![Bus boycott 60th anniversary [video : 84624004]](http://bcdownload.gannett.edgesuite.net/tallahassee/41801896001/201605/1532/41801896001_4902580708001_4902534166001-vs.jpg?pubId=41801896001)

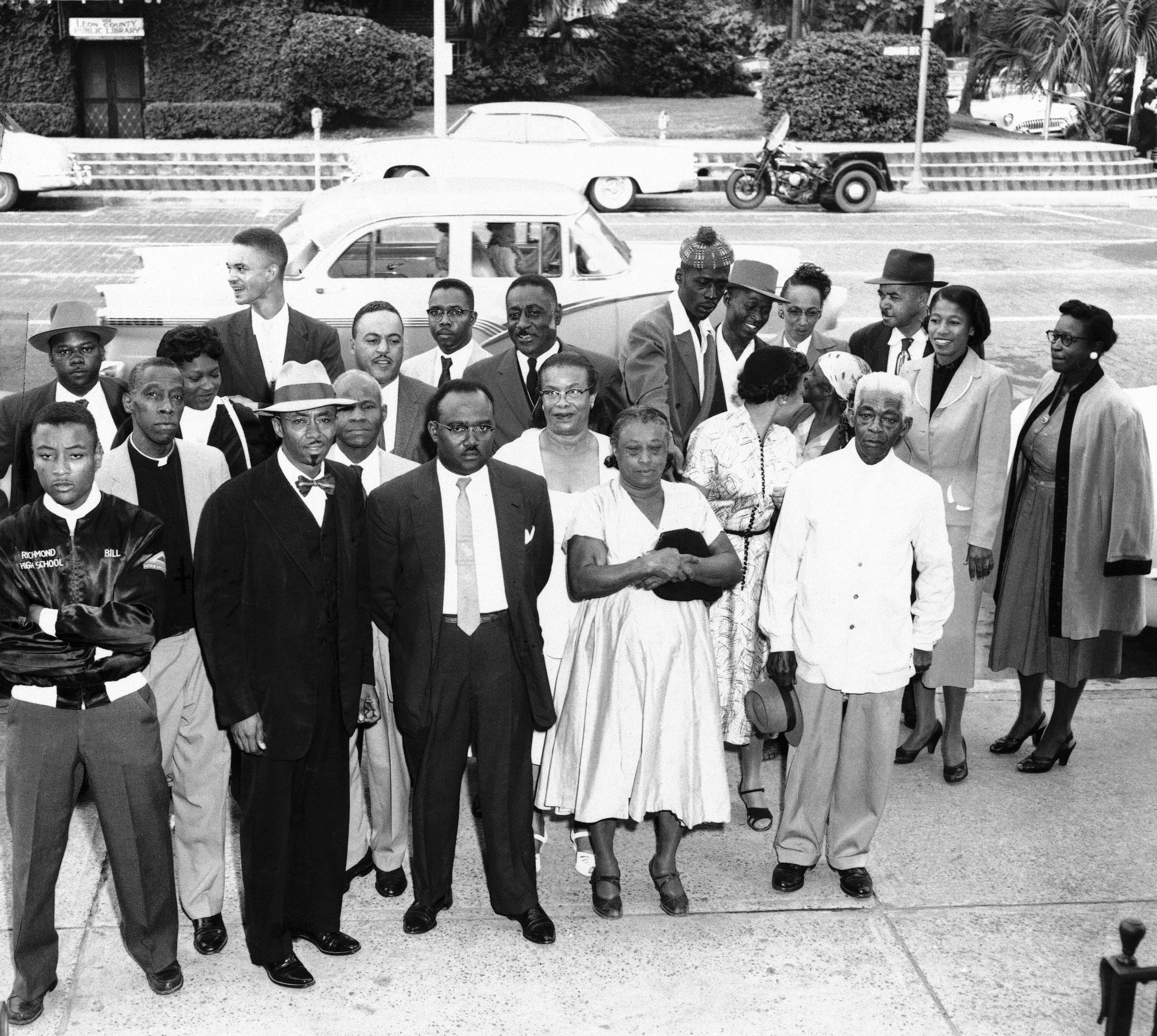

![C.K. Steelde [image : 84548108]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/4fad37721fa094f6ce986e60bdbf8d2ea7e2b8ec/c=0-61-3005-2629/local/-/media/2016/05/18/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635991764887764526-Boycott-defendants.jpg)

TALLAHASSEE — Sixty years later, it seems impossible to believe there was a time when blacks and whites were not allowed to sit together on Tallahassee city buses. It seems impossible to believe blacks were not allowed to sit in the front seats of a bus. Those seats were reserved for white people.

But in 1956, it was the law in Tallahassee, then still a small city of strict racial separation. The population was 38,000 — one-third black and confined to menial jobs or professional positions within the black community. Blacks could not eat in most white-owned restaurants. They couldn't shop at most white-owned stores; public water fountains were labeled for “whites only” and “colored only.”

On May 26, 1956, two Florida A&M students changed the course of history. Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson boarded a Tallahassee city bus and plopped down on a front bench beside a white woman.

![Rosa Parks marker unveiled in Montgomery, 60 years after bus boycott [oembed : 84754874] [oembed : 84754874]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

The bus driver ordered them to move to the back of the bus. When the two students refused, the driver drove to a nearby gas station and called the police. Jakes and Patterson were arrested and charged with placing themselves in a position to “incite a riot.”

Within days, the black community had inaugurated a bus boycott. For seven months, black residents — the bus company’s main customers — refused to ride city buses. The boycott attracted national attention. It led to the arrest of 26 people and two temporary shutdowns of the bus company.

And it changed Tallahassee forever.

![635991756383214010-Boycott-Wihemina-Jakes.jpeg [image : 84548102]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/2fbb071f98a3f9baceaec37d0d5a82fc8ef6b83c/c=0-47-194-213/local/-/media/2016/05/18/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635991756383214010-Boycott-Wihemina-Jakes.jpeg)

“It is impossible to overestimate the significance of the bus boycott in Tallahassee civil rights history,” said Glenda Rabby, author of The Pain And The Promise, the seminal book about the Tallahassee civil rights movement. “It was the first organized protest and successful challenge to racial segregation and discrimination in the city. The boycott helped to sow the seeds of discontent that would eventually flourish in a protest movement against the very foundation of Southern society: the unjust laws and customs designed to perpetuate and enforce racial inequality.”

![Alabama's Black Belt helped form Black Panther Party [oembed : 84754882] [oembed : 84754882]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

Tallahassee will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the boycott Thursday, with a daylong series of events. In the morning, there will be two panel discussions at FAMU, one of which will feature three participants in the boycott: Eddie Barrington, Henry Steele and Frederick Humphries.

The 1956 bus boycott was initiated by FAMU students. Jakes and Patterson were arrested on a Saturday; on Sunday night a cross was burned in the front yard of the home near campus where they rented rooms. On Monday morning, FAMU student body president Broadus Hartley called a meeting of the 2,300 students, who voted to boycott city buses.

Students spilled out of Lee Hall afterward just as a city bus was coming through campus. The students surrounded the bus and demanded passengers get off. Members of the football team lifted up one side of the bus and “literally shook people out of there,” said Humphries, the future FAMU president, then a junior chemistry major. “The student body was very upset.”

![635991756385086022-Boycott-Carrie-Patterson.jpeg [image : 84548090]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/537c9eaa55cddc1541923ca281c23bcac6d5efa1/c=0-72-300-328/local/-/media/2016/05/18/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635991756385086022-Boycott-Carrie-Patterson.jpeg)

But only a week remained in the school year, at a time when college students departed Tallahassee en masse during the summers. So the boycott could have fizzled.

But the next day, several dozen black pastors and businessmen met at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church to form the Inter-Civic Council to support the boycott. The group elected Bethel Baptist pastor C.K. Steele as ICC chairman.

![Black Panther Party's legacy of Black Power endures [oembed : 84754910] [oembed : 84754910]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

The next night, more than 500 black residents — including domestic workers, laborers, housewives, senior citizens, FAMU employees and state workers — met in support of the ICC and crafted three demands for city leaders: Bus seating should be first come, first served; all people should be treated courteously; and the bus company should hire black drivers..

It would be the ICC and the black adults of Tallahassee who carried the bus boycott.

![Remembering the 1956 Tallahassee Bus Boycott [gallery : 84666142]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/af467bfca30f94d89a06078611c0cebc36693b27/c=40-0-2661-2240/local/-/media/2016/05/20/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635993559056532637-JPG5b25alpsuu8fiftql4f.jpg)

“I was amazed and gratified by the big response. We saw people from all walks of life come together on the bus situation,” said retired pastor Henry Steele, second of C.K. Steele’s six children, who was 12 at the time. “Nobody complained it shouldn’t be done, or couldn’t be done.”

The boycott lasted seven months — which were tumultuous.

The city dropped charges against Jakes and Patterson, hoping to avoid a test case in the courts. Tallahassee Democrat editor Malcolm Johnson assembled a bi-racial committee in hopes of defusing the boycott; but the committee dissolved when 14 members of the ICC showed up to protest.

The Tallahassee City Commission tried to broker a deal with 15 “friendly” black leaders, including legendary FAMU football coach Jake Gaither — a gesture that earned contempt in the black community.

The city commission did ask the bus company to treat all customers courteously and hire black drivers. Seth Gaines, David Moore and Edgar Richardson were the first three black drivers hired.

But the city commission refused to endorse integrated seating on the buses. City leaders were convinced integrated seating on the buses would lead to school integration — which had been ordered by the Supreme Court two years before — and to chaos in Southern society.

Bus company revenues dropped precipitously as black residents refused to ride. On July 1, the buses stopped running entirely.

![635991756470574570-Henry-Steele-4-26-16.jpeg [image : 84548106]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/68fb338e2c85744fb88f6161bd4d1747d8a6b257/c=0-586-2448-2678/local/-/media/2016/05/18/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635991756470574570-Henry-Steele-4-26-16.jpeg)

“It was so good to see the solidarity of everyone,” Henry Steele said. “When the buses quit running it was unbelievable; it was a very good sign we were making inroads.”

To fill the transportation void, the ICC organized carpools, with 65 blacks carrying blacks to and from their jobs. City police responded by ticketing drivers for minor and imagined infractions: Steele was the first driver ticketed, charged with supposedly running a stop sign and speeding.

The city commission threatened to pass a law banning the carpools. Instead, the state attorney general ruled the carpools were violating state laws about cars for hire. In September, 21 drivers and the ICC were arrested and charged with violating the state law.

At their trial, all 22 parties were convicted by City Judge John Rudd and each sentenced to a $500 fine and 60 days in jail. Rudd suspended the jail sentences, but left the fines in place. ICC member Dan Speed, owner of a Frenchtown grocery store, paid the $11,000 in fines. Steele spent several years speaking around the nation to pay off the $11,000.

The convictions ended the carpools — and eventually the boycott. For a while, blacks walked to and from their jobs. On Dec. 23, 1956, the ICC voted to formally end the boycott.

In June, 1956, a federal court struck down segregated seating in a case brought by the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott. In November, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ruling: Integrated seating on buses was now the law of the land.

![635991756571819219-Boycott-drivers.jpeg [image : 84548092]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/5711e931ca35a7a790cfbd00b3be562439a6196f/c=0-65-2990-2621/local/-/media/2016/05/18/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635991756571819219-Boycott-drivers.jpeg)

Even so, the Tallahassee City Commission refused to rescind its ban on integrated seating. So the ICC voted to ride the buses in a “non-segregated manner.” Starting on Christmas Eve, Steele and other ICC members began riding the buses, sitting in the front “whites only” section. A Life magazine photographer captured the often-published photo of Steele and Bethel AME pastor H. McNeal Harris riding at the front.

Bus manager Charles Carter and nine bus drivers were arrested for allowing the integrated bus rides. The city announced it would revoke the then-private bus company’s charter. Steele and ICC responded by calling for a mass “integrated ride” on Dec. 27, 1956. But when 200 white youths showed with bats and rocks at the bus terminal at Park Avenue and Monroe Street, the protest was called off.

On New Year’s Eve, rocks were thrown through the windows of Steele’s home, next door to Bethel Baptist, and two weeks later gunshots were fired through the windows of Dan Speed’s grocery store. On Jan. 3, a cross was burned on the front lawn of Bethel Baptist Church.

The violence dismayed even the white community. The Tallahassee Democrat wrote an editorial condemning the cross-burning as a “shameful device unbecoming any citizen of a free country.” Gov. LeRoy Collins, a Tallahassee native, stepped in to head off further violence; on Jan. 1, he suspended the bus service.

On Jan. 9, the city commission offered its solution: assigned seating on city buses. Drivers were ordered to assign seats to every rider based on “weight distribution,” “health and safety,” and “peace, tranquility and good order.” Though the policy was designed to still separate bus riders based on race, it made no mention of segregated seating.

The policy satisfied Collins, who lifted the ban on the buses. But blacks continued their unofficial boycott, and the buses operated half full for a week.

On Jan. 19, 1957, the ICC tried a new tactic: Three black FAMU students and three white FSU students boarded a bus and took their assigned seats. Once the bus began moving, one white student, Joe Spagna, jumped up and traded seats with one of the black students, creating two interracial groups of riders. When Spagna refused to return to his seat, the driver drove the bus to the police station, where Spagna and his two black companions, Leonard Speed and Johnny Herndon, were arrested.

Judge John Rudd found all three guilty, sentencing each to 60 days in jail and a $500 fine. The case was appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case. In June 1958, Herndon and Speed served 15 days of their sentences, before Rudd released them. Spagna, the only white person arrested during the boycott, had already graduated and left Tallahassee.

![635991756937017560-Boycott-Steele-Harris.jpeg [image : 84548100]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/64984dafd9fe8f96eefa92e882df9540a54efa6f/c=240-0-5760-4718/local/-/media/2016/05/18/Tallahassee/Tallahassee/635991756937017560-Boycott-Steele-Harris.jpeg)

Under pressure from a Collins-appointed bi-racial committee, the bus company was allowed to gradually rescind its assigned seating program. Blacks began returning to the buses. Though the assigned seating ordinance was never officially repealed, it was considered wiped from the books when the bus company was sold to the city in 1974.

The Tallahassee boycott started five months after the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala. (1955-56), which was a watershed event of the civil rights movement and catapulted its leader, Martin Luther King Jr., to national fame. There also were bus boycotts in Atlanta, Miami, Tampa, Baton Rouge, La., and Columbia, S.C.

But Tallahassee’s boycott had made a mark. On May 26, 1957, the ICC celebrated the one-year anniversary of the bus boycott, with a rally that drew King to Tallahassee to speak.

“Tallahassee’s boycott was sustained without the considerable outside financial and moral support that poured into the more famous boycott in Montgomery,” Rabby said. “It proved that local blacks in other Southern communities could sustain an indigenous and ongoing protest movement against segregation.”

The bus boycott kick-started Tallahassee’s civil rights movement.

In 1957, Rev. K.S. Dupont became the first black since Reconstruction to run for the city commission; in 1971, James Ford became the first black elected to the city commission. In 1960, FAMU students boycotted segregated lunch counters, gaining national attention for a “jail-in,” in which Patricia Stephens Due and 10 others stayed in jail for 49 days rather than pay their fines. In 1963, FAMU and FSU students picketed Tallahassee’s racially segregated theaters.

Today, blacks and whites sit anywhere they wish on city-owned StarMetro buses. Of StarMetro’s 107 bus drivers, 94 are black. Tallahassee, whose 186,000 population is still one third black, has had black mayors, black city commissioners, a black city manager, a black chief of police and hundreds of public positions filled by blacks.

A new generation has never known a segregated Tallahassee.

“I thought the boycott was the greatest move we ever made and was necessary to get rid of an evil that had no business being there,” said Eddie Barrington, 96, a black barber and florist who was assistant secretary of the ICC. “The boycott was very important to Tallahassee and Tallahassee hasn’t been the same since. It made a mighty, mighty difference.”