is immensely important and gets to the foundation of who they are, and the ability to control their own destiny.

“As resources have grown the needs of the tribe have grown,” said Chief Kirk Francis of the Penobscot Nation, “and yet we’ve been handcuffed by this document four decades old and (we are) nowhere near the place we were then.”

Chief Francis said everything from expanding tribal land to economic development is held back by lack of sovereignty.

Darrell Newell, Vice-Chief of the Passamaqoddies at Indian Township, said he and many others feel it personally.

“We’re just striving to restore our sacred, inherent sovereign rights to make decisions for ourselves, to better our people for future generations.”